This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Reviews

Solomon and the Philharmonia "are at one" in Beethoven's Emperor Concerto

Plus "Solomon's magnificent Waldstein — truly one of the great recordings of the century" - The Gramophone, 1967

Solomon was without doubt one of the foremost Beethoven specialists of his era, as this superb performance of the Emperor amply demonstrates - it was a request for this particular recording which prompted this short series of releases. Alas at this time EMI's adoption of stereo was somewhat patchy - a year later Solomon was still making some of his final sonata recordings in mono. I have chosen two of his 1952 sonata recordings from a similar period in Beethoven's output to join the Emperor here - both again brilliant played and recorded, and all three sounding simply wonderful in these new transfers after 32-bit XR processing. In the case of both sonatas and concerto I was also able to eliminate a hint of wow and flutter present in the originals, firming up the piano tone considerably as well as correcting very slightly wayward pitches (both up and down) to concert standard A=440Hz.

Andrew Rose

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Concerto No. 5, "Emperor", in E flat major, Op. 73

Transfer from EMI HLS 7070

Recorded 13 April 1955 at Abbey Road Studio 1, London

First issued as HMV ALP.1300

The Philharmonia Orchestra

Herbert Menges conductor

-

BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 21, "Waldstein", in C major, Op. 53

Transfer from EMI HLM 7099

Recorded 15 June 1952 at Abbey Road Studio 3, London

First issued as HMV ALP.1160

- BEETHOVEN Piano Sonata No. 26, "Les Adieux", in E flat major, Op. 81a

Transfer from EMI HLM 7101

Recorded 20 November 1952 at Abbey Road Studio 3, London

First issued as HMV BLP.1051

Solomon, piano

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, August 2012

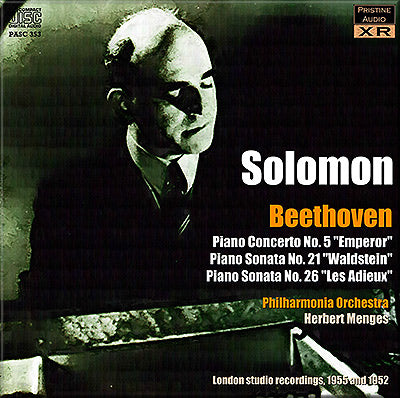

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Solomon

Total duration: 77:11

Review (Piano Concerto No. 5)

The

Emperor is indeed fortunate among concertos, for each new version seems

to manage to improve fairly consistently on the last. The latest is no

exception: on general grounds I would place this new H.M.V. with Solomon

at the top of the list, where previously I had preferred the D.G.G.

with Kempff.

Not altogether expectedly, the new performance seems to concentrate on brilliance. To some small extent an occasional breadth of phrase or an occasional relaxation of tension are sacrificed to the primary end but it cannot be said that the result is not arguably suitable to the nature of the concerto. The Philharmonia, under Menges, and Solomon are at one in this: the orchestra lacks nothing whatever in brilliance, but its wind soloists do not always sound to be fully at their ease. That is not to say that anywhere there is a bar of wind-playing that would not pass muster in any orchestra in the world; but it is to say that occasionally the Philharmonia do sound less distinctive than usual.

The concerted brilliance is naturally in principal evidence in the outer movements; and it combines with a very sure rhythmic grip on Solomon's part to present the finale in a most effective light. The coda is particularly striking; Solomon delays beginning his ritardando to something like the point at which Beethoven marked it, and the notes of the timpani part are clearly audible as such. The result is a highly successful negotiation of one of the traditional danger spots.

The clear timpani at this point are symptomatic of the first-class recording. It is exceptionally clean, and brilliant to a degree matching that of the performance; and this without any suspicion of shallowness in the piano tone, which is full and rounded. The balance between piano and orchestra is nearly everywhere ideal, as is the internal balance of the orchestra. The sense of one passage in the slow movement would be clarified if the flute were slightly more prominent; but happy the recording in which such a comment is worth making!

Happy this recording in any case; and I have no hesitation in strongly recommending it.

