This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Cast Listing

- Cover Art

Furtwängler's 1950 Ring Cycle Part 2: Die Walküre

"Furtwängler surpasses himself and almost everyone else in sheer incandescence" - Gramophone

"Pristine has done wonders for Furtwängler's La Scala Ring"

- Alex Ross, The Rest Is Noise, 2013

Now, this is a miracle. I never thought to live to hear this. Yes, I bought back in the day—and still have—the Murray Hill LPs of these performances from circa 1977, which, when played, sounded as if they were coming from a phone left off the hook in La Scala’s lobby. I did recently invest in the Music & Arts Programs Of America CD set, and it was a big improvement over the LPs, but your Rheingold leaps way far ahead of it into a vivid realism that I’d never guessed was hiding in its former iterations. I’m counting the days until Die Walküre and beyond...

G.T., e-mailed response to hearing Furtwängler's Das Rheingold on Pristine PACO089

My major tasks here have included digging out not just some credible bass, but a fullness and richness of tone that comes as close as possible to reality whilst battling high levels of hiss and rumble, and thousands of bumps and thumps that I can only assume emenated from feet on the stage. Meanwhile, and with Rossini's witticism "Wagner has great moments but dull quarter hours" in mind, I came to the conclusion that perceived excitement levels in this performance were in inverse proportion to audience coughs. I've done what I can to reduce their appearance in the slower, quieter sections that some in the Italian audience may have found less than gripping. However, attempting complete eradication of audience noise would cause major musical damage, so some unwanted noises must inevitably remain. Although in places evidence remains of tape disintegration, as in Das Rheingold, but overall I hope and believe we have another "miracle" of "vivid realism" here in Die Walküre!

Andrew Rose

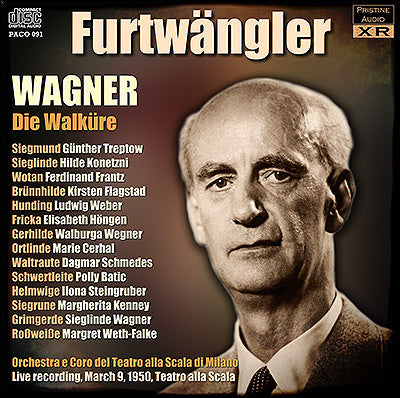

WAGNER - Die Walküre WWV 86B

Siegmund Günther Treptow

Sieglinde Hilde Konetzni

Wotan Ferdinand Frantz

Brünnhilde Kirsten Flagstad

Hunding Ludwig Weber

Fricka Elisabeth Höngen

Gerhilde Walburga Wegner

Ortlinde Marie Cerhal

Waltraute Dagmar Schmedes

Schwertleite Polly Batic

Helmwige Ilona Steingruber

Siegrune Margherita Kenney

Grimgerde Sieglinde Wagner

Roßweiße Margret Weth-Falke

Orchestra e Coro del Teatro alla Scala di Milano

conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler

Live recording, March 9, 1950, Teatro alla Scala

Fanfare Review

This Walküre cannot have been an easy task, yet the result is a hitherto unheard of presence that enables us to wonder anew at this majestic performance

The Scala Ring conducted by Furtwängler is a monumental achievement and fully deserves to be heard at its best. And so it is that once more we sit in debt to Andrew Rose of Pristine Audio. This Walküre cannot have been an easy task, yet the result is a hitherto unheard of presence that enables us to wonder anew at this majestic performance.

Take the very opening. There is a tremendous clarity here that seems to match the fevered intensity Furtwängler sets up so well. Clear also is Furtwängler’s attention to Wagnerian counterpoint (in the minute or so prior to Siegmund’s entrance, for example). Bear in mind on occasion the sound can be quite fragile still, for example track 2, around the three-minute mark, but at no point anywhere in the piece is it overly distracting to the musical flow.

