This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Cast Listing

- Cover Art

- Additional Notes

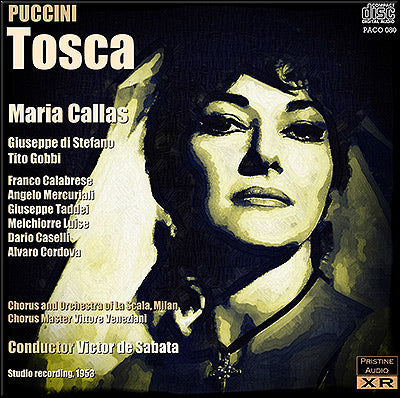

The legendary 1953 Maria Callas recording of Puccini's Tosca

Tremendous improvements in sound quality lift this landmark recording into a new realm

This recording has been issued and reissued so many

times and on so many labels that it seemed futile to begin another

transfer unless something really special and new could be brought to it,

something to distinguish it clearly and dramatically from all that have

gone before. I believe that has been accomplished. Working from mint

French LP pressings, Pristine's 32-bit XR remastering process has lifted

the veil of nearly 60 years to bring a dramatic new life and clarity to

the sound quality familiar to so many for so long.

The result of this process is truly astonishing to hear, and the sound quality revealed is ravishing. In its recommended Ambient Stereo incarnation there's a real sense of space around the performers as well. Finally, analysis of electrical hum buried in the original recording indicates an original performance pitch of A=444.78Hz, which has been preserved for this release.

Andrew Rose

PUCCINI Tosca

Text: Luigi Illica & Guiseppe Giacosa from La Tosca by Victorien Sardou

Producer: Walter Legge

Engineer: Robert Beckett

Recorded 10-21 August, 1953 Teatro alla Scala, Milan

Transfers from EMI box set 2 C 163-000410/1

THE CAST

Maria Callas - Tosca

Giuseppe di Stefano - Cavaradossi

Tito Gobbi - Scarpia

Franco Calabrese - Angelotti

Angelo Mercuriali - Spoletta

Melchiorre Luise - Sacrestan

Dario Caselli - Sciarrone/Gaoler

Alvaro Cordova - Shepherd

Chorus and Orchestra of La Scala, Milan

Chorus Master Vittore Veneziani

Conductor Victor de Sabata

ARTICLE - Callas - The Tosca Sessions (excerpt)

This Tosca was always different; headstrong and full-blooded both when the red recording light was on and when it was off. Truly dramma per musica. Her co-star, the great baritone Tito Gobbi, called it "one of the finest recordings [I] had participated in and one of [my] best experiences of this kind". Sixteen years after the sessions in August 1953, the Svengali-like Walter Legge listened again to the Tosca he had produced for EMI. They had "made immortal contributions through records to the artistic history of our time," he wrote to his heroine, Callas, who was by now living in semi-retirement in Paris. The two had become estranged, and it was, wrote Legge, when he relistened to their Tosca that he realised how trivial their disagreements were in the face of what they had together achieved (the letter worked: the producer and his Tosca were reconciled).

Art had begun as commerce, as is usual with the record business. In the early 1950s, Legge and EMI faced a problem. They were about to launch their own label in the United States, HMV Angel, rather than rely on American companies such as CBS for distribution. To run the new operation they had cunningly poached the formidable husband-and-wife team of Dario and Dorle Soria from Cetra records. EMI knew that Italian opera was a big seller across the Atlantic and the Sorias, according to EMI music consultant Tony Locantro, "were skilled at marketing and promotion and knew the American market very well. Certainly Callas to them looked like an extremely promising and exciting artist who would add lustre to the new Angel catalogue".

As Legge wrote later: "I was rather late on the Callas bus. Italy was not officially my territory." He felt more at home north of the Alps, with Mozart and Herbert von Karajan in particular, but business was business and was, as ever, driven by talent — and the talent who had everyone talking was Callas. "At long last, a really exciting Italian soprano!" wrote Legge. "My appetite was further whetted when one of her famous male colleagues described her as 'not your type of singer'."

A performance of Norma in Rome in 1951 convinced the deeply competitive Legge that he had to have her for EMI, though it would be a year and many meetings before he got her signature on a contract. It hadn't been easy, he recalled. "She expected tribute at every meeting, and my arms still ache at the recollection of the pots of flowering shrubs and trees that Dario [Soria] lugged to the Verona apartment."...

...The last session at La Scala was on August 21. They had been recording with just two free days since the 10th. All were utterly exhausted. Costs, as Walter Legge later grumbled to Lord Harewood, had spiralled as - thanks to the relentless perfectionism - the number of sessions needed had doubled. Wearily, Legge looked at the reels and reels of tape that he and his team would turn into the final product and invited de Sabata to help them select the best takes. "My work is finished", said the maestro. "We are both artists. I give you this casket of uncut jewels and leave it entirely to you to make a crown worthy of Puccini and my work."

For Callas, for Gobbi, for de Sabata himself, this Tosca had been perhaps the most intensive recording project they would ever undertake. And yet, despite the heat, despite the extended recording schedule and the temperament, for once everything locked into place. Callas and her co-stars had set new performance standards for Puccini's opera, which many feel have yet to be surpassed on record. And for the soprano's many fans, just about everything you need to know about her talent, her unique dramatic gifts and the interpretative power of a truly magnificent singing actress is here on this recording.

