This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Cast Listing

- Cover Art

Rare world première recording of Rimsky-Korsakov's Tsar Saltan

"I enjoyed Tsar Saltan every bit as much as Sadko, perhaps even more ...

Anyone who settles down prepared for a long fairy tale should find no longueurs, and hours of enchantment"

- The Gramophone

This recording had been awaiting transfer for some time when it popped up on the wish list of the associate editor of one of America's major classical review magazines in an e-mail I received a few weeks ago, together with a very good reason to tackle it: "The c. 1957 recording of Rimsky-Korsakov's Tale of Tsar Saltan with the Zagreb Opera. I've never even heard it, but it was universally praised upon its original release, and remains one of only two recordings ever made". The other recording, a Soviet Melodiya production with the Bolshoi Theatre, was made in 1958, two years after the present Zagreb recording - and a copy of this helped me with the track splitting of this release. Although the Philips LPs from which this transfer was taken were in excellent condition (some occasional swish notwithstanding), the sound of the original was dim and murky in the extreme. So it came as a very pleasant surprise to me to discover that, hiding in the murk, there was a very nicely recorded opera trying to get out. That's not to suggest it's without criticism, technically: a boxy bass lacks real depth despite my best efforts; wow and flutter was persistent throughout, though has been largely cured here; end of side distortion was a problem to be largely overcome. It's certainly a product of its age - and yet there's a good balance between the musicians and singers, and the latter come across very well indeed, with diction crisp, clear and very well defined.

The Tale of Tsar Saltan may be one of the less well known of operas - it was certainly new to me - except for the appearance in the third act of the Flight of the Bumblebee, a test for any orchestra. The Zagreb Opera Orchestra tackles it with confident aplomb. Meanwhile the singers do a sterling job. This first CD and digital issue of this recording is surely long overdue.

Andrew Rose

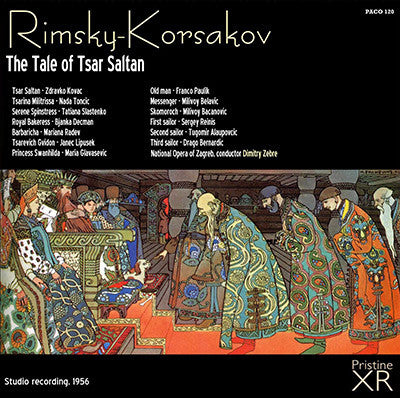

RIMSKY-KORSAKOV The Tale of Tsar Saltan

CAST

Tsar Saltan - Zdravko Kovac

Tsarina Militrissa - Nada Toncic

Serene Spinstress - Tatiana Slastenko

Royal Bakeress - Bjanka Decman

Barbaricha - Mariana Radev

Tsarevich Gvidon - Janec Lipusek

Princess Swanhilda - Maria Glavasevic

Old man - Franco Paulik

Messenger - Milivoy Belavic

Skomoroch - Milivoy Bacanovic

First sailor - Sergey Reinis

Second sailor - Tugomir Alaupovcic

Third sailor - Drago Bernardic

Zagreb National Opera Chorus and Orchestra

Dimitry Zebre, conductor

Recorded 18 November, 1956

Zagreb, Yugoslavia

Produced/engineered by:

Negri / Simek / Buczynski

Released as Philips LPs A 02014-16 L

Fanfare Reviews

My preference is unequivocally for this Pristine version, and I accordingly give it my enthusiastic endorsement

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, I continue to maintain, is one of the great opera composers, and those who have explored his oeuvre have generally considered Tale of the Tsar Saltan (Skazka o tsare Saltane) to be at or near the top among his operatic creations. A few orchestral episodes from the work are well known, and one, the ubiquitous “Flight of the Bumblebee,” figures as a popular showpiece or encore in various arrangements. Aside from two German-language live performances not intended for commercial release, however, only two complete recordings have ever been made of this opera, both of them dating from the 1950s. Melodiya recorded it in 1958 but never did a stereo remake, and although the work is in the repertoire of the Mariinsky Theater, it was not included in the series of Russian operas this company recorded for Philips in the 1990s. Since then, the Mariinsky’s own proprietary label has ignored my pleas to rectify this obvious gap in the discography of Russian opera and has chosen instead to focus on works already well represented in the catalog. Both of the earlier mono recordings, at least, have now been reissued. The Pristine release reviewed here was recorded by Philips in 1956 with a mostly Yugoslav cast and is dubbed from LPs. Melodiya reissued its one and only recording last year (see James Altena’s review in 38:2), but there were previous reissues on the Aquarius and Monopole labels. The latter is to be avoided, however, as it suffers from botched editing, with episodes appearing out of order in the Prologue.

