This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Review

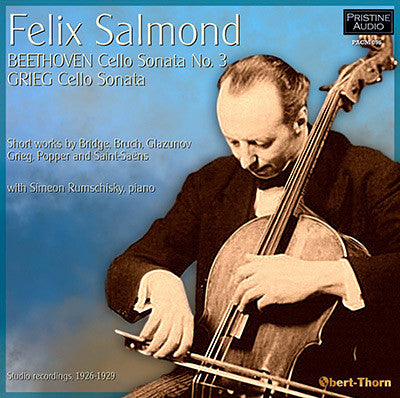

Felix Salmond, influential and inspirational English cellist, plays Beethoven, Grieg and more

""they have struck immediately the right mood for each movement and never lost sight of it amid the mass of detail" - The Gramophone

British cellist Felix Salmond (1888-1952) was born into a musical family. His father was a baritone and his mother a pianist who had studied under Clara Schumann. He began formal cello studies at the age of 12, entered the Royal Academy of Music at 16 and went on to study at the Brussels Conservatory at 19. The following year, he made his debut at Bechstein Hall in London, in a program which included Frank Bridge’s Fantasy Trio with the composer as violist and Salmond’s mother at the piano.

Salmond’s attempt to build an international career was interrupted by World War I. After its conclusion, he participated in the first performance of Elgar’s String Quartet. As a result, Elgar chose him to give the première of his Cello Concerto under the composer’s direction in 1919. The performance turned out to be a debacle. Albert Coates, who was conducting the rest of the concert, used up most of Elgar’s scheduled rehearsal time, leading the angered composer to consider withdrawing the work. For Salmond’s sake, he went on with the performance; but the critics savaged the orchestra’s poor execution. Wounded by the experience, Salmond would never play or teach the concerto outside of England. In 1922, he left for America, which would become his home base for the rest of his life.

It was perhaps as a pedagogue that Salmond left his most enduring

legacy. He began teaching at Juilliard in 1924, where he stayed until

his death, and was appointed head of the cello department at the Curtis

Institute the following year (a post from which he abruptly resigned in

1942 when the Institute’s new director, Efrem Zimbalist, engaged Emanuel

Feuermann to join the faculty without having consulted Salmond). His

pupils included Leonard Rose, Bernard Greenhouse, Frank Miller, Alan

Shulman, Daniel Saidenberg and Orlando Cole.

Salmond’s discography is comparatively small. After a few acoustic Vocalions made in England before his emigration, he was signed by American Columbia, where he benefitted from the recent defection of their star cellist, Pablo Casals, to the rival Victor label. This release presents most of his electric commercial recordings, which ended in 1930, even though he was to continue performing for another two decades. It features two of the three album sets that Columbia issued, the third being the Schubert B-flat Piano Trio with Myra Hess and Jelly D’Aranyi (Pristine PACM 083).

The present transfers were made from first edition American Columbia “Viva-Tonal” pressings, the quietest form of issue for these recordings. Some of the tracks, particularly the earliest ones, suffer from distant miking and have an inherently smaller signal-to-noise ratio than others.

Mark Obert-Thorn

-

BEETHOVEN Cello Sonata No. 3 in A major, Op. 69

Recorded 18 January and 16 February 1926 in New York City

Matrix nos.: W 98207-3, 98208-1, 98209-3, 98210-1, 98225-3 & 98239-1

First issued on Columbia 67187-D through 67189-D in Set 38

• BRUCH: Kol Nidrei, Op. 47

Recorded 5 and 17 June 1928 in New York City

Matrix nos.: W 98550-1 & 98551-3

First issued on Columbia 50073-D• TRADITIONAL (arr. O’Connor-Morris): Londonderry Air

Recorded 15 February 1926 in New York City

Matrix no.: W 98240-1

First issued on Columbia 7107-M• SAINT-SAËNS: The Swan (from Carnival of the Animals)

Recorded 15 March 1926 in New York City

Matrix no.: W 98242-3

First issued on Columbia 7107-M• GLAZUNOV: Serenade Espagnole, Op. 20, No. 2

Recorded 19 April 1926 in New York City

Matrix no.: W 98234-5

First issued on Columbia 7117-M• BRIDGE: Mélodie

Recorded 20 May 1929 in New York City

Matrix no.: W 98660-2

First issued on Columbia 50156-D• POPPER: Gavotte in D major

Recorded 15 June 1928 in New York City

Matrix no.: W 98553-2

First issued on Columbia 50156-D• GRIEG: To Spring, Op. 43, No. 6

Recorded 25 October 1927 in New York City

Matrix no.: W 98401-6

First issued on Columbia 67363-D in Set 78

-

GRIEG Cello Sonata in A minor, Op. 36

Recorded 13 and 17 May 1927 in New York City

Matrix nos.: W 98345-3, 98346-2, 98347-1, 98348-1, 98349-2, 98350-3 & 98351-4

First issued on Columbia 67360-D through 67363-D in Set 78

Felix Salmond cello

Simoen Rumschisky piano

Beethoven Cello Sonata No. 3 (original 78rpm issue)

