This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Coolidge's Address

A century ago, the adoption of electrical recording by major labels on both sides of the Atlantic revolutionized the industry. The old method of recording acoustically through a horn-like apparatus had remained fundamentally unchanged since Edison’s invention of 1877, nearly 50 years earlier. With electrical recording, the frequency range captured on disc was greatly expanded. Instrumentalists and singers now sounded more realistic, and there was no longer a need to rescore orchestral music in order to reinforce the bass using tubas (although at first this continued to be done to accommodate acoustic reproducers). Full symphony orchestras and choruses of hundreds of singers could now be recorded. Moreover, recordings could now be taken outside small studios and into large concert halls, even into the open air.

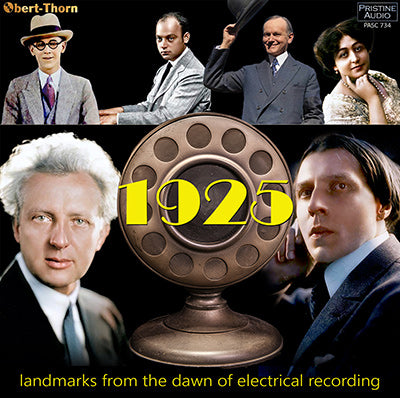

To celebrate this sea change in recording history, Pristine presents in this release the landmark discs from 1925 that forever altered the way people listened to records. All of the major discs that appeared during that year and have long been mentioned in books like Roland Gelatt’s The Fabulous Phonograph (1954; rev. 1977) are here. This development, however, did not come out of nowhere; and our release also features some of the steps that led up to the “electric year”. Also included is the first complete release of all that was recorded of Calvin Coolidge’s Presidential Inauguration ceremony, transferred from rare test pressings.

While claims regarding the “earliest recorded electrical” this or “first issued electrical” that continue to be disputed, one fact that historians have agreed upon is that the first issued electrical recording was made on Armistice Day, 1920, at Westminster Abbey during the ceremony for the interment of the Unknown Warrior of World War I. British engineers Lionel Guest and H. O. Merriman had developed a system utilizing something similar to the speaking end of a telephone as a microphone, transmitting the signal via phone lines to an offsite cutting turntable.

The resultant signal was dim, nearly overwhelmed by the surface noise of the record, and muddied by the vast reverberant space of the church in which it was recorded. (The cutting turntable had not yet come up to speed when "Abide with me" began to be recorded, resulting in the fall in pitch heard as the record begins.) Still, the melodies of the hymns can be clearly discerned, as well as the fact that people are singing (although the text cannot be made out) and that instruments were playing. The record was issued by English Columbia, and sold locally as a fundraiser for the church; but the experiment proved to be a dead end for this system, although it did spur English Columbia to further experimentation in electrical recording over the next few years.

(A note about the pitching of these tracks is in order. At this time, Royal bands still tuned to the Victorian-era “high pitch” of A4=452 Hz. Since the Grenadier Guards would not retire their older instruments until 440 Hz was standardized for Royal bands in 1927, these two tracks have been pitched higher than the others in this release.)

The next two tracks shed light on a pioneer of electrical recording whose work had been largely ignored by (or perhaps unknown to) audio historians until recent years. Orlando R. Marsh was a Chicago-based engineer who developed an electrical system and began issuing recordings using it on his own Autograph label as early as 1922. One of the first performers to gain fame from this source was silent movie house organist Jesse Crawford, who began a forty-year recording career with these discs. Using the old acoustic system with its limited frequency range, it was thought to be impossible to capture the sound of an organ. Marsh was able to accomplish this with his system, even recording Crawford on-site in the large cinema in which he regularly played. Marsh’s system, however, had variable results. The following track, featuring Dell Lampe’s Orchestra (at the time, Chicago’s highest-paid and most popular local dance band) is not quite as successful, exhibiting a more restricted frequency range commonly associated with acoustic recordings.

Since 1919, Western Electric, the commercial research and development arm of Bell Laboratories, had been attempting to develop electrical recording under the direction of Joseph P. Maxfield and Henry C. Harrison. Part of their experiments involved recording broadcast concerts of the New York Philharmonic via direct radio lines. (Pristine has already released several sides recorded in that manner from an April, 1924 concert conducted by Willem Mengelberg on PASC 184.) By late 1924, they had made sufficient progress to offer their system to the two major labels in America, Victor and Columbia. In the same month that Marsh’s Dell Lampe recording was made, Columbia had one of their featured pianists, Mischa Levitzki, make the test recording of Chopin presented here. Even through the surface noise of this unique test pressing, the gain in frequency range and presence is audible.

