This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

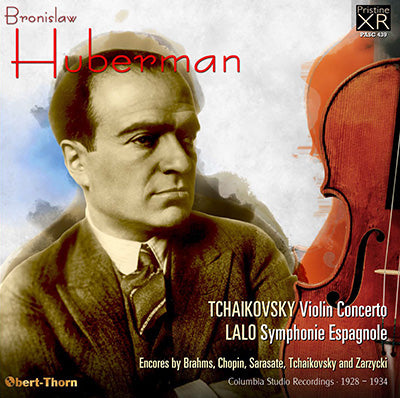

Huberman's magnificent Tchaikovsky and Lalo - and more!

"This is a release of truly historic importance" - Fanfare

"There are no greater violin recordings in existence" - Gramophone

Bronislaw Huberman’s 36-year recording career began with four sides for Berliner in 1899 and continued in a series of piano-accompanied acoustics for American Brunswick (1921 - 1925). But it was not until he started making electrical recordings for Columbia in Europe (1928 – 1935) that he was first heard on disc with orchestra. The Tchaikovsky Concerto presented here comes from his first session for the label; but there would be a hiatus of six years before he would record any more concertos, and the rest were all done in a group of concentrated sessions in a single month.

During a ten-day period from June 13th through the 22nd in 1934,

Huberman recorded the two Bach violin concertos and the Mozart 3rd under

Issay Dobrowen (all on Pristine PASC 397), followed by the Beethoven

(PASC 421) and the present Lalo Symphonie espagnole with George

Szell. The sessions were a logistical nightmare: the hall was often

in use for other functions; the orchestra was playing at a special

festival every night; and Szell had to commute between Vienna and

Prague, where he conducted evening performances after spending the days

recording.

Added to this was Huberman’s own highly-strung temperament. As

Columbia A&R rep Rex Palmer wrote to his London home office at the

time, the violinist “broke down in the middle of a record on innumerable

occasions, and even after obtaining a [completed] master he needed 5 or

10 minutes rest before anything further could be done.” Despite the

various tribulations, Huberman produced classic accounts of all the

works recorded, not the least of which was the Lalo. Through the rather

over-reverberant hall sound and occasional technical imperfections of

the original recording, we hear a performance of great panache and

dazzling, insouciant virtuosity.

The Tchaikovsky Concerto shows another aspect of Huberman’s art. Critic Hans Keller famously called the violinist “part gypsy, part saint”; and while the Bach concertos embody the latter quality, the Tchaikovsky is perhaps the best example of the former. No soloist today would dare to play the work with the kind of rough-hewn individuality and disciplined abandon that Huberman brings to it. When we hear it, we are reminded anew why we listen to historical recordings. Huberman is partnered here with the conductor then known as Hans Wilhelm Steinberg, with whom he would go on to co-found the Palestine Symphony Orchestra (later to become the Israel Philharmonic) some eight years later.

After his recording career reached a premature end, Huberman would continue to play the concerto repertoire in concerts, some of which were broadcast and preserved on disc. A Mozart 4th under Bruno Walter survives (PASC 397), as does the Brahms with Rodzinski (PASC 421), another Beethoven with Leon Barzin and, just a year before his death, another Tchaikovsky with Ormandy. Unlike those performances, fine as they are, the recordings on this collection catch him at the height of his powers, before the 1937 plane crash that injured his hands. They stand as a testament to one of the greatest of all violinists and recreative artists.

Mark Obert-Thorn

HUBERMAN: TCHAIKOVSKY Violin Concerto, LALO Symphonie Espagnole

Encores by Brahms, Chopin, Sarasate, Tchaikovsky and Zarzycki

Columbia Studio Recordings ∙ 1928 – 1934

TCHAIKOVSKY: Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35

1. 1st Mvt.: Allegro moderato – Cadenza (16:04)

2. 2nd Mvt.: Canzonetta: Andante (6:06)

3. 3rd Mvt.: Finale: Allegro vivacissimo (6:00)

Staatskapelle Berlin ∙ William Steinberg

Recorded 28 & 30 December 1928 in the Beethovensaal, Berlin

Matrix nos.: WAX 4509-2, 4510-1, 4511-1, 4512-2, 4513-2, 4514-1 &

4515-2

First issued on Columbia L 2335 through 2338

4. TCHAIKOVSKY: Mélodie, Op. 42, No. 3 (3:29)

Recorded 22 February 1929 in the Columbia Petty France Studio, London

Matrix no.: WAX 4671-1

First issued on Columbia L 2338

5.

CHOPIN (arr. Huberman): Waltz in C-sharp minor, Op 64, No. 2

(3:15)

Recorded 22 February 1929 in the Columbia Petty France Studio, London

Matrix no.: WAX 4672-2

First issued on Columbia LX 137

6. BRAHMS (arr. Joachim): Hungarian Dance No. 1 in G minor (3:01)

Recorded 7 February 1932

Matrix no.: IDWA 9155-5

First issued on Columbia LB 8

7.

SARASATE: Romanza andaluza (No. 1 from Danzas españolas, Op.

