This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Additional Notes

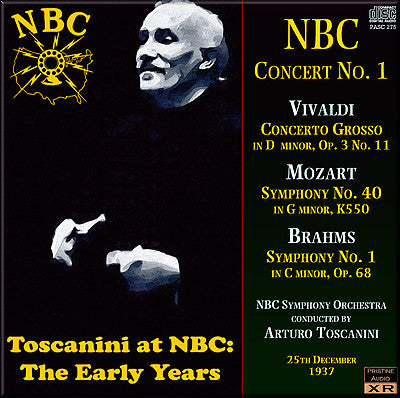

Toscanini's NBC Symphony Orchestra debut concert

The start of a beautiful friendship - now XR remastered

This first ever broadcast by Toscanini and the orchestra created for him by NBC radio is presented here in its entirety, including all preserved applause and announcements. This decision was made both on historic grounds and also because the musical content alone was slightly too long for a single CD issue.Sonically the concert is reasonably well preserved for a broadcast of its vintage, and though I have had to battle for long sections an almost ever-present disc surface noise, it is a battle that has largely been won. As well as a full XR remastering filling out the original, highly constricted sound considerably, I also took the opportunity to soften the hard 8H acoustic with a touch of convolution reverberation, using the perhaps appropriate acoustic one finds in the concert hall at La Scala, Milan.

Andrew Rose

-

VIVALDI Concerto Grosso in D minor, Op. 11 No. 3

Mischa Mischakoff, violin

Edwin Bachman, violin

Oswaldo Mazzuchi, cello

-

MOZART Symphony No. 40 in C minor, K550

- BRAHMS Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68

NBC Symphony Orchestra

conductor Arturo Toscanini

Full concert programme as broadcast, 25th December 1937

Broadcast from Studio 8H, NBC Radio City, New York

Introduced by Howard Claney

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, February 2011

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Toscanini

Total duration: 1hr 34:09

REVIEWS:

"The presentation of senior Toscanini and a superlative orchestra as its contribution to the world on Christmas night was a high pinnacle for radio for which the National Broadcasting Company is entitled to handsome appreciation. Musically it was an even of the most obvious importance. The departmental specialists are appraising its technical merits and magnitudes in expert terms, but it also is a milestone in the radio's social development because here a broadcasting network seized on the thing it could do best and proceeded to do it in the finest and most dignified and useful way... The performance stands for a thousand irritations of the radio for which it atones, and the public today can look forward gratefully to nine further Toscanini concerts in this great series." Editorial, The New York Telegram, December 1937

"When Toscanini and his magnificent National Broadcasting Company Orchestra finished the concluding strains of the Brahms First on Saturday night, the hearts of the music critics present in the audience were very full indeed. The reviews the next morning has the hushed tones of those who had seen the corner of the veil which hides the central mystery of music lifted. It was, several of them said, the experience of a lifetime. So it was, and what interests us is that this experience of a lifetime was shared by at least 20 million persons in America and many millions abroad. What interests us is that the Toscanini broadcast had been looked forward to for a good eight months, and it was the biggest item of news Saturday night and outweighed our last note to Japan in general conversation, that it brought listeners to the loudspeaker who had never willingly tuned into a symphony before, that the country is still talking about it.

But Toscanini has been a conductor for fifty years. There is therefore something odd and exciting in this rediscovery of something we have had for a long time. Suddenly a nation, pictured in the sniffy periodicals as clustered about the loudspeaker to hear 'The Moon Come Over The Mountain' gathers to hear Mozart and Brahms and to talk about it. Is this one of those moments of realisation that make artistic history? One of those pivotal points of popularisation? One of those accidents of publicity that may have permanent result? We think so, somehow. The National Broadcasting Company may have built better than it knew." Editorial, The New York Evening Post, December 1937

I was a violinist in that orchestra, and we were awaiting the first appearance of our conductor. There was no audience. The men, instruments in hand, sat nervously rigid, scarcely breathing. Suddenly, from a door on the right side of the stage, a small, solidly built man emerged. Immediately discernible were the crowning white hair and impassive, squat, high-cheekboned mustached face. He was dressed in a severely eut black alpaca jacket, with a high clerical collar, formal striped trousers, and pointed, slipperlike shoes. In his hand he carried a baton. In awed stillness we watched covertly as he walked up the few steps leading to the stage.

As he stepped up to the podium, by prearranged signal, we all rose, like puppets suddenly propelled to life by a pent-up tension. We had been warned in advance not to make any vocal demonstration and we stood silent, eagerly and anxiously staring.

He looked around, apparently bewildered by our unexpected action, and gestured a faint greeting with both arms, a mechanical smile lighting his pale face for an instant. Somewhat embarrassed, we sat down again. Then, in a rough hoarse voice he called out, "Brahms!" He looked at us piercingly for the briefest moment, then raised his arms. In one smashing stroke, the baton came down. A vibrant sound suddenly gushed forth from the tense players like blood from an artery.

With each heart-pounding timpani stroke in the opening bars of the Brahms First Symphony his baton beat became more powerfully insistent, his shoulders more strained and hunched as though buffeting a giant wind. His outstretched left arm spasmodically flailed the air, the cupped fingers pleading like a beseeching beggar. His face reddened, his muscles tightened, eyes and eyebrows constantly moving.

As we in the violin section tore with our bows against our strings, I felt I was being sucked into a roaring maelstrom of sound—every bit of strength and skill called upon and strained into being. Bits of breath, muscle, and blood, never before used, were being drained from me. Like ships torn from their mooring in a stormy ocean, we bobbed and tossed, responding to these earnest, importuning gestures. With what a fierce new joy we played!

Playing with Toscanini was a musical rebirth. The clarity, intensity, and honesty of his musical vision—his own torment—was like a cleansing baptismal pool. Caught up in his force, your own indifference was washed away. You were not just a player, another musician, but an artist once more searching for long forgotten ideals and truths. You were curiously alive, and there was a purpose and self-fulfillment in your work. It was not a job, it was a calling.

From "This Was Toscanini" by Samuel Antek & Robert Hupka (Vanguard, 1963)