Like so many Russian operas, Tsar Saltan is based on a work by Pushkin. The 1831 Pushkin tale falls into the category of invented or imitation folklore (a skazka is a folk or fairy tale). The story follows a familiar pattern, but with entertaining details. In the city of Tmutarakan, by the Black Sea, a virtuous maiden, Militrisa, is mistreated by her two wicked older sisters and their confidant, the spiteful old matchmaker Babarikha. Tsar Saltan overhears the sisters discussing what they would do if they were the tsarina. One would prepare a sumptuous feast for the entire realm, another would weave a fine linen cloth, but Militrisa would bear a mighty hero ( bogatyr) for a son. The Tsar chooses Militrisa as his bride, while the other sisters are accorded the roles to which they aspired of cook and weaver. While Saltan is away at war, Militrisa fulfils her promise to bear a son, but Babarikha and the jealous sisters, substituting their own message for Militrisa’s, inform the Tsar that she has given birth not to a son but to an “unidentified little beast.” The Tsar sends orders that Militrisa and her child are to be sealed in a barrel and thrown into the sea. (In Pushkin, it is not Saltan who is responsible for this order but rather Babarikha and the wicked sisters, who have substituted their own message for the Tsar’s command to take no action until he returns.) Mother and son eventually wash ashore on the desert island of Buian and break out of the barrel. Gvidon, by this time fully grown, saves a swan who is being pursued by a bird of prey, killing the attacker. The swan turns out to be an enchanted princess and the bird of prey a sorcerer. With the latter’s demise, a magnificent city appears on the island, and its inhabitants acclaim Gvidon as their ruler. When he tells the swan of his desire to see his father, she helps him to turn into a bumblebee and tells him to follow some merchant ships bound for Tmutarakan. Upon arriving, the traveling merchants are invited to the Tsar’s court. They recount the wonders they have seen on the formerly deserted island of Buian, of the magnificent city, of a squirrel who cracks golden nuts with emerald kernels, of the 33 bogatyri (mighty warriors) patrolling the island, and of Prince Gvidon who rules there. Saltan expresses a desire to visit the island and see these wonders for himself. When the wicked sisters and Babarikha attempt to dissuade him, they are each stung by the bumblebee. Back on Buian, Gvidon tells the swan of his desire to find the beautiful princess of whom he has dreamed. She is promptly transformed into that princess. The Tsar arrives with his ships and is reunited with his wife and son. In his joy he forgives the wicked sisters, while Babarikha, whom the sisters blame for their transgressions, makes herself scarce. The opera ends with general rejoicing.

Rimsky’s colorful score is saturated with the idioms of Russian folk music, and he adapted many actual folk melodies for use in the opera. Comparison between the Melodiya’s echt-Russian recording and Pristine’s Yugoslav one pits an inspired, thoroughly idiomatic performance against a dutiful, competent one that is unidiomatic in Russian pronunciation. There is a widespread impression that if you need someone to sing in Russian, any old Slav will do, but with the apparent exception of Bulgarians, members of non-Russian Slavic nationalities are no more qualified by birth to sing Russian than Italians are to sing French. Much of what I hear from the Pristine cast has a definite non-Russian accent, and I do not hear the precise enunciation and responsiveness to the text that the Russian one delivers superbly. Rimsky’s vocal writing is closely tied to the rhythm and flow of the Russian language, and inaccurate pronunciation undermines the effect. The leadership of the Zagreb conductor Dimitry Zebre often seems cautious and earthbound compared to the vigor, urgency, and rhythmic liveliness of Melodiya’s Vasily Nebolsin. Zebre’s tempos tend to be slower, sometimes even plodding. Too often he allows tension to slacken, and he adds nearly nine minutes to Nebolsin’s overall timing.

