This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Sleevenotes

This release commemorates a brief yet memorable collaboration between a great conductor and orchestra. Dimitri Mitropoulos (1896 – 1960) was born in Athens, mentored in Paris by Saint-Saëns, trained in Berlin under Busoni, and spent his early career in Europe before making a spectacular debut as a guest conductor in Boston in 1937. He was quickly snatched up by the Minneapolis Symphony, which was looking to fill the vacancy left by Eugene Ormandy’s move to Philadelphia. He stayed in Minneapolis until 1949, when he was named co-director of the New York Philharmonic with Stokowski, moving up to sole directorship the following season.

Before that, however, Mitropoulos had a close relationship with the Philadelphia Orchestra. For several seasons during the 1940s, he was the music director of the Robin Hood Dell Orchestra of Philadelphia, an ensemble primarily made up of members of the Philadelphia Orchestra less a handful of their first-desk players. The orchestra performed during the summer at the Robin Hood Dell, an outdoor amphitheater which opened 90 years ago this July, 2020. (The Dell hosted the orchestra from 1930 through 1975 before their move to the Mann Center for the Performing Arts. Until 1970, they performed there under the Robin Hood Dell Orchestra name. The venue itself continues to be used for popular concerts as the Dell Music Center.) At the same time, Mitropoulos appeared as guest conductor with the Philadelphia Orchestra during their regular concert season.

This release combines all of the commercial recordings Mitropoulos made with the Robin Hood Dell Orchestra with the only two broadcasts in which he conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra. While most of the Dell recordings (actually made in the Academy of Music) appeared on a 1998 Lys CD, the Mozart Two-Piano Concerto and the Mascagni Cavalleria Intemezzo have been harder to find. New transfers from the best original commercial releases have been made for the present reissue using state-of-the-art iZotope RX restoration software.

Despite the pre-recorded audience noise at the beginning, the two Philadelphia Orchestra broadcasts for CBS were done as hour-long programs in an empty Academy shortly before the ensemble’s regular Saturday night concerts. Not only have the works from these concerts never before been issued in their entirety, but none of the music was commercially recorded by Mitropoulos, making their release here doubly valuable. The appearance of the Beethoven Fourth is particularly welcome in that no other Mitropoulos version has ever appeared before, and it brings his Beethoven symphony cycle one step closer to completion. (Only a Seventh Symphony still remains to be found.)

Mitropoulos was known for his flexible sense of rhythm, his championing of contemporary music, and his total commitment to his performances. One can hear this throughout the works presented in this set, particularly in the Menotti Sebastian Suite and the Prokofiev Third Piano Concerto, which Mitropoulos directs from the piano (a feat also captured in live performances with the NBC Symphony and the New York Philharmonic). Even Rogal-Levitzky’s over-the-top, kitchen-sink orchestration of Chopin piano works receives Mitropoulos’ all-in enthusiasm. I hope you will enjoy this glimpse into a particularly starry chapter in the histories of this conductor and orchestra.

Mark Obert-Thorn

MITROPOULOS in Philadelphia

CD 1 (68:51)

1. RADIO Introduction (0:37)

2. MOZART: The Magic Flute – Overture (6:40)

From the CBS broadcast of 20 December 1947

BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 4 in B flat, Op. 60

3. 1st mvt. – Adagio – Allegro viviace (11:01)

4. 2nd mvt. – Adagio (10:21)

5. 3rd mvt. – Allegro vivace (6:00)

6. 4rd mvt. – Allegro ma non troppo (5:38)

From the CBS broadcast of 21 December 1946

REGER: Four Tone Poems after Böcklin, Op. 128

7. The Hermit Playing Violin (Alexander Hilsberg, solo violin)

(10:47)

8. In the Play of the Waves (3:49)

9. The Isle of the Dead (9:21)

10. Bacchanal (4:38)

From the CBS broadcast of 20 December 1947

CD 2 (77:53)

IBERT: Escales (Ports of Call)

1. Rome – Palermo (6:34)

2. Tunis – Nefta (2:31)

3. Valencia (6:25)

From the CBS broadcast of 20 December 1947

4. R. STRAUSS: Der Rosenkavalier – Suite (23:24)

From the CBS broadcast of 21 December 1946

Dimitri Mitropoulos ∙ The Philadelphia Orchestra

MOZART: Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra in E flat, K365

5. 1st mvt. – Allegro (9:32)

6. 2nd mvt. – Andante (7:29)

7. 3rd mvt. – Rondo (Allegro) (6:55)

Vitya Vronsky

and Victor Babin, pianists

Recorded 21 September 1945 ∙ Matrices: XCO 35212/4 & 35221/3 ∙ Columbia

12389/91-D in album M-628

8. PUCCINI: Manon Lescaut – Intermezzo (3:47)

Recorded 26 July 1946 ∙ Matrix: XCO 36692 ∙ Columbia 12981-D in album

MX-317

9. MASCAGNI: Cavalleria Rusticana – Intermezzo (3:59)

Recorded 26 July 1946 ∙ Matrix: XCO 36693 ∙ Columbia 12982-D in album

MX-317

WOLF-FERRARI: The Jewels of the Madonna

10. Intermezzo No. 1 (3:50)

11. Intermezzo No. 2 (3:28)

Recorded 26 July 1946 ∙ Matrix: XCO 36694/5 ∙ Columbia 12981/2-D in album

MX-317

CD 3 (65:31)