M.M., The Gramophone, January 1956

Review (Sonata No. 21)

I

am delighted to see reissued at this bargain price Solomon's

magnificent recording of the Beethoven Waldstein Sonata— truly one of

the great recordings of the century. It was made in 1952 when he was at

the height of his powers, and the Carnaval recording, which has not been

issued before, dates from the same year. With Solomon one always took a

Virtuoso technique for granted. It comes as a surprise even so to be

reminded in a brilliant piece like Carnaval, and also in one of

Beethoven's most brilliant 'concert' sonatas, just how brilliantly he

could play. The Carnoval performance is astonishing: a riot of extrovert

gaiety, colourful to the point of garishness, at times hectic to the

point of sweeping the carnival guests off their feet. Speaking from

memory I would say that of all the other recordings of the work I've

heard Solomon's comes closest to Rachmaninov's in terms of physical

excitement. A commanding interpretation, if not perhaps one which does

full justice to the 'light fantastic' and inward qualities of the

music—those qualities which, above all others, Sviatoslav Richter serves

so well in his Schumann playing. I shall return more often, I think, to

the Beethoven side of the record, which has an authority only Schnabel

at his best could equal.

S.P., The Gramophone, April 1967- excerpt

Review (Sonata No. 26)

If

Solomon's supple control is admirable in the " Moonlight ", in " Les

Adieux" it enables him to give a performance such as I have not heard

equalled. Foi this "programmatic" sonata (the Farewtll, the Absence, the

Meeting Again) is fiendishly difficult to hold together. In the

Backhaus and Novaes performances the opening Adagio disintegrates ; with

Solomon the basic pulse is beautifully sustained. In the Andante

espressivo, the Absence, the problems of varying motion are most

adroitly solved; and the Finale has an impetuosity, a joyful freshness,

such as may surprise some of Solomon's listeners. The recording, like

the performance, has no faults at all, but is entirely admirable. (The

Gulda version listed above is too poorly recorded to recommend.)

A point of detail: four bars from the end of the first movement Beethoven has marked a crescendo which baffles editors and which interpreters generally prefer to render as diminuendo. Solomon surprises us at first hearing by realising the sense of the marking; by the third hearing we are completely convinced.

On the strength of this disc it certainly seems as if Solomon's complete recording will become the "standard" one. H.M.V have shown no signs of giving Schnabel's discs a new, LP, lease of life; and Decca's Backhaus issues, as we have all been saying in these pages, are immensely variable. Perhaps it is worth remarking, what one tends to take for granted in Solomon's readings, that the performances are instinct with loving care. Backhaus sometimes gives the impression that he has simply sat down and played off the sonata. There is nothing like this about Solomon: the result is not a lack of freshness (one listens as if hearing the music for the first time), but an inimitable rightness.

A.P., The Gramophone, December 1954- excerpt

Classical CD Review review

From the opening bars and its skyrocket arpeggios, he designs the concerto to overwhelm the audience.

Vive l'empereur! Heil Waldstein! Pristine crosses the finish with a roar

in its final installment of Solomon's Beethoven piano concerto cycle. I

have worried in previous reviews that Solomon might not have the sufficient

vulgarity to play the Emperor. Of the cycle, probably my least favorite

(I'm perverse), it seems to move me only when a pianist fully commits to

its bombast. Solomon had struck me with his elegance and lyricism, two

qualities you can have too much of in certain works -- like this one, Beethoven's

essay in piano virtuosity. From the opening bars and its skyrocket arpeggios,

he designs the concerto to overwhelm the audience.

Solomon's hands give the concerto both interpretive sophistication and

plenty of mojo. Much of his ingenuity comes down to a perceptive judgment

of what to leave to the orchestra. For example, in the intro's "rockets'

red glare," the orchestra launches the fireworks with a boom, while

Solomon lyrically comments, even managing a perfect diminuendo. Indeed,

during most of the first movement, the orchestra gives the "public

face" of heroism and Solomon the meditative one. Thus, when the pianist

takes the lead, the ramp-up makes all that much bigger a stir. Such contrast

rarely succeeds in general, since it can sound like orchestra and soloist

haven't found themselves on the same interpretive page. Here, however,

the collaboration between Solomon and Menges is so tight that the entire

movement seems conceived as an entirety, rather than as a bunch of "magic

moments," although you get plenty of those, particularly at the piano "scintillation" of

the B theme.