Beethoven’s Sonata in A for ’cello and piano, op. 69, was down on the list of works to be done by Columbia for the Beethoven centenary. Whether it actually appeared with the rest of the centenary records I cannot say, but in any case it is only now that the discs have reached me. The Sonata occupies six sides (L. 1935—7, three 12in. records, 19s. 6d.) and is admirably played (complete, of course) by Felix Salmond and Simeon Rumschisky. The ’cello Sonatas are probably less familiar to most people than those for piano or for violin, but they form nevertheless a distinguished series in which the A major stands out much as the Kreutzer does among those for violin or the Appassionata among the piano works. It is, that is to say, a good example of Beethoven’s “ middle period ” at its best, and as it is the middle period that has found most favour with the general public Columbia have done wisely in selecting it for recording. The broad, spacious first movement and the characteristic Scherzo are on the usual Beethoven plan. But the slow movement after a promising start is suddenly abandoned (as happens also in the Waldstein) and we pass at once to the brilliant Finale. The performers are fully competent technically to tackle what is by no means an easy work, and they deserve high praise for the manner in which they have struck immediately the right mood for each movement and never lost sight of it amid the mass of detail. The “ brassy ” quality of the Columbia ’cello tone, concerning which I have previously complained in these pages, has not quite disappeared, but it is far less marked than it was, and is confined to a few loud passages in the tenor register. Elsewhere and in other respects I found nothing to criticise and a great deal to admire. The work presents some difficult problems of balance, especially perhaps in those passages where the ’cello part lies very low and the piano is busy above it. But all these have been successfully negotiated, and we have on the whole a set of records worthy to rank with the other Columbia centenary issues. I can offer no higher praise.

P.L.

The Gramophone, September 1927

Fanfare Review

A robust-, rich-, and vibrant-toned player

British-born Felix Salmond (1888–1952) was a distinguished cellist and later a highly regarded pedagogue at Juilliard and Curtis. Unfortunately, through no fault of his own, his performing career was seriously tarnished, perhaps even sidelined, due to the disastrous London premiere of Elgar’s Cello Concerto in 1919, in which Salmond had been personally entrusted by the composer with the solo part. Elgar, who conducted the performance, had been given little time to rehearse, and the critics were merciless in their morning-after reviews.

Though he was in no way responsible for the debacle, Salmond was thereafter dogged by it in the UK, so in 1922, he crossed the Pond, made his New York debut, and settled in America. Two years later he joined the faculty at Juilliard, and a year after that he was appointed head of the cello faculty at the Curtis Institute of Music, a position he held until 1942, when he abruptly resigned in a snit over being snubbed by the institute’s new director, Efrem Zimbalist, who had hired Emanuel Feuermann without consulting Salmond.

Mark Obert-Thorn, who remastered and produced these recordings for Pristine, has written a bio of Salmond that is close to a verbatim extract from Wikipedia’s entry on the cellist. There’s nothing wrong in that, except that in cutting and pasting, Obert-Thorn seems to have gotten some of the wording out of order, with a highly amusing result that deserves quoting: “It was perhaps as a pedagogue that Salmond left his most enduring legacy. He began teaching at Juilliard in 1924, where he stayed until his death, and was appointed head of the cello department at the Curtis Institute the following year….” There’s nothing like a little post-mortem moonlighting to ward off the eternal boredom.

To set matters straight, Salmond was at Juilliard for only a short time before taking the position at the newly established Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, where, it’s true, he remained until he resigned in 1942 over the Feuermann affair. But as you can see from Salmond’s dates given above, he lived another 10 years until 1952. If only he’d not let his bruised ego dictate his precipitous actions, he might have stayed on at Curtis until the end, for Feuermann’s tenure there was very brief, less than a year, in fact. He died suddenly in 1942 at the age of 39 from complications following a surgical procedure. So, out of pique, Salmond had given up a good job and prestigious position for nothing, though he probably took some personal pleasure in seeing Zimbalist left twisting in the wind.

Among the students Salmond taught at Curtis, while dead according to Obert-Thorn, were Leonard Rose, Bernard Greenhouse (of Beaux Arts Trio fame), and Frank Miller, who played under Toscanini in the NBC Symphony Orchestra and recorded Strauss’s Don Quixote with the maestro for RCA in 1953.

I’m not quite sure how prominent a pedestal Salmond occupies in the Cello Hall of Fame. His dates place him relatively close to Pablo Casals (1876–1973), Guilhermina Suggia (1885–1950), Beatrice Harrison (1892–1965), and Gaspar Cassadó (1897–1966), of those who were born in the 19th century and lived far into the 20th.

I don’t believe Salmond recorded very extensively, though he did make a handful of 78s for Columbia, mainly in the late 1920s. Mark Obert-Thorn has put together this program from a number of those Columbia recordings, all made in New York between 1926 and 1929. There’s no point in pretending the sound on this CD will have you marveling at how great it is. There’s considerable grit in the grooves, which manifests itself as a kind of constant low-grade swooshing background noise, like the cosmic radiation residue from the Big Bang.

If you can get past that, Salmond comes across as a robust-, rich-, and vibrant-toned player—it’s easy to hear the influence he had on Leonard Rose—and as having a strong, confident technique. His big-ticket numbers on the disc, the Beethoven and Grieg sonatas, would be absolutely competitive in today’s market if the recordings were up to current state-of-the-art standards.

With the exception of Bruch’s Kol Nidrei, the remaining items on the disc fall into the category of short salon and encore-type pieces, all of which Salmond favors with his radiant, rotund tone. He’s placed forward and spotlighted, so that Simeon Rumschisky’s piano sometimes seems banished to a faraway place, but Rumschisky is no shrinking violet. He holds his own and proves himself an essential contributor to these performances.

As always, Pristine’s releases are available direct from pristineclassical.com as physical CDs as well as downloadable files in mp3 and FLAC formats. The current offering is well worth your attention, if great cellists and cello playing of the past interest you. Jerry Dubins