CHOPIN/ROGAL-LEVITZKY: Chopiniana

1. Etude No. 12 in C minor, Op. 10, No. 12 (“Revolutionary”) (2:41)

2. Nocturne No. 13 in C minor, Op. 48, No. 1 (5:51)

3. Mazurka No. 25 in B minor, Op. 33, No. 4 (5:40)

4. Valse brillante No. 14 in E minor, Op. Posth. (2:58)

5. Polonaise No. 6 in A flat, Op. 53 (“Heroic”) (5:49)

Recorded 21 September 1945∙ Matrices: XCO 35215/20 ∙ Columbia 12263/5-D in

album M-598

MENOTTI: Sebastian – Ballet Suite

6. Introduction (2:02)

7. Barcarolle (3:31)

8. Street Fight (1:18)

9. Cortège (3:55)

10. Sebastian’s Dance (2:06)

11. Pavane (3:53)

Recorded 26 July 1946 ∙ Matrices: XCO 36696/9 ∙ Columbia 12571/2-D in album

X-278

PROKOFIEV: Piano Concerto No. 3 in C, Op. 26

12. Andante – Allegro (8:48)

13. Theme and Variations (8:18)

14. Allegro ma non troppo (8:41)

Dimitri Mitropoulos,

pianist

Recorded 26 July 1946 ∙ Matrices: XCO 36686/91 ∙ Columbia 12509/11-D in

album M-667

Dimitri Mitropoulos ∙ Robin Hood Dell Orchestra of Philadelphia

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

Additional noise reduction for Ibert, additional pitch stabilisation: Andrew Rose

All recordings made in the Academy of Music, Philadelphia

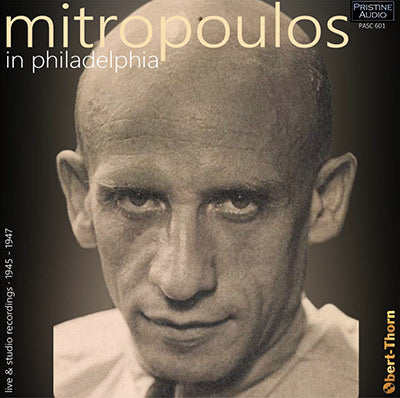

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Dimitri Mitropoulos

Total duration: 3hr 32:16

Dimitri Mitropoulos – A Greek’s Passion

by Gary Lemco

When we consider the artistry and career of Greek conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos (1896-1960), we confront the very tensions that defined his era: art and politics, identity and self-expression, tradition and innovation. In my conversations with Leonard Bernstein and composers David Diamond and Morton Gould on the subject of Mitropoulos, each of them used the word “tragic,” not so much to lament the man’s fate or personality, but to characterize his inward vision, his singularly messianic dedication to his art, even at the cost of social acceptance and success – and more, his palpable sound in the music of such luminaries as Brahms, Scriabin, Mahler, Schoenberg, Vaughan Williams, Krenek, Prokofiev and Shostakovich, that reveals the anguish of their respective worlds.

Born in Athens of a highly religious family, the young Dimitri Mitropoulos might have entered the monastery on Mount Athos and remained there, literally a priest rather than a “priest of art.” But the authorities forbade him even a harmonium in his cell, and he rebelled, entering the Athens Conservatory and mastering the keyboard and musical composition. In 1919, Mitropoulos’ opera Soeur Beatrice (after Maurice Maeterlick) was performed, and on the basis of that success, he sojourned first to Paris for consultation with Camille Saint-Saens, and upon his recommendation on to Berlin (1920) for studies with Ferruccio Busoni and Paul Gilson. The Busoni circle included the gifted pianist Egon Petri (1881-1962) with whom he performed often in Berlin. In 1941 New York City they organized, with Joseph Szigeti, a major tribute to Busoni that included such works as the Violin Concerto and Indian Fantasy. It was a sudden illness that had befallen Petri that required Mitropoulos first to conduct in Berlin the Prokofiev C Major Concerto from the keyboard, a feat he repeated both in later concerts and on record with the Robin Hood Dell Orchestra of Philadelphia.