22)

(4:39)

Recorded 10 June 1929 in the Columbia Petty France Studio, London

Matrix no.: WAX 5006-1

First issued on Columbia L 2332

8. ZARZYCKI: Mazurka in G major, Op. 26 (4:22)

Recorded 11 June 1929 in the Columbia Petty France Studio, London

Matrix no.: WAX 5011-1

First issued on Columbia L 2332

Siegfried Schultze (piano)

LALO: Symphonie espagnole, Op. 21

9. 1st Mvt.: Allegro non troppo (7:22)

10. 2nd Mvt.: Scherzando: Allego molto (3:49)

11. 4th Mvt.: Andante (6:02)

12. 5th Mvt: Rondo: Allegro (7:54)

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra ∙ George Szell

Recorded 20 & 22 June 1934 in the Mittlerer Konzerthaussaal, Vienna

Matrix nos.: WHAX 39-3, 40-2, 41-2, 42-1, 43-3 & 44-1

First issued on Columbia LX 347 through 349

Bronislaw Huberman (violin)

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

Additional restoration and pitch stabilisation by Andrew Rose

Total Timing: 72:04

Fanfare Review

The performances are unique. There really was no other violinist quite like Huberman

I can join a long line of Fanfare critics (as well as many others) in praising these recordings, which have been classics since they were made (the Tchaikovsky in 1928, the Lalo in 1934, and the miniatures 1929–1932). You can go to the Fanfare Archive and read enthusiastic raves (and excellent descriptions too) by John Bauman in 12:4 and 16:5 (the latter the Lalo only), by David Nelson in 14:4, and Lynn René Bayley in 36:6. Bayley’s review was of a Japanese reissue on the Opus Kura label, and I was able to make a direct A-B comparison between the Opus Kura and the Pristine. More importantly, I was able to compare the Pristine with the excellent Naxos transfer of the Tchaikovsky made by Mark Obert-Thorn (paired with a less successful transfer of the Huberman/Szell Beethoven Concerto) issued in 1999. Whatever comparison you make, this now becomes the preferred version of both of these big works, with the miniatures making a lovely bonus.

The Opus Kura transfer was noisy and a bit harsh. Their engineers obviously took a minimalist approach to removing surface noise from the original 78s, and one admires the purism of that style of transferring. However the result had a distracting amount of noise, and frankly also a hardness of tone to Huberman’s playing and the orchestral strings.

The Naxos transfer from 1999 was the

best to that date of the Tchaikovsky, and it stood the test of time for

well over a decade. The Lalo has never had a truly first-rate transfer.

But Andrew Rose has trumped all of his predecessors. There is less noise

on the Tchaikovsky than is audible on Naxos’s transfer, but Rose has

managed to remove that noise without negatively affecting the sound of

the soloist or orchestra. And his XR stereo approach adds some air and

space to the overall soundstage without detracting from clarity or

presence. It is difficult to imagine that anyone will ever make these

sound better, though I suppose I might have said that after the Naxos

Tchaikovsky release. At any rate, this is the version to have of these two classic performances. [*see note below]

The performances are unique. There really was no other violinist quite like Huberman, and you can get a sense of that from reading the reviews in the Fanfare Archive that I cited above. Huberman could produce a beautiful, rich tone (listen to the Andante of the Lalo or the Canzonetta of the Tchaikovsky), but beautiful tone was not the centerpiece of his art. Huberman was, in my view, about spontaneous flair, spur-of-the-moment drama that nonetheless didn’t pull the piece out of shape.

I think this is the very first recording of the Tchaikovsky Concerto. That it has remained available to the public on various labels on both LP and CD in the 87 years since it was made already makes a statement about its quality. Huberman’s highly individual use of portamento and rubato, his phenomenal ability to employ a spiccato technique with a musicality and accuracy that are uncanny, his feel for the ebb and flow of Tchaikovky’s line, and the feeling he conveys that he is composing the music as he plays it, combine to make this an extremely important and valuable recording of a cornerstone of the repertoire. The Canzonetta is a model of how to use rubato effectively to enhance a melodic line. Other critics have observed that Huberman did not concern himself with “elegance,” with the niceties of avoiding occasional scrapings or edgy sounds. He was, frequently, going for excitement and creating musical fire, and if a bit of beauty were to be sacrificed, all well and good. However much you admire and enjoy Heifetz, Oistrakh, Milstein, Elman, or any other master violinist, it is essential that you know this recording. It is unlike any of the others. William Steinberg’s flexible accompaniment, and orchestral playing with a real sense of occasion about it (after all, making a complete recording of a violin concerto was not an everyday occurrence back in 1928) add to the total.

The Lalo is perhaps not as definitive a recording, if only because it followed the then common practice of omitting the third movement Intermezzo. Still, that same sense of “making it up on the spot,” a kind of excitement of discovery of the music that we rarely get in performances, is present here. And George Szell, by treating the score with the same respect he might give a Mozart or Beethoven concerto, and by getting razor-sharp playing from the Vienna Philharmonic, also makes a major contribution to the whole.

One can feel a smile in the face during the playing of the miniatures. Clearly Huberman is having fun with the Sarasate and Zarzycki pieces (I wish Pristine had included what I consider to be Huberman’s greatest recording—Sarsate’s Carmen Fantasy), and all are transferred with a more natural sound than previous efforts. They make a lovely bonus.

For anyone to whom the violin is an important instrument, and to anyone for whom the Tchaikovsky and/or Lalo works are important pieces in the repertoire, this is a release of truly historic importance. “Historic” can be an overused word, but in this case it applies perfectly.

Henry Fogel

This article originally appeared in Issue 39:1 (Sept/Oct 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.

*NB. This is a mono release prepared for Pristine by Mark Obert-Thorn, not, as the reviewer mistakenly implies, an XR Ambient Stereo release remastered by Andrew Rose