Menges's opening to the second movement convinces me of his greatness

as a Beethoven conductor as he perfectly captures the elusive simplicity

of

the Beethoven "spiritual" chorale. Solomon glides in after

him, smooth as a swan on a lake, with that kind of stillness. The singing

could

easily bog down, but both performers keep up a gentle push. The transition

to the third movement yields the only disappointment in the entire concerto

-- too raggedy, the string plinks all over the place. They probably went

for an improvisatory effect, but the coordination broke down. However,

Solomon rebounds with his entrance, full-blooded and, considering his

previous restraint, the equivalent of a roar. Unlike many interpretations,

the entire

movement becomes simultaneously powerful and buoyant, which trades in

grandiosity for genuine grandeur.

For me, too many Emperors come cut from the same cloth, and I have little

to no reason to prefer one to another. A truly original, non-bizarre interpretation

you rarely run into. Solomon and Menges strike a unique balance between

Romantic ardor and classical mesure. In fact, it has begun to

push me toward a more complex view of both the concerto and Beethoven

in general. I think

of Beethoven as a composer of "edges" --abrupt transitions,

rough, sharp contrasts, and so on, at odds with a suave approach. Yet

Solomon

and Menges bring it off and, doing so, take off the curse of crude manipulation

from the score.

The first Beethoven piano sonata I ever heard neither the Pathétique or the Moonlight, the Waldstein knocked me on my tush and hasn't yet let

me up. Schnabel played, and his interpretation has remained my touchstone,

not only because I think it terrific but because I know it longest and

best. Briefly, Schnabel drives the first movement and creates a quasi-improvisatory

second which leads to a roller-coaster ride to the end of the third. The

Waldstein, one of the harder sonatas, leads Schnabel into his share of

splats. However, he plays as if in the grip of the thing, possibly because

he would run into outright disaster if he let go. Nevertheless, this grip

translates into a kind of obsession, which works for this sonata.

Technique is never Solomon's problem. The speed and clarity of his runs

amaze, and with a powerful, golden tone, besides. Furthermore, he takes

the fiendish first movement as fast as I believe I've ever heard it and

nails the tough parts (the octave fanfare idea, for example). He propels

the quick sections, beautifully relaxes in the lyrical ones. Unlike Schnabel,

he seems in complete control, avoiding the former's desperate vibe for

pure exhilaration. Conceptually, the second movement strikes me as the

most difficult, for it seems to reside in a half-way place between song

and recitative. Schnabel finds himself closer to recitative, Solomon to

song. The transition to the finale is tricky, although many pianists do

well enough, Solomon among them, but Schnabel really gets it. Once Solomon

hits the finale, he's at his best, paradoxically restrained in tempo and

headlong in rhythm. Lights and shades fill his phrases. This isn't all

hit-and-run. We get gorgeous diminuendos and crescendos as well as varieties

of touch and tone, from delicate to muscular, but it avoids the precious,

as the coda's speed-up amply demonstrates.

I'm currently cooling off toward the Les Adieux sonata, although I recognize

it as one of Beethoven's most radically-conceived sonatas, proceeding on

drama and mood rather than on pure structure, the sonata equivalent of

the Pastorale Symphony. In three movements -- "Farewell," "Absence," and "Reunion," it

commemorates Beethoven's friend and patron's, Archduke Rudolph, escape

from Vienna as Napoleon's armies approached the city and the archduke's

eventual return. "Farewell" is tender, "Absence" rolls

in misery, and "Reunion" gets giddy. For me, the work anticipates

Wagner. My failure to respond may come down to the fact that I've listened

to it too many times after the Waldstein. Scores go in and out all the

time for me, so I'm fairly confident that one day I'll hook into it again.

Whatever my indifference to the score, it doesn't stem from Solomon, who

delivers one of the most beautiful Les Adieux I've heard. Again,

one notes the balance between Classical restraint and Romantic ardor. "Absence" is

most affecting, while "Reunion" is practically pure rush.

All these recordings are mono, but they come from the tail of Solomon's

career -- early to mid-Fifties -- so the bases are actually pretty good,

especially that of the Emperor. Pristine aims

not only to clean up noise and recording vagaries but to produce as good

a sound as possible -- to

get the most music out of the grooves. It has applied its XR "ambient

stereo" recording process, which I find misnamed. It doesn't produce

a left-right distribution, unlike the horrors of electronic stereo, but

rather emphasizes the ambience of the recording, "rounds out" what

you hear -- a "front-to-back" enhancement. A beautiful disc.

S.G.S. (March 2014)