Surprisingly, Western Electric’s offer at first did not attract any takers. American Columbia was nearly broke and couldn’t afford the licensing fee and royalties being demanded, while Victor’s management had an almost pathological aversion to anything related to its growing competitor, radio, including the use of microphones. It was only after a disastrous Christmas sales season at the end of 1924 that Victor bit the bullet and became open to the offer.

In the meantime, the manager of the New York plant where Western Electric was having its test records pressed surreptitiously sent copies of some of the discs to an old friend in England – Louis Sterling, the head of English Columbia. The package arrived on Christmas Eve, 1924, and Sterling auditioned the discs on Christmas day. The following day, he was aboard the first ship he could book to New York, eager to cut a deal with WE. For their part, WE insisted that the rights could only be granted to an American company; so Sterling swiftly obtained a loan to buy a controlling interest in American Columbia. Shortly afterward, Victor signed up, as well.

By early February, 1925, Victor had set up a special studio in Camden to work exclusively on test recordings using the new system. The Giuseppe De Luca recording included here, from a test pressing unpublished on 78 rpm, was made during this interim period. (British record collector and researcher Jolyon Hudson has identified several sides believed to stem from these trials that were sent over to HMV after March, 1925 and issued in England. However, because Victor did not include recording matrix or date data for these electric tests in its surviving logs, it is impossible to know with certainty whether these sides predate the label’s first electrical releases.)

By the end of February, Victor was ready to proceed with recording electrically with a view to publish. However, they were pipped to the post by rival Columbia, who made two sides which, coupled on a single disc, became the earliest Western Electric process electrical recordings to be issued. Art Gillham, who was billed as “The Whispering Pianist”, had made a successful career on the radio with his intimate, confessional singing, presaging the kind of “crooning” that electrical recording would make possible and which would change the direction of popular singing. Sibiliants that could never be recorded acoustically could finally be heard. Gillham (who was neither fat nor bald, as he described himself in “I had someone else”, but rather resembled silent film comedian Harold Lloyd, even down to his trademark glasses) was surprised when Columbia granted him a bonus of one thousand dollars – then a princely sum – to have been their electrical guinea pig.

The very next day, Victor recorded its own earliest electrical disc to be issued, featuring several of its best-selling popular acts on what amounts to an elaborate demo record. Acts which had been recording for over a decade, like Billy Murray, the Peerless Quartet and the Sterling Trio, were placed side-by-side with jazz instrumentalists and a dialect comedian, performing operetta arias, Victorian-era ballads and plantation songs – a true snapshot of mainstream American popular culture of the time. (The reference to Henry Ford here was not due to his musical accomplishments – although he was an avid fan of country fiddling who owned an array of rare violins, including Stradivari – but to the nickname of his famed Model T, the “Tin Lizzie”.)

But “earliest recorded” is not always “first issued”; and the prize for that goes to the two tracks that follow. Someone at the University of Pennsylvania’s theatrical Mask and Wig Club must have known someone at Victor; for how else could they have gotten a recording made of highlights from their latest annual musical, Joan of Arkansas, with members of their all-male glee club backed by Nat Shilkret and Victor’s crack band? Suffice it to say that the mid-March recording made it to local Philadelphia stores by April, and the rest is history.

Victor and Columbia had agreed that no mention would be made of the new electrical process prior to November. Both companies had sizeable stocks of existing acoustic recordings in the catalog and new ones waiting to be released, most of which would be considered obsolete once the new technology was identified. (English Columbia had been in the midst of a major program of recording complete Classical works – symphonies and chamber music – acoustically, and would be the most harmed by the changeover.) Nonetheless, reviewers who knew what was up found ways to indicate that these records had a startlingly new presence without violating the ban.

The next six tracks document “firsts” of different varieties. Contralto Margarete Matzenauer set down two sides on March 18th which became the earliest-recorded issued vocal sides made by a Classical artist using the Western Electric process. They were coupled with sides recorded the following day and issued on separate discs (one ten-inch, the other twelve). Although her vibrato was a bit wide by this point in her career, the power behind her high notes is certainly made clear by the new technology.

