This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

An eclectic mix of truly special performances

Stunning stereo XR-remastered sound quality that just has to be heard!

Following a generally favourable response to our release in 2009 of Felix Slatkin's Delius, Saint-Saëns and Ibert recordings we decided to delve deeper into the back catalogue and, thanks to the hard work of Edward Johnson, put together the present double-CD-length release, which aims to cover even more eclectically the kind of music Slatkin was recording in the mid to late 1950s.

The musical scope here in without doubt broad, and yet despite bringing together the recordings from four very different LP releases it seems to work well as a single collection. Dohnanyi's Variations on a Nursery Theme is sheer brilliance from start to finish, and the performance here captures brilliantly the multi-faceted nature of this remarkable work, based on the tune Twinkle, twinkle little star (or, if you prefer, Ah, vous dirai-je, Maman).

In some ways the piece sets the tone for the rest of this album as it moves from one musical style to another, with Dohnanyi encompassing (as the notes state) the musical styles of "nearly every composer his audience of 1914 would have been familiar with". Victor Aller's performance sparkles and, yes, twinkles throughout, and is really not to be missed.

The Khachaturian is altogether a weightier work - a proper piano concerto to Dohnanyi's piece labeled "for orchestra and piano concertante" - and Pennario delivers it well. He had taken it into his repertoire in the mid-50s following the death of his great friend William Kapell, who had given the US premiere in 1943 and later recorded the work with Koussevitzky. Pennario's performances at the time work huge critical acclaim.

Britten's much-loved Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra brings us back, in a sense, to the world of the Dohnanyi - a set of variations on a theme, in this case by Purcell, which takes the listener on a rich and varied musical journey, with humour and grandeur. Slatkin's brilliant orchestra rises to the challenge, and the recording captures the fine brilliance of the performance with astonishing clarity, thanks in no small measure to the early use of stereo to steer us around the orchestra's instrumental sections.

Disc two brings greater variations, if you like. Taken from two LPs, the first entitled "The Cello Galaxy", the second simply "Percussion!", we find two often-neglected sections of Slatkin's orchestra brought to centre stage. Villa-Lobos' Bachianas Brasileiras are scored for eight celli and are among his most popular and successful works. The addition of a solo soprano to the fifth adds a further dimension to these brilliantly scored works. Meanwhile the Bach arrangement calls for a cello 'orchestra' - in this recording no less than 26 cellists were arranged in what the sleevenotes described as "a shallow semi-circular row... in four groups with eight players in the first and six players in each of the others". It makes for a quite uniquely rich and sonorous interpretation of one of Bach's great works.

In the works for percussion we slip back to the mono era - which is something of a shame as this music is perhaps particularly suited to a stereophonic treatment. Nevertheless again the performances and recordings are more than worthwhile. A newcomer to Carlos Chavez's Toccata might baulk at a three movement work for percussion alone, but fear not - it's a captivating piece of music brilliantly played. Despite the apparent absence of melody and harmony (though of course these are present in instruments such as the glockenspiel, xylophone, chimes and - to a lesser extent - tuned drums), somehow the composer manages to weave together a convincing and expressive musical narrative.

Milhaud, on the other hand, presents the percussionist with an orchestral backdrop, which provides the main musical ideas of the piece and allows the soloist the scope for exotic coloration. Both of these 1954 recordings have had Ambient Stereo treatment to add a sense of space around the instruments whilst maintaining the central, mono imagery of the originals. It's a testament to the excellence of performers and recordings that both capture and hold the imagination of the listener throughout.

Working from LPs in generally immaculate condition I was able to produce some quite excellent remastered recordings using Pristine's acclaimed XR processing. However, something remained to be addressed. Reviews of the first release tended to dwell, momentarily at least, on the exceptionally dry acoustic of the sound - writing at MusicWeb International, Jonathan Woolf complained that despite my efforts with XR remastering, "it seems not to have been able to ameliorate the chilly acoustic", whilst Lewis Foreman, writing for the Delius Society Review, also noted: "The actual orchestral playing is very good, but the enterprise is compromised to some degree by the acoustic which has no natural resonance to it; it’s just flat." (It's perhaps worth being reminded at this point that these are both highly experienced and esteemed critics, well-used to the drier acoustics of many older recordings.)

The reason for this is almost certainly the same thing which dogged a number of the present recordings - the recording location, Samuel Goldwyn Studios Stage Seven in Hollywood, CA. This is in every sense not a concert hall, and from all the evidence here it sounds as if it was designed to be particularly acoustically dead. This is not flattering to a musical performance, though it certainly has its uses in the realm of film sound production, even more so now that it would have done in the 1950s.

A dead, dry sound can be processed in such a way as to appear to "be" somewhere else. Traditionally this would have been done using various echo chambers, reverberation plates and equalisation, much as I learned when first working on radio drama productions at the BBC, where it's highly desireable to have a single studio space which can be made to sound like almost any generic venue a dramatist wants it to be - outdoors, in a small or large room, a cavern or, indeed, some alien world.

