This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

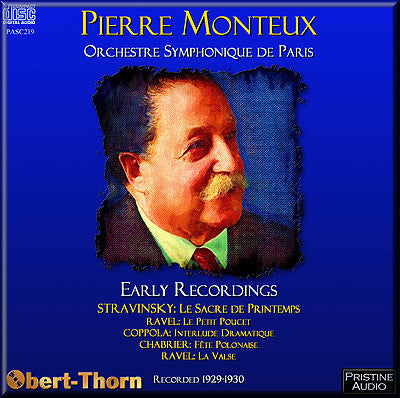

- Cover Art

Rare early recordings, including a complete 1929 Rite of Spring

Pierre Monteux "bracing" in Stravinsky, Ravel, Chabrier and Coppola

Pierre Monteux’ early recordings fall into three general categories: the Berlioz discs, including a complete Symphonie Fantastique; the three concerto recordings with Menuhin; and the rest, which are presented here. While the Menuhin recordings have rarely been out of print in one form or another since they first appeared and the Berlioz records have seen at least two CD reissues during the 1990s, the remainder have proven rather hard to come by. I am aware of only one previous CD reissue of the Stravinsky, Coppola and Chabrier items, and none at all of the two Ravel works.

Part of the reason for this may have been due to the rarity of the original discs. Unlike the Menuhin recordings, which saw release throughout the world, or the Berlioz records which came out in America, the other recordings were only issued in France. Adding to their rarity are the difficulties involved in their transfer. None of them were released on particularly quiet shellac, and much of the original engineering was not state-of-the-art for the time. The volume levels of several of the recordings were adjusted downward as the recordings went along, requiring compensating increases on the part of the restoration engineer; and the recorded sound is sometimes rather raw and harsh.

Most problematic of all is Monteux’ first recording, the Stravinsky. Four of the eight sides were only issued as sonically-compromised “dubbings”. These were re-recordings made from the original metal discs or shellac pressings in order to decrease volume levels so that the discs would pass the “wear test”, particularly needed for the many loud passages in this work. Being copies of copies, dubbings had inherently inferior sound. They also had similar volume decrease problems, which I have attempted to mitigate by matching the dynamic extremes against Monteux’ 1956 Decca recording with the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra.

Notwithstanding their many faults, these are bracing performances. It is a particular shame that La Valse and Sacre did not see the international release that the contemporaneous recordings by Koussevitzky and Stokowski had in the Victor/HMV family of labels, because in both scores Monteux proves more vital than the other conductors’ comparatively restrained accounts. La Valse in particular has a wealth of characterful detail in the wind playing, coupled with an inexorable momentum that carries through to a shattering conclusion.

Mark Obert-Thorn

-

STRAVINSKY: Le sacre du printemps

Recorded 23rd – 25th January, 1929 in the Salle Pleyel, Paris

Matrix nos: CS 3172-1T1, 3175-1, 3176-1T1, 3177-2, 3178-2, 3186-1T1, 3173-2T1, and 3174-3

First issued on Disque Gramophone W-1008 through 1011

-

RAVEL: Le petit poucet (Ma mère l’oye)

Recorded 3rd February, 1930 in the Salle Pleyel, Paris

Matrix no.: CF 2842-2

First issued on Disque Gramophone W-1108

-

COPPOLA: Interlude dramatique

Recorded 3rd February, 1930 in the Salle Pleyel, Paris

Matrix nos.: CF 2849-2 and 2850-1

First issued on Disque Gramophone W-1108

-

CHABRIER: Fête Polonaise ( Le Roi malgré lui)

