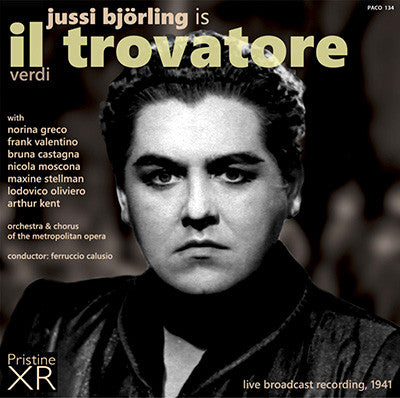

Björling's classic 1941 Met Opera Il Trovatore

"This is a great Il trovatore with one of the 20th-century’s great tenors - Fanfare

We return to our small but (almost)

perfectly preserved cache of fabulously-preserved NBC Metropolitan Opera

broadcasts from the early 1940s with this incredible performance of

Verdi's Il Trovatore, broadcast live from the opera house on the afternoon of Saturday January 11, 1941.

John H. Haley's wonderful CD notes (see tab) describe far

more eloquently than I could why this is one of the all-time greatest

recordings of the opera, and so I'll keep to making a few technical

observations on the recording itself.

As with other recent Met recordings

issued on Pristine, I've been given access to previously unheard (and

barely played) high quality 33rpm acetate disc records of the NBC

broadcast, made either in house or down a high quality line, as opposed

to off air. The original records included lengthy introductions and

intra-act discussions and talks which together added almost another full

hour to the proceedings, and have accordingly been cut from this

release - I've instead opted to leave an edited flavour of Milton

Cross's presentation at the beginning and end of the opera and as

appropriate within the recording. Fascinating as the discussion may have

been to historians I felt they would be superfluous to the performance

and the majority of latter day listeners.

As is common with vintage acetate

discs, it is the openings of sides which take the most punishment from

even a small number of replays, and that was the case here, where I've

had to deal with short sections of unwanted surface noise intrusions.

Thereafter, and for the vast bulk of the opera, the discs were in near

mint condition, with a remarkably wide frequency range and low noise

floor, making for some remarkably good sound quality for any recording

of this era. There is some treble loss to the end of sides but again

this is barely noticeable more than perhaps once, where I've taken steps

to disguise the change-over.

XR remastering has added another layer of life, body and

realism to the sound, with Ambient Stereo processing once again adding

just a hint of space and air around the central mono sound. The sample

features three of the best-loved arias from the opera and more than

adequately demonstrate just how good the performances and sound quality

are throughout this fabulous recording.

Andrew Rose

IL TROVATORE AT ITS BEST

By John H. Haley

One of the conventions with virtually all 19th century

operas is that we--the audience--must learn to accept the incongruity of

hearing large mature voices, often possessed by large, mature people,

portraying very young leading men and women on stage. Operas may be

drama but they are also comprised of demanding music, and the music must

be well served by performers who have the means to do so, or the

dramatic experience will almost always go for little.

We really do not want to hear a fifteen year-old girl attempt to perform Madama Butterfly,

and the best we can hope for is that the chosen soprano has found a way

to portray youthfulness, both vocally and visually. The same can be

said for the heroine in Strauss’ Salome and any number of other operas. And of course the great 19th and 20th

century opera composers did not create their grand works for immature

voices, clearly anticipating maturity of the both the performers’

artistry and their vocal means. Listening to an operatic recording, we

are greatly assisted by the “theater of the mind,” yet the particular

qualities of the vocal portrayals still play a large part in our

personal recreation of the drama that is screening in our heads as we

are listening.

Verdi always paid enormous attention to the dramas that formed the

basis for his operas, but today’s stage directors, and consequently

audiences, often ignore the needs of the dramas upon which his operas

are constructed and focus instead on creating “entertainment” by some

other means than a forthright presentation of the plot acted out

convincingly on stage. Among Verdi’s large output, Il trovatore

has been especially ill-served as a stage drama, and it has come to be

known primarily as a work with a silly plot that is performed mainly for

its glorious music. Failing that, it offers at least an evening of

robust singing.

This January 11, 1941 broadcast recording of Verdi’s Il trovatore

undoubtedly stands above all other recordings of this great opera in

its matching up the character of the voices we hear to the personalities

of the characters in the drama, giving us, for once, a convincing sense

of the drama and allowing us to appreciate this opera more completely

as a music-drama than any other performances we are likely to encounter.