Christopher Cook, Gramophone June 2007

Fanfare Review

She really was the greatest singing actress of her time

Puccini’s Tosca has been described as a “shabby, little shocker” but the public and performers have made it one of opera’s biggest hits and the recordings keep coming out. Tosca isn’t Salome but I can imagine that the audiences of a century or so ago might have been a little uncomfortable with Sardou’s play, La Tosca, and the opera Puccini and his librettists fashioned from it. After all, after exulting about the joys of taking women by force, the principal villain attempts to rape the star soprano right up there on stage. There are many who consider this particular performance to be the greatest opera recording ever made. I might not go that far but I do believe it’s the greatest recording of Tosca and has remained so for more than 50 years despite some impressive challenges, the most formidable of which comes from a Decca recording that was originally issued here on LP by RCA Victor. Imaginatively produced (John Culshaw), beautifully played (the Vienna Philharmonic), dramatically conducted (Herbert Von Karajan), and splendidly sung (Leontyne Price, Giuseppe di Stefano, Giuseppe Taddei), it compensates in dramatic power for what it lacks in white heat. If it falls just short of this classic EMI recording, it’s because of Maria Callas. First of all, I don’t see how Andrew Rose has managed, without access to EMI’s master tape, to give the original a slightly fuller sound and seemingly pull the voices just a bit closer than they were on my EMI CDs. If it should turn up in a used CD bin, avoid the EMI set with the close-up of Callas’s face on the cover, which lacked interior cueing! The later issues almost certainly do have it but, given this excellent Pristine release, maybe the point is moot. My Pristine CDs came in a narrow double jewel box that has no accompanying libretto but I imagine most likely purchasers won’t need one.

I have, at times, suggested that, if a soprano can convey three emotions: “I am happy” (without laughing), “I am sad” (without sobbing), and “I am angry” (without shouting), she will be accounted a great singing actress. Price, with her beautiful voice (Karajan once said it gave him goose pimples!) could convey these emotions. Callas, with her flawed but flexible voice, could convey nuances like “I am suspicious,” “I am indifferent,” “I am nervous,” and so on. Looking at my score of Tosca, just in act II, I see directions like “pretending calm,” “with simulated indifference,” “with conviction,” “desperately,” “warmly,” “full of hatred and contempt,” “in despair,” and “humbly.” Granted, these directions may come from an editor, rather than Puccini, but they are appropriate and she pretty much nails them. She really was the greatest singing actress of her time. Since I’m in act II, I might as well mention that de Sabata, like most of his colleagues, cuts the three bars that immediately follow “Vissi d’arte” (Scarpia says “Your answer?” She replies “On my knees I beg for mercy.” I have no idea why it gets cut). Di Stefano, as one might expect, is a spirited, impassioned Cavaradossi—there were signs that vocal problems were brewing but, at this stage, they hardly detract from his performance. On the later Karajan recording, his top notes have hardened and have little ring to them but he has the role down pat and most of the di Stefano charm still comes through. De Sabata’s Scarpia, Tito Gobbi was, by acclamation, the world’s champion Scarpia for most of his career. In addition to his intelligence, his lack of a conventionally beautiful sound was probably a contributing factor; the voice was sizeable and dark, with a rough edge to it but he could, when necessary, modulate it and sound ingratiating. At last I get a chance to write something other than conventional wisdom: I think Karajan’s Giuseppe Taddei matches him—he’s just as slimy and menacing but is capable of more smoothness and has adequate power when he needs it and was, himself, an imaginative, versatile performer. Karajan paces the music more slowly than the more volatile de Sabata but punctuates—it’s not a mere reading, and the production, with the usual Culshaw bells and whistles, really does enhance the performance. It’s “staged,” almost as if it’s taking place right before your eyes. You really couldn’t go wrong with either recording or with both of them, for that matter.

There are other worthy recordings too, including an inevitable stereo remake by Callas and Gobbi, with Carlo Bergonzi and Georges Prêtre replacing di Stefano and de Sabata. Their renditions have coarsened a bit, probably due to some vocal wear-and-tear but Callas and Gobbi operating at 90 percent are nothing to sneeze at and Bergonzi, if he lacks Di Stefano’s charisma, nevertheless sings quite beautifully and Prêtre, if he’s no de Sabata, has the measure of the score.

Francesco Molinari-Pradelli leads the almost inevitable Renata Tebaldi/Mario del Monaco recording. It’s well recorded if not as imaginatively as the Culshaw production. Tebaldi is not a strong Tosca (more of a vulnerable one) but her singing was more about making beautiful sounds than projecting character and at that stage of her career, she could still do it—it’s a gorgeous piece of singing, per se. The producer seems to have kept Del Monaco a bit of a distance from the microphones much of the time—a good decision since, up close, his singing could take on a hectoring quality. He sounds more like a warrior than a painter since, when in doubt, he simply turns up the volume as few contemporaries could. With his ringing trumpet of a voice, he was more effective in person but he certainly has his good moments here. Unfortunately, with his imposing stage presence, George London was a singer who had to be seen as well as heard, as Scarpia or just about anything else this versatile bass/baritone performed. The possessor of a big, dark, somewhat unwieldy voice, he’s terrific when Scarpia is at his most menacing, which, granted, is a good bit of the time, but he’s less successful at turning on the charm—we hear the wolf but can’t see the sheep’s clothing. I also have some affection for the 1938 Rome Tosca of Maria Caniglia, Beniamino Gigli, and Armando Borgioli, led with authority by Oliviero de Fabritiis. It gives “routine” a good name. These people know what they’re doing and, basically, deliver the goods. If the result isn’t especially notable for imaginative singing, it’s still a satisfying piece of pour-it-on verismo and Gigli can still utter some ravishing sounds.

James Miller

This article originally appeared in Issue 36:3 (Jan/Feb 2013) of Fanfare Magazine.