What we can also do now, however, is effectively "relocate" an acoustically dry recording to a specific venue, using a process called "convolution reverberation". An impulse recording, made in a particular place, can be used as a precise multi-dimensional acoustic model to recreate the echoes and reverberant acoustic of that location in another recording - and if it's a bone-dry echo-free recording, it can relocate that recording in an astoundingly-convincing manner. If we input the dry sound of the Concert Arts Orchestra to this system, it is possible to hear that Orchestra as if one was sitting hearing that same performance from the concert stage, whilst of course sitting in the best seat in the house, at any number of the world's finest concert halls and auditoriums.

It's a tremendously powerful and sonically seductive tool - and one of classical recordings dirty secrets is that digital reverberation gets used far more than is ever admitted on modern recordings - but should one really consider applying it to these 1950s recordings? I have to admit I was exceptionally wary - until I heard the result for myself.

I discussed these thoughts in an e-mail exchange with Felix Slatkin's son, the cellist Frederick Zlotkin, during the preparation of this release, explaining my aims, hopes and intentions. He commented thus, and I took his words very much into account:

"Re. the "dry" acoustic, I would only ask that any reverb be added quite "gently." As a big fan of 78s and early LPs I enjoy the simple fact that these recordings really tell you what the musicians actually sounded like, without "hiding" in the echo. In the case of the Hollywood crew, you had some of the greatest musicians of all time, and their playing stands up to this kind of scrutiny magnificently. I know you will be careful."

My aim therefore was clear - to retain the finest details of the dry recording whlst give it just enough acoustic "air" to allow it to breathe. I cycled through literally dozens of combinations of concert venues and possible microphone placements until I found the locations I felt were most sympathetic to the recordings, and then used their acoustics as sparingly and sympathetically as possible. Curiously, although all three Stage Seven recordings seemed most "at home" in the concert halls of Santa Cecllia, Rome, the Dohnanyi and Britten seemed immediately best-suited to the medium-sized Sala Sinopoli, whilst a different microphone placement used for the Khachaturian recording made it more comfortable in the larger (and thus slightly longer in its reverberance) Sala Santa Cecilia.

Learning about this kind of manipulation can be emotive for many listeners. Many do not like the sound of any artificial reverberation or echo, and for very good reason. Even the very best synthetically-generated acoustic tends to have an artificial sound to it., and outside of the popular music sphere can often sound very inappropriate. This, however, is my first foray into this relatively new technique, and it's only recently that we have acquired the raw computing power to be able to use this kind of processing in everyday applications.

As with our use of Ambient Stereo and XR remastering techniques, a great deal of careful and critical listening has taken place before the decision was made to go ahead with its use here. These are particular recordings in case, and it's not a technique which needs regular use with historic recordings. But I do believe it will both address the acoustic shortcomings picked up on by reviewers of our earlier release and find a sympathetic response in listeners more generally.

My own response to the technique, once fully optimised for these particular recordings, was one of utter astonishment and delight. For the first time in 25 years of listening to these kind of effects in studio environments I heard something which was truly convincing - and which in myriad subtle ways managed to enhance the recording without adding any sense of artificiality. To me it seemed to sit perfectly alongside my aims in XR remastering of overcoming genuine shortcomings in older recordings using the most highly advanced modern digital remastering methods in as sympathetic a way possible to the originals.

Andrew Rose

Disc One - Stereo recordings

-

DOHNANYI Variations on a Nursery Theme, Op.25

Victor Aller, piano

recorded 29th September 1956

-

KHACHATURIAN Piano Concerto in D flat

Leonard Pennario, piano

Recorded 5-6 October, 1956

-

BRITTEN Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra, Op. 34

Recorded 18 & 20 August 1956

The Concert Arts Symphony Orchestra

conducted by Felix Slatkin

Recorded at Samuel Goldwyn Studios, Stage 7

1 & 3 issued as Capitol Stereo LP SP8373

2 issued as Capitol Stereo LP SP8349

Disc Two - Stereo & Mono recordings

- VILLA-LOBOS Bachianas Brasileiras No. 1, W.246

- *VILLA-LOBOS Bachianas Brasileiras No. 5, W.389-391

-

BACH Prelude & Fugue No. 8 in E flat minor (arr. Villa-Lobos)

*Marni Nixon, soprano

Concert Arts Cello Ensemble

conducted by Felix Slatkin

Recorded 10-11 January 1959, Capitol Tower, Studio B

Issued as Capitol Stereo LP SP8484

- CHAVEZ Toccata for Percussion

-

*MILHAUD Concerto for Percussion and Small Orchestra

*Hal Reese, percussion

Concert Arts Orchestra & Percussionists

conducted by Felix Slatkin

Mono recordings presented in Ambient Stereo, made at Capitol Records, Melrose Studio

4: Recorded 17 October 1954

5: Recorded 10 January 1955

Issued as Capitol Mono LP P-8299

"Near the end of the month I was informed about a release of a CD, containing music by Delius that was conducted by my father. In his fledgling days as a conductor, he recorded several albums with a pick-up orchestra called the Concert Arts Orchestra. These performances stem from the early fifties and back then had a devoted following in the record-buying community. A company called Pristine Classics [sic], based out of the UK [sic], re-mastered a couple of my Dad’s recordings and I have to say that they have done an incredible job. Hopefully, they will get around to issuing the remaining albums...."