For the most part, good-quality voices are to be heard on the Pristine release, but the Russian cast performs with greater character and dramatic involvement. In the title role, Zdravko Kovač deploys a smooth, well-rounded bass voice of ample size and weight, but with his generalized delivery, he lacks the imposing presence and commanding authority of the legendary Ivan Petrov on Melodiya. He consistently mispronounces the Russian hard “l.” As Militrisa, Nada Tončić lacks the vocal fullness and even production of Melodiya’s Evgeniya Smolenskaya. She can sometimes be a bit hooty and display a weakness at the lower end, and Smolenskaya sings with greater passion and involvement. Melodiya’s Prince Gvidon, Vladimir Ivanovsky, has the larger, more heroic voice and stronger high notes, but the lyricism of Pristine’s Janec Lipusek is a viable alternative to Ivanovsky’s declamatory approach, or would be except for the issue of pronunciation—Lipusek’s Russian sometimes sounds to me more like Czech. (From his name, he could be Czech or Slovak; I haven’t been able to find out much about him online.) Maria Glavašević, the Swan Princess on Pristine, has a sweeter and steadier tone than Melodiya’s Galina Oleinichenko and less of a tendency toward shrillness in high notes. Her love duet with Gvidon in act IV, scene 1 is more tender than its Melodiya counterpart. With Marijana Radev’s Babarikha (Pristine), we get a good mezzo voice, but the acrid tone of Evgeniya Verbitskaya (Melodiya) is surely appropriate for an evil old crone who, when in act I the chorus of nursemaids is singing a lullaby to the newborn prince, interjects, “Baiu bai, poskoree umirai!” (Rock-a-bye, quickly die!). Both sets of sisters are very good vocally, but in their most extended sequence, in the Prologue, the Pristine pair is somewhat undercut by conductor Zebre’s lethargic tempo. Mark Reshetin, Melodiya’s Jester is more droll than his straightforward Zagreb counterpart. Pavel Chekin, the Old Grandfather on Melodiya, sounds like the senior citizen he is supposed to be while still singing proficiently; Franco Paulik, on Pristine, often sounds like a much younger man. More effective characterization as well as solid vocalism is also heard from Melodiya’s Messenger, Aleksei Ivanov. He sounds a bit drunk, as he is supposed to be. The Bolshoi Orchestra plays with spirit but is occasionally short on precision in the brass. The unheralded Zagreb orchestra, at more sedate tempos, is sometimes more precise in execution. The Bolshoi Chorus sings with greater verve and incisiveness.

As for sound quality, Melodiya’s recording is brighter, clearer, and more vivid, offering superior orchestral detail. The remastering engineers have done a good job in taming the shrillness and glare characteristic of older Melodiya recordings. Pristine’s sound is more blended, with more weight in the bass but a comparatively backward balancing of the orchestra. Overall, I prefer the Melodiya sound. Melodiya is superior, too, in presentation and packaging, although both releases make use of Ivan Bilibin’s wonderful illustrations for the Pushkin work. Neither release includes a libretto, but Melodiya offers a much larger number of tracks with a detailed track listing that helps one figure out who is singing in the absence of the text. (I secured a Russian-only libretto from a library, but James Altena has discovered a link that provides the text in Cyrillic, Russian transliteration, and English: aquarius-classic.ru/album?aid=188& ver=eng.) Melodiya also provides a more ample program note and a more detailed synopsis. The track numbers and timings on Pristine’s rear insert are very small and faint, and difficult for my 70-year-old eyes to read. More seriously, many of the tracks on the second CD are mislabeled. I am informed that this problem is being corrected.

Lovers of Russian opera should have a recording of Tsar Saltan. Pristine’s offers some rewards, but Melodiya’s is a clear first choice.

Daniel Morrison

This article originally appeared in Issue 39:2 (Nov/Dec 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.

My colleague Dan Morrison reviewed this set in the previous issue (39:2), and I urge anyone reading this review to have his superb discussion on hand when reading my own comments, as this provides a good example of how two critics not only can hear the same things, but even hear many of them in much the same way, and yet reach differing assessments.

As Dan has ably discussed Rimsky-Korsakov’s compositional idiom and aesthetic objectives in his review, and supplied a detailed synopsis of the plot, I will proceed directly to my own evaluation of the merits of this recording in comparison to the recently released rival on Melodiya that I reviewed back in 38:2. Possibly the most crucial point of difference between us concerns the relative importance we attach to correctness of pronunciation and clarity of diction. The 1958 Melodiya set has the inherent advantage of an all-Russian cast, whereas this recording, originally made by Philips in 1956, was made in then Yugoslavia (now Croatia) with a primarily Croatian cast. Dan pinpoints various flaws in the pronunciation of Russian by the singers in the Philips set, and his professional expertise here (he has a Ph.D. in Russian history and is fluent in the language) is a major factor in his preference for the Melodiya set. By contrast, I do not know Russian and so do not share his degree of sensitivity to the issue here; even when following along with a transliterated libretto (online at aquarius-classic.ru/album?aid=188& ver=eng), I cannot spot any errors to a degree that I would find disturbing. Similarly, while the Melodiya singers do have greater clarity of diction, I find that of the Philips singers quite satisfactory, and not all indecipherable or blurred à la Joan Sutherland (who was rightly considered a phenomenal artist despite her serious deficiency in that respect). Consequently, collectors considering acquisition of either (or both) of these recordings should consider how much weight they attach to such factors in determining a preference here.