That it is also gloriously performed, musically, by at least three of

the principals, all of whom offer up excellent Verdian style as well as

vocalism, and is also quite well conducted by conductor Ferruccio

Calusio, are almost rendered pleasing byproducts by the convincing

nature of the whole enterprise. This was one great afternoon indeed at

the old Met.

Admittedly, the challenges presented in making the characters of Il trovatore

come to life as living beings are formidable, even taking the opera as

pure melodrama. Consider Manrico, the eponymous troubadour. The opening

scene of Act III reveals that the immolation of the infant boy by

Azucena when attempting to extract revenge on the Count who had burned

her mother at the stake, had occurred a mere fifteen years in the past,

meaning that Manrico is but a lad of sixteen to eighteen, depending on

the age of the two boys at the time of Azucena’s actions, which is not

made entirely clear. Yet somehow, in his few years he has become (1) a

minstrel gifted enough to capture the heart of a fair maiden with his

singing (as Leonora discloses in her opening aria), (2) a warrior

leading his own band of fighters, as part of an insurgent group,

sufficiently belligerent to give real trouble to a reigning count, (3)

an obviously talented jouster on horseback, skilled at knightly games

(as also recalled by Leonora in her opening scena), and (4) a

lover capable of capturing the attentions of a maiden who is obviously a

great lady. And all this, while having been raised by a band of roving

gypsies. (For present purposes, we are ignoring the fact that he is

going to be sung and portrayed by a large-voiced tenor capable of

stentorian delivery, not to mention sustained high C’s.)

Perhaps the most fully developed of the principal characters is the

older gypsy woman Azucena, Manrico’s putative mother, who should be sung

by a large, deep female voice that can suggest great maturity. We do

not learn her age, but she was clearly of child-bearing age shortly

before the immolation of the child fifteen years in the past. She drifts

in and out of reality yet expresses genuine maternal love for Manrico,

whom she has raised as her son and who believes that he is her son. As

so often occurs in Verdi’s operas, the dramatic relationship between a

parent and an adult child is well exploited and developed, adding

dramatic depth to both characters. Manrico must express dismay at his

mother’s unintended revelation that he may not be her natural son, and

his maternal love for her lies at the center of several important

scenes, including his most famous scena where he must abandon

his new bride-to-be to race off and rescue his mother, who has been

captured by the vengeful Count. While Azucena provides a dramatic mezzo

or contralto with outstanding dramatic possibilities, Verdi has also

made her role quite demanding vocally, with the icing on the cake being a

capricious high C written into a cadenza, published in the score

(dramatic mezzos and contraltos suitable for the role can be forgiven

for eschewing it).

The dramatic duties of the Count, who is also Manrico’s romantic

rival, are largely limited to establishing a ruthless character, his one

overwhelming trait being his dark obsession to “possess” Leonora, with

no apparent regard for her happiness or wellbeing. And he is allocated

the final dramatic reaction, as the curtain falls--the realization that

he has just murdered his own long-lost brother. Leonora herself is saved

from being a stock character by a dramatically forceful last act, where

her character springs to dramatic life, as she sacrifices her life to

save that of her beloved.

As indicated above, one will not likely encounter a single

performance elsewhere in which all of these dramatic requirements are as

convincingly met as they are in this one. Il trovatore, as an

operatic drama, is vividly and movingly brought to life by the

coincidence of at least three remarkable and believable

characterizations by the principals.

We begin with the critical fact that both of the members of the

couple at the center of the drama sound convincingly young, in addition

to meeting all the other substantial requirements of their roles, which

is no mean feat. It is safe to say that no 20th century tenor

has fulfilled the almost impossibly diverse requirements of Manrico

quite as fully as Jussi Björling, a Swede who arguably became the

greatest all-around Italian tenor of his time. Apart from possessing a

meltingly beautiful tone, one which can fairly be described as both

Italianate and Nordic at the same time, what sets him apart from almost

every other Manrico on recordings (or encountered in person by this

writer), is the fact that early in his career, he achieved full

confidence in the power of his essentially lyric voice to project

without forcing the tone or trying to sing with a larger tone than he

possessed. Coupled with this vocal confidence was an obviously

intelligent, well schooled mastery of true Verdian musical style. Il trovatore harks back to bel canto ideals of Verdi’s early period, which followed upon the great bel canto

era of Rossini, Donizetti and Bellini, and Björling understood and

delivered the long line and generous legato that is the essence of good bel canto

style. The result was his ability to essay a number of Verdi roles

almost always sung by heavier voices than his, including Manrico. There

was enough bright metal in his tone to portray the warrior, but at the

same time enough lyric beauty to succeed and convince with the lyrical

phrases of the troubadour, the devoted son and the ardent lover, in a

way that larger voiced Manrico’s do not seem to encompass (excepting

perhaps Caruso, of whose Manrico we can hear only a few recorded

samples). We never get the sense that he is oversinging or compromising

the integrity of his voice with such a dramatic role, and further he

offers a level of involvement in all the various aspects of the

character that is very rarely encountered—when we add up all the

successful elements of his portrayal, he actually moves us, in a role

that too often “reads” as pure cardboard.