The act I singers are well balanced. Günther Treptow has a heroic edge to his voice (almost Mime-like at times) and is quite fascinating when relating histories. He is capable, too, of moments of restrained, lyrical magic. Towards the end of the act there is a tendency to strain (perhaps even to approach a bark). Hilde Konetzni is impetuous and eminently believable. One might reasonably wish for a Hunding that is more jet black in sound than Ludwig Weber, though. Perhaps the problem is he is not frightening enough. His voice struggles occasionally to surmount the orchestra. It is difficult to imagine him as the primordial hunter/gatherer/thug.

It is Furtwängler’s underlying machinations that ensure the subtleties of the drama remain clear to the listener. The Scala orchestra reacts in chameleon-like fashion to his direction, ensuring a strong arrival on the cries of “Wälse” (given some space here) and then illustrating, like surely no other, the dance of the moonlight in sound; the arrival on “Nothung” is similarly expertly managed, the slightly scrappy brass playing unable to mar the moment in the slightest. The sheer sensuous outpouring of the act’s later stages is due to Furtwängler and his orchestra, though. The web of sound he creates is surely unparalleled, while in no other version is so much orchestral detail so flawlessly evident in the closing measures of the act.

The Wotan, Ferdinand Frantz, seems backwardly placed at his first entrance in the Second Act; Kirsten Flagstad’s glistening Brünnhilde is closer. Yet the dialogue is perfectly managed. There is no space here, or anywhere else in the long central act, for longeurs. Elisabeth Höngen is a Fricka with a spine of steel, her voice pure drama. It is of course Furtwängler who spins the thread that runs through the experience. In his hands, one feels that this central act truly holds the key to Walküre. Frantz delivers all the flawed nobility of his character, a nobility that runs right through this act’s second scene. The true mastery here though is Furtwängler’s: Try the instrumental color alchemy he achieves in the woodwind (end track 13). The act’s vast span is impeccably shaped, culminating in a fourth scene that includes moments of unutterable tenderness, while its final climax is unbearably exciting. To hear this (almost) uncluttered and clear is a minor miracle. Bear in mind there is a change of disc (the latter-day equivalent of turning the LP) towards the end of the Second Act (the third disc begins with scene 5’s “Zauberfest”).

The woodwind trills of Walkürenritt seem positively infernal. There is something of a momentary change of perspective around two minutes in. The Valkyries are a feisty lot, and there is some stand-alone virtuoso string playing. Act III again brings a proper sense of over-arching form from the conductor, enabling dramatic climaxes, loud or quiet (“Hier bin ich, Vater”) to register to their fullest. Frantz comes into his own in this final act, clearly aflame with anger in the earlier stages. Flagstad seems to project all of Brünnhilde’s vulnerability at “Was es so schmählich” (scene 3); yet the dialogue between them is effectively managed by the conductor, who seems to hold the key to the dramatic trajectory. Flagstad’s sense of the lyric is pronounced here, which heightens the poignancy of the situation. As always in this performance, though, it is Furtwängler that creates the sense of the monumental and of inevitability. The sense of momentum towards the famous farewell means that when it comes it is dripping in meaning. Frantz seems to find his finest form at this point; but has there ever been a finer, more gossamer fire than this?

This is certainly not the first incarnation of this splendid performance (LP versions appeared on labels such as Murray Hill, Everest, and Cetra; CD on Fonit Centra, Gerhardt, and Music & Arts), but the sonic improvements make it the only one worthy of serious consideration. With this upholstering, one can properly hear Furtwängler’s intent, his integration of large and small scale. There are blips (CD 1, track 6, around three minutes in), but even to mention them seems churlish. Andrew Rose gives a detailed résumé of problems and solutions on the Pristine website, including the trimming of the coughing of distracted Italians. The studio 1954 recording sits well on Naxos in a transfer by Mark Obert-Thorn (reviewed briefly by Henry Fogel in Fanfare 30:4), while the 1953 RAI deserves shelf space right next to this 1950 Scala.

Colin Clarke

This article originally appeared in Issue 37:1 (Sept/Oct 2013) of Fanfare Magazine.