Instead, I focus primarily upon various qualities of the singers’ voices and interpretations. Unlike Dan I find myself to have an overall preference for this Pristine Audio set, though again our differences result largely from divergent reactions to common factors. The two pairs of elder sisters, the Cook and Weaver, are excellent in both recordings, though I have a slight preference for the Philips pair because the voices of the two singers have more distinctly contrasted and sweeter timbres that make for a superior blend of beauty in their concerted passages. In the key role of the youngest sister Militrisa, however, I find that Nada Tončić clearly takes the palm over Evgenia Smolenskaya for Melodiya for beauty of tone, security of technique, and fitness of interpretation, the latter being a decided disappointment in her act I aria. As the villainess matchmaker Babarikha, Mariana Radev is much superior to the sour-voiced Evgenia Verbitskaya for Melodiya. There is a difference being using a fine voice to portray an ugly character and simply having an ugly voice; to my ear, Radev exemplifies the first and Verbitskaya the second. In the high tessitura role of the Swan Princess, the sopranos in both sets again excel; I once more slightly prefer the sweeter tone of Maria Glavašević to the more metallic one of Galina Oleinichenko for Melodiya, though a certain harshness in the latter’s recorded sound may also be a factor here. Likewise, the two key male roles in both sets are well cast, and preferences regarding them will be primarily subjective. As Prince Gvidon, Vladimir Ivanovsky for Melodiya is more robust and heroic, in the mold of Georgi Nelepp, whereas Janec Lipusek has a lighter, silver-toned sweetness that recalls Sergei Lemeshev. As Tsar Saltan, Ivan Petrov for Melodiya is more baritonal and gruffer in timbre, whereas Zdravko Kovač has a deep, rich, mellifluous bass that falls far more graciously on my ear. In the supporting male roles, however, there is no contest in my view. The Melodiya singers are markedly inferior to their Philips/Pristine counterparts in every way: The former respectively evince a less refulgent voice (the Old Grandfather), a slightly more nasal timbre (the Jester), and an unsteady vibrato and faulty intonation due to exaggerated interpretive mannerisms (the Messenger), whereas the latter have beautiful voices and faultless singing worthy of casting in far more prominent roles. Likewise, while the three sailors for Melodiya range from acceptable (the first and third) to good (the second), their counterparts for Pristine are all excellent. Most opera companies should be green with envy at comprimario singers of this caliber.

Both choruses and orchestras fulfill their roles well; I agree with Dan on the overall superiority of the Bolshoi Opera chorus and orchestra over the Zagreb forces, though the differences between them are not great. We do again differ in our reactions to the conductors. Vasily Nebolsin is indeed brisker and more pointed in his leadership, but I find Dimitry Zebre not at all sluggish or unimaginative, being instead ingratiatingly lyrical and relaxed in allowing the fairy tale to unfold, and both approaches appeal to me equally. As for the respective sound quality of the two sets, I find my sympathies divided. The Melodiya recording has more punch and presence, whereas the beautifully clean Pristine transfer of the Philips set by comparison preserves the latter’s slightly recessed acoustic; but the Melodiya also has the typical harsh edge and grittiness of Soviet-era recordings, whereas its rival has an attractive roundness and mellowness. The points on where the Melodiya set has decided advantages are in its detailed accompanying booklet (Pristine as usual provides minimal documentation) and far more generous cueing points (54 tracks total, compared to only 17 for Pristine). The Pristine set originally mislabeled some tracks of its second disc on its back tray card; this has now been corrected, and the new version can be downloaded from Pristine’s web site.

Both recordings, then, are quite satisfying, and fans of Rimsky-Korsakov’s operas may well want them both. However, if one prefers to have only a single version, a choice between them comes down to a personal choice of the relative importance one assigns assigned to various factors. My colleague Dan quite reasonably plumps for the Melodiya set; my preference instead is unequivocally for this Pristine version, and I accordingly give it my enthusiastic endorsement.

James A. Altena

This article originally appeared in Issue 39:3 (Jan/Feb 2016) of Fanfare Magazine.