This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Cast Listing

- Cover Art

- Sleevenotes

- Contemporary Review

Miss Sutherland's Rodelinda is on

a level with her Lucia—confirmation that we have in our midst one of the

great sopranos of the world. The brilliance and beauty of her coloratura

are matchless. But no less notable is the exquisitely drawn phrasing of the

slow melodies and of the recitative, the subtle and intricate line and play

of tone-colours by which she gives to Handel’s music such meaning and

eloquence. With one aria in particular in the last act, in prison when she

believes her husband has been slain, she ravished the ear and melted the

heart: but it is perhaps unfair to single out just one passage when the

role, a magnificently rewarding one, offered so many treasures. - Opera, 1959

Handel's Rodelinda was one of three operas revived in London in 1959 for the Handel bicentenary. It received just two performances at Sadler's Wells - happily including a live BBC broadcast from the theatre. Whilst this broadcast has surfaced before, on an Italian release from the mid-1990s, the quality of that release was poor, with limited sound quality, wobbly pitch, and other shortcomings.

By contrast the sound quality here is superlative almost throughout. Drawn from exemplary transfers of high quality FM tape recordings, the present release offers a vast improvement over the previous issue if you've heard it, and a delight to the ears if you have not. It was in performances like this that the Joan Sutherland legend was born - and cast alongside such fabulous singers as Janet Baker and Raimund Herincx, this really is any opera-lover's delight.

I should however point out that a number of patches have been necessary: a handful of very short sections to cover tape changes are almost impossible to detect, lasting in some cases no more than a fraction of a second. However some damage to the primary source tape during Act 2 forced me to resort to a secondary source of lesser quality in a handful of places. I have done as much as possible to match the sound of these to that of the main source, but the sonic limits of this secondary source may become audible at times. Nevertheless the bulk of the second act and all of the first and final acts retain the full, excellent quality of the original source.

Andrew Rose

HANDEL Rodelinda

Raimund Herincx - Garibaldo

Janet Baker - Eduige

Margreta Elkins - Bertarido

Alfred Hallett - Grimoaldo

Patricia Kern – Unulfo

Philomusica of London

Continuo: Thurston Dart, harpsichord

conducted by Charles Farncombe

XR remastering by Andrew Rose

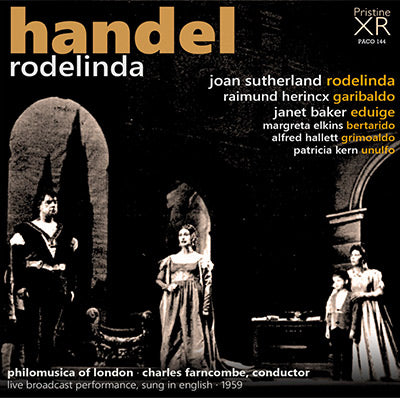

Cover artwork based on a photograph of the performance

Broadcast on 24 June 1959

Sadler's Wells Theatre, London

Sung in English

Translation by David Harris

Track titles shown in the original Italian to aid navigation, comparison and score-following

Total duration: 2hr 15:26

The bicentenary of Handel’s death and the tercentenary of Purcell’s birth were marked in London in June 1959 by a three week festival of their music. London was an obvious place to hold it: both composers had worked there, and indeed both are buried in Westminster Abbey. Four of Handel’s operas were performed during the festival: Samson at Covent Garden,Rodelinda and Semele at Sadler’s Wells, and Solomon at the Royal Festival Hall.

Rodelinda was written in 1725 for the King’s Theatre, Haymarket but was not heard in Britain between the eighteenth century and a radio performance in 1928. A different radio performance followed in 1935, and finally there was a revival at the Old Vic in 1939. This 1959 production thus brought a rarely heard opera to London audiences.

The star of this production was undoubtedly Joan Sutherland. Sutherland had begun the move from dramatic soprano to dramatic coloratura, specialising in previously obscure bel canto operas, with Handel’s Alcina in March 1957. Handel’s Samson and Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor had followed in late 1958 and early 1959. She takes the title role in this performance, an ideal vehicle for her dazzling coloratura. The reviewer in the Times described her performance as ‘momentous in beauty and dignity, pathos and electric vigour,’ while Opera Magazine saw the performance as ‘confirmation that we have in our midst one of the great sopranos of the world.’

Janet Baker sings Eduige in what could easily be called her break-through performance. Aged just 25 at the time, she went on to become Britain’s leading mezzo-soprano with a particular affinity for the bel canto repertoire. Her recordings of the works of Bach, Gluck, Handel and Purcell became benchmarks. Janet Baker was actually a far more versatile singer than that, performing works as diverse as the Trojans by Berlioz, Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde, and Britten’s Owen Wingrave. She was also a regular and notable recitalist. Opera Magazine described her as ‘one of the most arresting, intelligent and imaginative mezzos we have, with vivid declamation and a rich, ringing, individual timbre.’

Grimoaldo is sung by the British bass-baritone Raimund Herincx. Aa a house baritone for Welsh National Opera and Sadler’s Wells, Herincx proved himself capable of singing a wide variety of roles and genres, from Verdi to Tippett. Later in his career he became best known for Wagnerian roles.