Leonard Slatkin, "Notes" blog, November 2009

Transfers by Edward Johnson from his private collection

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, March 2010

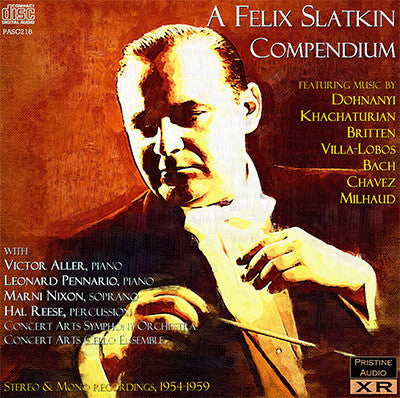

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Felix Slatkin, courtesy of Frederick Zlotkin

Total duration: 2hr 19:10

Fanfare Review

Altogether a gem of a set

Felix Slatkin was one of the most versatile musicians of the 1950s, as a concertmaster on the Los Angeles studio scene (including on Frank Sinatra’s Capitol recordings), first violin of the fabled Hollywood String Quartet, and conductor of the Concert Arts and Hollywood Bowl orchestras.

This enterprising set restores to circulation some Concert Arts classics recorded for Capitol in the later 1950s, featuring both the full orchestra and ensembles drawn from it. Its sonic character is very distinctive: that “Hollywood” sound, with its shimmering, glamorous patina. The strings’ style is freely expressive, tonally rich, with more (and unselfconscious) use of expressive portamento than was common in the classical world at that time. Winds are full-toned and vibrant, vocal in phrasing with liberal use of expressive vibrato. Rhythmic style is light in touch, crisply pointed.

The Britten (recorded 1956) makes a marvelous showcase for the stellar quality of every department of the orchestra. Perhaps surprisingly, Britten comes off with less of a “foreign accent” here than in other non-British versions from around this time: van Beinum/Concertgebouw (Decca, 1953) or Ančerl/Czech Philharmonic (Supraphon, 1958); of course, the presence of a British orchestra in itself guarantees nothing—Giulini (Philharmonia/EMI, 1962) makes the music sound like Bruckner! Slatkin’s Californians have much more in common with the natural idiomaticness of Boult (Pye/Nixa, 1956, but the Concert Arts play rings around the lean, mean London Philharmonic) and Britten himself (London Symphony Orchestra/Decca, 1963). The performance is admirably faithful to Britten’s meticulously detailed markings; more important, it radiates spontaneity and enjoyment.

The performance of the Dohnányi pits Victor Aller’s straight, rather deadpan playing against Slatkin’s richly characterful accompaniment—an effective way to play this once-popular, now rarely heard score, and the opposite of the contemporaneous version from Katchen/Boult (with a much more characterful soloist, and well conducted, but again the LPO is no match for the Hollywood orchestra).

The Khachaturian is a real period piece—glorified Soviet poster art, really, in its mélange of folk elements with generic urban modernism (Prokofievian bitonality, but without his originality); unsubtle, rambling, but effective in its way. Leonard Pennario’s crisp, debonair treatment makes the best possible case for it, and Slatkin provides luxury support—gorgeous wind solos in the slow movement, including the silkiest bass clarinet you’ll ever hear. The work enjoyed improbable Western popularity in the postwar period, with recordings from Kapell/Koussevitsky (steely and intense); Levant/Mitropoulos (bullish, hard-bitten); and Lympany/Fistoulari (softer-edged, more musical—if that really qualifies as a virtue in this context—but the only one to include the called-for wailing flexatone in the slow movement).

Of the shorter pieces on disc 2, the cello ensemble plays Villa-Lobos with immense panache and stylistic empathy. Marni Nixon (better known for her work in musical soundtracks) would alone be worth the price of the set: She is perfection, with a bell-like clarity tempered by a hint of smokiness; stunning agility; and dead-center intonation of your wildest dreams—once heard, never forgotten. The Bach arrangement is the E♭-Minor from WTC, Book 1, but transposed to D Minor (prelude) and C Minor (fugue), respectively. Whatever your feelings about such arrangements (including in this case the curious addition by Villa-Lobos of a few extra pedal notes), the performance has an all-out intensity and overwhelming richness that are impossible to resist. As for the Chavez Toccata, well, no doubt it’s gripping stuff for percussionists … . But the Milhaud is fun, with its weird little orchestra of flutes and clarinets, solo trumpet and trombone, and strings.

The recording is clear, though in a very dry studio acoustic. Transfers are excellent as usual from this source, and the music-making so vividly communicative that any sonic limitations are quickly forgotten. Altogether a gem of a set.

Boyd Pomeroy

This article originally appeared in Issue 34:2 (Nov/Dec 2010) of Fanfare Magazine.