Fortunately, we have a generally excellent commercial recording of

Björling’s Manrico, the 1952 RCA recording that also features Zinka

Milanov, Fedora Barbieri and Leonard Warren, conducted by Renato

Cellini, and that recording has rightfully been regarded by many as the

“gold standard” among commercial recordings of Il trovatore.

And there are other live recordings of Björling’s Manrico, but as an

overall experience of this opera, they are all surpassed by the present

one.

The little known soprano, Norina (Eleanora) Greco, is our Leonora,

and the quality of her performance here makes one realize what a loss

the Met incurred by letting her go after only two seasons. Born in Italy

in 1915 and transplanted as a young girl to Brooklyn (where her younger

brother would be born—he was to become the Hollywood Spanish dancer

José Greco), she was hired by the Met in the 1940-1941 season due to the

absence of Stella Roman, whom no one would seriously contend today was a

superior singer to Greco, on any level, although she was an established

star. That means Greco was literally only 26 at the time of our 1941

broadcast, but she was in fact already experienced in other companies,

including the touring San Carlo Opera Company, in such roles as

Violetta, Santuzza, Mimi and Aida, receiving fine reviews that one can

find on the internet. Operatic writers have not been as enthusiastic

about Greco as they should have been, but the undeniable evidence is

before us in this stunning broadcast.

One can read unfavorable commentary regarding her Aida broadcast at the Met in her second and last season there, but her rendition of “O patria mia” from her Aida

Met broadcast can be heard on You-Tube, and it is creditably done, if a

little effortful, with a fine high C at the climax. The effort one

hears bears no comparison to the heavy laboring of a great many later

Aida’s who struggle so mightily just to slog through the role. Leonora

is obviously a more congenial role for Greco than Aida, and she meets

all of its requirements with aplomb, including excellent musical style

(surprising in such a young performer), fine and often quite beautiful

vocalism, sophisticated sense of phrasing, excellent flexibility,

dramatic fire that makes her Leonora genuinely exciting, and a young

dramatic soprano voice of great appeal and promise. Her final act is

especially moving, and her interaction with Björling is outstanding. In

short, hers is a most winning and complete performance; she would be an

instant superstar today.

As much as we appreciate and honor the excellence of the Trovatore

Leonora of Zinka Milanov, Björling’s partner in the fine RCA recording,

in what could be argued to be her best recording of a Verdi role, there

is no denying that her voice, despite her often beautiful tones, has a

matronly quality that militates against dramatic believability in this

opera. She is quite obviously bested in this regard by Greco, whose

youthful Leonora is ultimately the more satisfying one. There is a

smaller issue as well, in that Greco’s Italian diction is impeccable,

unlike Milanov’s, which includes some occasional oddities.

This brings us to the superb Azucena of the very underrated Bruna

Castagna. There are a number of fine recorded Azucena’s, but none of

them quite measures up to the level of this one, considering the

totality of all the elements she brings together in this memorable

performance. Her dramatic conception is quite imaginative, in fact

captivating, and her vocalism very beautiful, easily meeting all the

requirements of this difficult role. The only real fault that can be

registered with her singing is her rather habitual tendency to bringing

her chest tones up substantially higher than we normally hear in such

grand, dramatic mezzo voices of her size and caliber, resulting in some

fairly dry tones here and there. One can find live performances where

this tendency can take over and spoil the beauty of her singing, turning

it rather blatty, but here things remain well under control. The

preservation of this broadcast goes a long way toward making up for her

plainly unwarranted absence from commercial opera recordings. She was a

major artist, and if her Leonora and Manrico were not also so

outstanding, she would have stolen the honors in this performance.

The Count di Luna of Francesco Valentino at least offers the right

sort of voice for the role, even if his performance is short on musical

distinction and polish. In short, he is adequate. Bass Nicola Moscona

fills out the smaller part of Ferrando, including that character’s

quirky but effective first act aria, quite well. Overall, we are

unlikely to find Il trovatore better served than we find it here.