Recorded 29th January, 1930 in the Salle Pleyel, Paris

Matrix nos.: CF 2818-2 and 2819-1

First issued on Disque Gramophone L-796

-

RAVEL: La valse

Recorded 31st January, 1930 in the Salle Pleyel, Paris

Matrix nos.: CF 2839-3, 2840-1 and 2841-2

First issued on Disque Gramophone W-1107 and 1108

Pierre Monteux · Orchestre Symphonique de Paris

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Pierre Monteux

Total duration: 62:27

Fanfare Review

Recalling the first time he heard Le sacre du printemps when Stravinsky played it for him on the piano, Pierre Monteux admitted, “I must admit I did not understand one note of Le sacre du printemps. My one desire was to flee that room and find a quiet corner in which to rest my aching head.” Given the initial reaction of the conductor who eventually led the premiere, is it surprising that many in the first-night audience found the piece baffling? One of the players in Diaghilev’s orchestra said he believed that some of the hostility was directed at Nijinsky’s choreography, which seems to have resembled calisthenics more than dancing. In any event, while Monteux was resting his “aching head,” Diaghilev turned to him and said, “This is a masterpiece, Monteux, which will completely revolutionize music and make you famous because you are going to conduct it.” In fact, Monteux ended up making suggestions about altering some of the orchestration, which Stravinsky followed.

Obviously, a recording, even if made nearly 16 years later, by the conductor who led the premiere has an obvious interest. Fortunately, we need not be satisfied with the dim sound of this 1929 effort, since Monteux went on to record the music three more times and there are many “unofficial” recordings as well since Monteux, like it or not, could not escape his association with Le sacre du printemps; in a way, Diaghilev was right. Obviously, it would be unfair to compare this pioneering effort with his later ones; what I did was measure it against Stravinsky’s first recording of the piece, made five months later with the Straram Orchestra (billed, for contractual reasons, as “symphony orchestra”). Given the absence of dancers, I wonder if the 1913 performance went at this tempo. I do not mean to suggest that this a particularly fast performance since it isn’t, but recordings suggest that experienced ballet conductors often have a tendency to speed up when freed from the needs of the choreographer and his dancers.

In part 1, the original 78 surfaces are noisy but one adjusts to it. The winds are dimmer than usual and more distant. I suggest that listeners turn up the volume to enhance the experience. The timpani are muffled though clearer than they are on Stravinsky’s recording. In fact, this is the better of the two recordings in every way, for Monteux is obviously the more proficient conductor and has been more fortunate in his technical team. Nevertheless, the recording exposes or emphasizes some odd details that one may not have noticed in “better” recordings and the 78s used for part 2 seem to have had better surfaces. Monteux starts part 2 at a slower tempo than Stravinsky, obtaining a more mysterious atmosphere, but tempowise, there are not radical differences between him and the composer. I don’t regularly deal with Stravinsky’s music here, though I have been acquainted with it for years, so I’ll use this review to point out that, if I were looking for a “modern” recording, I would not choose one by Monteux or Stravinsky, though both have given us perfectly good ones. My choices would be Igor Markevitch’s mono and stereo recordings with the Philharmonia Orchestra (coupled on Testament), Markevitch’s with the London Symphony Orchestra, James Levine and the Met Orchestra, and Antal Doráti’s mono recording with the Minneapolis Symphony. That last one has, fortunately, been issued under “pirate” auspices and is well worth investigating.

Maybe better copies of the other pieces on the CD were available, for what one hears on the rest of the CD is what one has come to expect from the best modern transfers—amazingly vivid sound, in this case, from 78s recorded in 1930. Monteux was the first conductor to record the entire Mother Goose ballet with the pieces in the correct order, including the interludes between them. It might have been interesting to hear how he would have done it in 1930 but all we have here is one movement, Petite Poucet, with the solo winds close and clear. The fact that Piero Coppola was an A & R man as well as a conductor and composer may have had a lot to do with Monteux’s recording of his Dramatic Interlude, a motor-driven piece in which Coppola demonstrates his mastery of the language of the great Hollywood composers of the ’30s and ’40s. It’s no trial to listen to and you might even come back for more if your tastes lie that way. The Chabrier is a vigorous, lilting performance—quite wonderful, though I wonder if its liveliness had anything to do with the length of the 78 sides. One might have similar questions about La Valse, which zips along pretty fast as well, but it’s actually similar to his later ones and speed does not preclude rhythmic flexibility (with Monteux, it never did).

James Miller

This article originally appeared in Issue 34:1 (Sept/Oct 2010) of Fanfare Magazine.