The following tracks by pianist Alfred Cortot were coupled on the Victor’s first electrical Red Seal release (6502). Oddly, the HMV issue of the Chopin Impromptu coupled it with the second half only of Chopin’s G-minor Ballade, and this version of Cortot’s Schubert song transcription was not released in Europe at all. (Neither was the “Ballade Fragment”, as it was billed, released in the U.S.)

The next two tracks come from a ten-inch side which was part of a set of two discs (the other twelve-inch) containing Bizet’s complete Petite Suite, his orchestrated version of several numbers drawn from his piano collection, Jeux d’enfants. It demonstrates that Victor had already recorded a Classical orchestral work over a month before Stokowski would conduct his own first Victor electric, Danse Macabre. Surprisingly, both discs of the Bizet, the uncredited work of Victor house conductor Josef Pasternack, would remain in the catalog until the end of the 78 rpm era.Perhaps no other single disc helped to sell the public on the new process more than Columbia’s Associated Glee Clubs of America coupling of “John Peel” and “Adeste Fidelis”. During the acoustic era, one was likely to encounter on disc a chorus of eight voices (the number used in Albert Coates’ 1923 recording of the Beethoven Ninth), about as many as could fit in a small recording studio alongside a reduced orchestra. But the Columbia release, recorded during a live performance at the old Metropolitan Opera House in New York, boasted 850 voices for “John Peel” and a whopping additional 4,000 voices for “Adeste”, counting the total number of the audience that was invited to join in for the final verse. (Truth be told, no more voices can be discerned on this track than on the other, possibly because the rather directional microphone used was focused on what was happening onstage, not in the audience.) As Roland Gelatt wrote in The Fabulous Phonograph,

It was staggeringly loud and brilliant (as compared to anything made by the old method), it embodied a resonance and sense of “atmosphere” never before heard on a phonograph record, and it sold in the thousands. Although [it] was not the very first electrical recording to reach the public, it was the first one to dramatize the revolution in recording and the first to make a sharp impression on the average record buyer.

The focus on the Western Electric system has all but obscured the short-lived rival process developed by General Electric, the so-called “Light-Ray” system, used by its licensees Brunswick and Grammophon/Polydor until 1927. This employed a beam of light to convey electrical impulses to the disc cutting head. The Prelude from Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana included here was the earliest issued Brunswick electrical recording (noted by the “E” in the “XE” matrix prefix). The general drawback of this system was that it tended to distort at higher volume levels, although it works well in this mostly quiet music.

Following this track is what history books have generally cited as the earliest electrical recording of a symphony orchestra (although, as we’ve seen, it was predated by both Brunswick and Victor itself). Leopold Stokowski’s disc of Saint-Saëns’ Danse Macabre utilized the same kind of rescoring that was done for acoustic sessions in order to bolster bass frequencies for acoustic horn reproducers. Here, string basses were replaced by a tuba, and a contrabassoon substituted for the tympani, giving the resulting performance a weirder, even more disconcerting sound than the composer originally intended.

On May 15th, Stokowski began recording Dvořák’s New World Symphony. Had he finished it around that time, it would have been the first electrical recording of a symphony. As it was, however, the sessions continued through December; and by then, Sir Landon Ronald’s electrical set of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony had been released in the UK. Ronald conducted the Royal Albert Hall Orchestra from its start (as the New Symphony Orchestra) in 1908 until its dissolution in 1928. He recorded extensively for HMV throughout his career, both as conductor and piano accompanist.

His Tchaikovsky Fourth, recorded at HMV’s Hayes studios in July of 1925, uses tuba reinforcement for the string basses (as HMV would continue to do through at least early 1927), although we are spared Stokowski’s contrabassoon in lieu of the tympani, a decided advantage at the ends of the outlying movements. Ronald could be a variable interpreter, but here he turns in an exciting and highly satisfying performance which checks all the right boxes. Gramophone’s editor Compton Mackenzie was not pleased, however, writing that there seemed to be “something almost deliberately defiant in choosing this particular work for a symphonic debut in the latest methods of recording,” citing the music itself being “a jangle of shattered nerves” which was only magnified by the harshness of the new process. It would take the changeover to electrical reproducers to enable listeners to fully appreciate what the new records could convey.

Placed at the end of our survey for programming purposes is another example of what the electrical process could now capture. When the previous U.S. presidential election had taken place in 1920, radio was in its infancy, and only the results of the polls were broadcast as they came in. By March, 1925, a presidential inauguration could not only be sent out as it happened on the radio, but also simultaneously preserved for posterity on an electrical recording.