Conductor Charles Farncombe created the Handel Opera Society in 1955, with the aim of restoring Handel’s forgotten operas to the stage. His production of Deidamia in 1955 received a positive audience response, and a regular series of opera productions ensued, often at Sadler’s Wells. This BBC broadcast is an important addition to his rather small discography.

With Callas singing Medea at Covent Garden, and Joan Sutherland singing Rodelinda at Sadler’s Wells, the London summer season was indeed starry. The only pity is that Rodelinda was done only twice: it would be sad if neither Sadler's Wells nor Covent Garden could see its way into taking over this Handel Opera Society production for some further performances. In 1959 there is no longer need to begin by expressing surprise that—contrary to all the textbooks—Handel’s operas, with da capos, castratos. artificial plots and all, should prove stageworthy. The Germans have known it for years, and thanks to the work of the Handel Opera Society, most opera-loving Britons (the directors of our national theatres of course excepted) know it too. Here is a rich heritage of opera hardly explored by the nation for whom it was written. (To hear Miss Sutherland's superb Alcina again, it looks as if we shall all have to go over to Cologne.) These British Handel performances score over the German ones in that Charles Farncombe does not transpose major roles down an octave, but finds a seemingly endless supply of mezzo-sopranos and contraltos to don with distinction the castrato breeches. Also, he does not tinker with the orchestration, but allows Handel’s extraordinary tone-colours to sound as the composer intended.

Reason tells us that the dramatic oratorios are more perfect works of art than the operas—that the plots are finer, the musical spans more sustained, and on a nobler level altogether. But anyone who loves the conventions of opera must capitulate utterly when Alcina or Rodelinda is offered him. Aria follow's glorious aria, poured out like jewels from a treasure hoard. The invention is endless, and constantly astonishing. The music is impassioned, or meltingly beautiful. And. though the situations (like those of II Trovatore, or Forza, or La Gioconda) are contrived, the characterization rings deep and true. Rodelinda, like Fidelia, is a tale of married love, of constancy and courage in adversity. As Winton Dean says well, ‘Handel expresses every facet of conjugal emotion—separation, longing, despair, hope, relief—in music of marvellous eloquence.’ But beyond this it is a nicely complicated, intricate and interesting plot. There is a Machiavellian intriguer (bass), who has betrayed Bertarido, King of Lombardy, and now seeks to betray the usurper he helped to the throne. The heroine has a sister-in-law, Eduige (mezzo), with some vivid arias. Bertarido’s faithful courtier. Unolfo (comprimario castrato), has some fine forthright little arias too. The usurping Grimoaldo (tenor), after his villainous set-pieces, is allocated a scena of rare beauty in which remorse assails him, and he envisages the lot of a shepherd.

As with all the operas, the music of Rodelinda implies far more brilliant singing than that of the oratorios: and a highly distinguished cast was assembled for this performance. Miss Sutherland's Rodelinda is on a level with her Lucia—confirmation that we have in our midst one of the great sopranos of the world. The brilliance and beauty of her coloratura are matchless. But no less notable is the exquisitely drawn phrasing of the slow melodies and of the recitative, the subtle and intricate line and play of tone-colours by which she gives to Handel’s music such meaning and eloquence. With one aria in particular in the last act, in prison when she believes her husband has been slain, she ravished the ear and melted the heart: but it is perhaps unfair to single out just one passage when the role, a magnificently rewarding one, offered so many treasures. Miss Sutherland's acting was also marked by the tenderness and the fire which distinguished her Lucia: expression, gesture and bearing were always such as to enhance the music.

There were three other distinguished singers in the cast. Janet Baker (Eduige) is one of the most arresting, intelligent and imaginative mezzos we have, with vivid declamation and a rich, ringing, individual timbre. Margreta Elkins (Bertarido), another truly 'operatic’ mezzo, was particularly artistic in her singing of the lovely ‘Dove sei,’ and of the garden air (one with flutes both transverse and à bec). The entrancing duet in which she and Miss Sutherland take a farewell as tender as Belmonte's and Constanze’s must also be mentioned. And Raimund Herincx (Garibaldo, the intriguer) sang as strikingly as befits one of our most stylish bass-baritones.

Alfred Hallet (Grimoaldo) and Patricia Kern (Unolfo) were both effective, though not quite on this exalted level. Mr Farncombe again showed a thorough understanding of Handel, and managed both the dramatic and the lyrical passages with equal success. The Philomusica played well. And Anthony Besch is a master of the difficult art of staging opera seria so as to convince a modern audience. Eschewing the German tricks of fussification and busy “invention” to take our minds off the da capos (who could want distraction, when these were so beautifully sung, and adorned with new surprises!), presented the drama in a dignified way. There was one modern trick, but that a clever one: during introductory ritornellos, Mr Besch held our attention on the stage picture by keeping us guessing for a while who was due to sing the next aria. Robin Pidcock’s settings missed any very distinctive style, and the out-of-perspective cemetery scene betrayed an inexperienced hand. The prison, however, was most effective. They were pleasant, open, and undisturbing. It remains only to mention a first-rate English translation by David Harris which lies on the music convincingly and never breaks idiom.

A.P ., Opera magazine, August 1959