In Berlin, between 1921 and 1925, Mitropoulos served with the Berlin State Opera, working with Erich Kleiber. After Kleiber left Nazi Germany, Mitropoulos, working with Stokowski at the NBC Symphony Orchestra, influenced authorities that Kleiber should be welcome to lead the NBC in a series of concerts. But it was Boston and Koussevitzky who invited Mitropoulos to debut in the United States. Bernstein, a young, aspiring pianist, composer and conductor, was in attendance. “Mitropoulos led a performance of Ravel’s Rapsodie espagnole that hit me like a revelation. And the sensuality – I tell you, there wasn’t a dry seat in the house!” Mitropoulos, having made an immediate sensation, accepted the duties of leading the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, replacing Eugene Ormandy, who had assumed the post at the Philadelphia Orchestra. C. Ryan Hill, reviewing Mitropoulos in Minneapolis, praised the “French” sound Dimitri elicited from the brass, “gushing” crescendos, the genuineness and compelling quality of the Mitropoulos sonic image, the rapport between conductor and his loyal ensemble. There were, however, those complaints about Mitropoulos’ selected repertory, which would challenge traditionalists with strong doses from the Second Viennese School as well as contemporary American composition, some of which Mitropoulos himself commissioned. “What bothered many about Dimitri in Minneapolis and New York City,” proffered David Diamond in my interview with him at Juilliard, “was his odd juxtaposition of musical styles. He’d schedule quite imposing works – a Prometheus of Scriabin, the Chausson B-flat Symphony, a Mahler Sixth; and then, virtually out of nowhere except his facile imagination, you’d get Three Dances from Falla or Marche Joyeuse!” A case in point is the somewhat jarring presence of the Ibert Escales directly following on the heels of the moody Boecklin Poems by Reger on the 20 December 1947 concert by the Philadelphia Orchestra presented here.

The cry of conservatism found its most rabid spokesperson in Howard Taubman of The New York Times in August 1956, who excoriated Mitropoulos for what Taubman construed as a lack of orchestral discipline and a failure to maintain the prestige of the Philharmonic. Taubman deplored Mitropoulos’ seeming lack of sympathy for the standard Classical repertory and early Romantic music: the “feverish intensity” Mitropoulos brings to “areas of twentieth century music . . . Richard Strauss, Mahler, Schoenberg, or Berg . . . to a Puccini opera . . . become failings, for [Classical] works need proportion and delicacy.” “It is true,” observed Stefan Bauer-Mengelberg (1927-1996), assistant conductor at the Philharmonic, “that Dimitri seemed to court complexity. His eidetic memory would seize the entire score of Wozzeck; and, in the midst of what to others might be cacophony and pure dissonance, he would announce, ‘F-sharp, clarinet, F-sharp,’ and suddenly bring out a Viennese waltz, the ‘human’ element in the most severe aural environment. And when I recall his Mahler Ninth with the Philharmonic, I envision a man’s leading not so much music as an Idea.”

Mitropoulos abdicated his post with the New York Philharmonic, at once mentioning “a stab in the back” and the opportunity to court “that very tempting mistress, the MET.” In 1957, Mitropoulos shared a South American tour with his successor, Leonard Bernstein, and conducted his final New York Philharmonic concerts as music director, subsequently serving at the MET from 1957 onward. Mitropoulos' Philharmonic concerts in January 1960 included a Mahler festival. Mitropoulos remained highly welcome in Europe, having led the Vienna Philharmonic, most notably, the Berlioz Requiem in memory of Wilhelm Furtwaengler. Invitations came not only from Salzburg but from Cologne, Germany; but by 1960 his physical health had been compromised. An avid mountaineer, Mitropoulos no less suffered an addiction to Galoises cigarettes, with frightful damage to his heart. Refusing to cancel his work in Cologne – on the Mahler D Minor Symphony – he sped immediately to Milan to begin rehearsals of that same Mahler Third on November 1. A massive heart attack took him, and he was already dead when he struck the floor.

What is past is prologue. Assessments of Dimitri Mitropoulos maintain his personal lifestyle – as an unapologetic homosexual who eschewed Leonard Bernstein’s option for a “cosmetic marriage” - may have played a role in the decision to remove him from the New York Philharmonic. His personal generosity, however, goes unblemished, from those who consistently mention his donating his own money to purchase musicians’ instruments. Leonard Pennario recalled having suffered a chastisement from Dimitri: “After we performed the Rachmaninoff Second Concerto, Dimitri insisted I take up the G Minor Saint-Saens. My personal ‘snobbery’ at the time balked, and I rather laughed at Dimitri’s suggestion. Well, boy, did he ever lace it into me, reminding me that Saint-Saens had been an early support for his career! I never contradicted him again.” Opera singer Licia Albanese remembered having been nervous about an upcoming opera, not knowing who was to lead the cast and ensemble: “When I saw Mitropoulos stride out from the wings – ‘Maestro Excitement’ we called him – I thought Thank God!”

Of the various performances from Philadelphia presented here, perhaps the most striking and important lies in the live Beethoven Symphony No. 4, especially since his only commercial recording of a Beethoven symphony, the Pastoral from Minneapolis, testifies to Dimitri’s innate ingenuousness in the face of music devoid of crisis. Though Beethoven limits the strongest tension to the opening – thirty- eight harmonically ambiguous measures of jabbing dissonances that might adumbrate some cosmic tragedy – Mitropoulos manages a nervously bizarre atmosphere in B-flat Minor, only alleviated at the repetition of the F chords that signal true jubilation, Allegro vivace.