Bell Laboratories spared no expense for this technological demonstration. Loudspeakers were installed at school auditoriums throughout the country for students to hear the broadcast live, and seven sides were recorded from the direct line. No attempt was made to record the complete speech, which was twice as long as the extant excerpts. Comparing the records to the complete text of Coolidge’s speech (reproduced on the webpage for this release) shows how much was left out. The transfer here from unpublished test pressings is complete as recorded, with only some lengthy spots of “dead air” edited out. Portions have previously appeared online, but this is the first publication of the entire recording, including the oath of office given by Supreme Court Chief Justice (and former President) William Howard Taft in his only electrical recording, and the U.S. Marine Band playing “Hail to the Chief” at the end.

Mark Obert-Thorn, January, 2025

1925: Landmarks from the Dawn of Electrical Recording

Disc 1 (66:09)

1. MONK Abide with me (2:50)

2. DYKES Recessional (3:34)

Choir, Congregation and Band of H. M. Grenadier Guards

Recorded 11 November 1920 in Westminster Abbey, London ∙ Matrices: unknown ∙

First issued on unnumbered Columbia “Memorial Record”

3. JONES & KAHN The one I love belongs to somebody else (3:17)

Jesse Crawford, organ

Recorded c. December, 1923 in the Chicago Theater, Chicago ∙ Matrix: 447 ∙

First issued on Autograph (no catalog number)

Dell Lampe Orchestra from the Trianon Ballroom/Al Dodson, vocal chorus

Recorded c. November, 1924, Chicago ∙ Matrix: 658 ∙ First issued on

Autograph 604

Mischa Levitzki, piano

Recorded 19 November 1924, New York ∙ Matrix: 6466-1 ∙ Columbia (unpublished

on 78 rpm)

6. CIMARA Stornello (Son come i chicchi) (3:03)

Giuseppe De Luca, baritone/Orchestra conducted by Rosario Bourdon

Recorded 17 February 1925, Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrix: WER-3719 ∙ Victor

(unpublished on 78 rpm)

8. STANLEY, HARRIS & DARCEY I had someone else before I had you*

(3:17)

Art Gillham, piano and vocal

Recorded 25 February 1925 in New York ∙ Matrices: 140125-7 & *140394-2

∙ First issued on Columbia 328-D

9. THE EIGHT POPULAR VICTOR ARTISTS A miniature concert (9:29)

Opening Chorus; “Strut Miss Lizzie” – Frank Banta, piano; “Love’s old sweet

song” – Sterling Trio; “Friend Cohen” – Monroe Silver, speaker; “When you

and I were young, Maggie” – Henry Burr, tenor; “Casey Jones” – Billy Murray,

tenor and Chorus; “Sweet Genevieve” – Albert Campbell, tenor and Henry Burr,

tenor; “Saxophobia” – Rudy Wiedoeft, saxophone; “Gypsy Love Song” – Frank

Croxton, bass; “Carry me back to old Virginny” – Peerless Quartet; “Massa’s

in de cold, cold ground” – Chorus

Recorded 26 February 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrices: CVE 31874-3 and

31875-4 ∙ First issued on Victor 35753

10. GILPIN Joan of Arkansas – Medley (3:15)

Mask and Wig Glee Chorus; Orchestra conducted by Nathaniel Shilkret

Recorded 16 March 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrix: BVE 32160-2 ∙ First

issued on Victor 19626

11. GILPIN Joan of Arkansas – Buenos Aires (3:37)

Arthur Hall, tenor; Bernard Baker, cornet solo; International Novelty

Orchestra conducted by Nathaniel Shilkret

Recorded 20 March 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrix: BVE 32170-2 ∙ First

issued on Victor 19626

12. MEYERBEER Le prophète – Ah, mon fils! (4:36)

13. MEXICAN FOLK SONG Pregúntales á las estrellas* (3:23)

Margarete Matzenauer, contralto; Orchestra conducted by Rosario Bourdon

Recorded 18 March 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrices: CVE 31632-3 and

*BVE 31629-4 ∙ First issued on Victor 6531 and *1080

15. CHOPIN Impromptu No. 2 in F sharp major, Op. 36* (4:41)

Alfred Cortot, piano

Recorded 21 March 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrices: CE 22512-11 and

*31689-5 ∙ First issued on Victor 6502

BIZET Petite suite (from Jeux d’enfants)

16. 1st Mvt.: Marche (2:09)

17. 3rd Mvt.: Impromptu (1:03)

Victor Concert Orchestra conducted by Josef Pasternack

Recorded 23 March 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrix: BE 32179-3 ∙ First

issued on Victor 19730

19. WADE Adeste fideles* (2:43)

Associated Glee Clubs of America

Recorded 31 March 1925 in the Metropolitan Opera House, New York ∙ Matrices:

W98163-1 and *W98166-1 ∙ First issued on Columbia 50013-D

Disc 2 (74:13)

1. MASCAGNI Cavalleria rusticana - Prelude (4:45)

Metropolitan Opera Orchestra conducted by Gennaro Papi

Recorded 8 April 1925 in Room No. 3, 799 Seventh Avenue, New York ∙ Matrix:

XE 15472 or 15473 ∙ First issued on Brunswick 50067

Thaddeus Rich, solo violin

The Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Leopold Stokowski

Recorded 29 April 1925 in Camden, New Jersey ∙ Matrices: CVE 27929-2 &

27930-2 ∙ First issued on Victor 6505

TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Op. 36

3. 1st Mvt.: Andante sostenuto (17:38)

4. 2nd Mvt.: Andantino in modo di canzona (7:51)

5. 3rd Mvt.: Scherzo: Pizzicato ostinato (5:22)

6. 4th Mvt.: Allegro con fuoco (8:45)

Royal Albert Hall Orchestra conducted by Sir Landon Ronald

Recorded 20, 21 & 27 July 1925 in Hayes, Middlesex ∙ Matrices: Cc

6374-2, 6375-3, 6376-3, 6377-2, 6378-2, 6379-2, 6381-1, 6410-1, 6380-5 &

6382-2 ∙ First issued on HMV 1037/41

Inauguration of Calvin Coolidge as President of the United States

7. Oath of Office (given by Chief Justice William Howard Taft) (0:57)

8. “My Countrymen . . .” (2:04)

9. “It will be well not to be too much disturbed . . .” (3:28)

10. “Our private citizens have advanced large sums of money . . .” (3:33)

11. “There is no salvation in a narrow and bigoted partisanship” (3:25)

12. “. . . they ought not to be burdened . . .” (3:34)

13. “Under a despotism the law may be imposed . . .” (3:24)

14. “. . . built on blood and force” (0:51)

15. Ruffles and Flourishes/Hail to the Chief (U.S. Marine Band) (1:11)

Calvin Coolidge, speaker

Recorded 4 March 1925 in Washington, D.C. ∙ Matrices: 51175/81 ∙ Columbia

(unpublished on 78 rpm)

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

Special thanks to Gregor Benko, Jim Cartwright’s Immortal Performances, Inc., Cate Gasco, Colin Hancock, Ward Marston, David Mason, Dave Schmutz, the collection of the late Don Tait and Lew Williams for providing source material and/or valuable guidance for this project

Total timing: 2hr 20:22

Complete text of Calvin Coolidge’s Inaugural Address, March 4, 1925

(Recorded portions shown in boldface, and side track beginnings and endings

indicated in italics within paretheses)

(Track 8 start)

MY COUNTRYMEN:

No one can contemplate current conditions without finding much that is satisfying and still more that is encouraging. Our own country is leading the world in the general readjustment to the results of the great conflict. Many of its burdens will bear heavily upon us for years, and the secondary and indirect effects we must expect to experience for some time. But we are beginning to comprehend more definitely what course should be pursued, what remedies ought to be applied, what actions should be taken for our deliverance, and are clearly manifesting a determined will faithfully and conscientiously to adopt these methods of relief. Already we have sufficiently rearranged our domestic affairs so that confidence has returned, business has revived, and we appear to be entering an era of prosperity which is gradually reaching into every part of the nation. Realizing that we can not live unto ourselves alone, we have contributed of our resources and our counsel to the relief of the suffering and the settlement of the disputes among the European nations. Because of what America is and what America has done, a firmer courage, a higher hope, inspires the heart of all humanity. (Track 8 end)

These results have not occurred by mere chance. They have been secured by a constant and enlightened effort marked by many sacrifices and extending over many generations. We can not continue these brilliant successes in the future, unless we continue to learn from the past. It is necessary to keep the former experiences of our country both at home and abroad continually before us, if we are to have any science of government. If we wish to erect new structures, we must have a definite knowledge of the old foundations. We must realize that human nature is about the most constant thing in the universe and that the essentials of human relationshi