This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

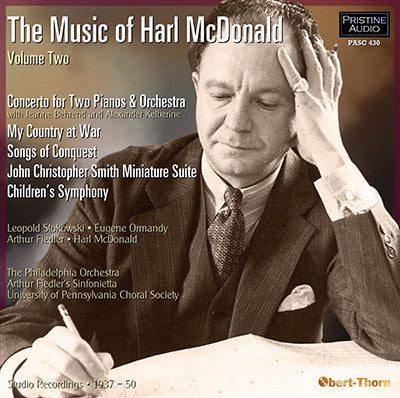

Harl McDonald - Second volume celebrating the music of a forgotten American composer

"I can think of no living American composer who surpasses McDonald at his best. It’s time he was rediscovered" - Fanfare

This second release devoted to the works of Harl McDonald (1899 - 1955) begins with a Concerto for Two Pianos whose eclecticism reflects the wide-ranging influences of the American composer. The second movement variations start with a Bach-like original theme, while the third is inspired by a dance of northern Mexico called the Juarezca.

My Country at War gathers together three of McDonald’s prior works into a suite. The first movement, originally titled Overture 1941, premièred two days before the Pearl Harbor attack that drew America into the war that was already raging in the rest of the world. The second was inspired by the unsuccessful attempt by American forces to withstand a long siege at Bataan. The final two movements were originally set for baritone and orchestra, but revamped without soloist for the suite.

The cycle Songs of Conquest, based on poems by Phelps Putnam, looks back with pride at the achievements of the American pioneers while looking forward with unease at the then-current world situation. The first song celebrates humankind’s triumphs (“Man has prevailed ... over insect and beast/He has forgotten the variable seas”). The second depicts man as alone and terrified (“I am one who am solitary ... I have hurled my questions into the universe/I have pressed them into the earth and into my flesh”). The third makes a statement about nations being able to resolve their differences rationally, a sentiment which must have already seemed like a lost cause by the time this was recorded (“Let us declare ... That the weight of seeing is upon us”). The final song returns to the pioneer theme (“We have cut ourselves from our home as with an axe/The sea could not stop us, being our simple road”) before ending with a reprise of “Man has prevailed”.

The Miniature Suite presents McDonald in the rôle of

arranger. John Christopher Smith was a protégé of Handel, who later

became an amanuensis to his patron when the older composer became

blind. The three movements were drawn from Smith’s My Hand and Musicke Book, published in London in 1784.

Like his suite From Childhood on Volume One (PASC 402), McDonald drew upon nursery rhymes for his Children’s Symphony. Here, he introduces young people to symphonic structure by using familiar tunes in a four-movement framework, each of which has a principal and a secondary theme. The songs used are “London Bridge is Falling Down” and “Baa, Baa, Black Sheep” in the first movement; “Little Bo Peep” and “Oh, Dear, What Can the Matter Be” in the second; “The Farmer in the Dell” and “Jingle Bells” in the third; and “Honey Bee” and “Snow is Falling On My Garden” in the final movement, with a reprise of “London Bridge” to close.

Mark Obert-Thorn

1 1st Mvt.: Molto Moderato

2 2nd Mvt.: Theme and Variations

3 3rd Mvt.: Juarezca – Allegro

Recorded 19 April 1937 in the Academy of Music, Philadelphia

Matrix nos.: CS 07596-1, 07597-1, 07598-1, 07599-1, 07600-1 & 07601-1

First issued on Victor 15410/2 in album M-557

Jeanne Behrend & Alexander Kelberine (Pianos)

The Philadelphia Orchestra ∙ Leopold Stokowski

My Country at War – Symphonic Suite (1941-43)

4 1st Mvt.: 1941

5 2nd Mvt.: Bataan

6 3rd Mvt.: Elegy

7 4th Mvt.: Hymn of the People

Recorded 20 December 1944 in the Academy of Music, Philadelphia

Matrix nos.: XCO 34020-1, 34021-1, 34022-1, 34023-1, 34024-1 & 34025-1

First issued on Columbia 12241-D through 12243-D in album M-592

The Philadelphia Orchestra ∙ Eugene Ormandy

Songs of Conquest (1937; rev 1939) (Text: Phelps Putnam)

8 The breadth and extent of man’s empire

9 A complaint against the bitterness of solitude

10 A declaration for increase of understanding among the peoples of the world

11 The exaltation of man in his migrations and in surmounting of natural barriers

Recorded 20 October 1940

First issued as Victor 18164/5 in album M-823

University of Pennsylvania Choral Society ∙ Harl McDonald

John Christopher Smith (freely transcribed by Harl McDonald): Miniature Suite

12 1st Mvt.: Prelude

13 2nd Mvt.: Air

14 3rd Mvt.: Allemande

Recorded 12 April 1939 in Symphony Hall, Boston

First issued on Victor 4443/4 in album M-609

Arthur Fiedler’s Sinfonietta ∙ Arthur Fiedler

Children’s Symphony (On Familiar Tunes)

15 1st Mvt.: Allegro moderato

16 2nd Mvt.: Andante patetico

17 3rd Mvt.: Allegro scherzando

18 4th Mvt.: Allegro marziale

Recorded 19 March 1950 in the Academy of Music, Philadelphia

First issued on Columbia ML-2141 (LP)

The Philadelphia Orchestra · Harl McDonald

Fanfare Review

I can think of no living American composer who surpasses McDonald at his best.

This is Pristine’s second CD devoted to the music of Harl McDonald.

The first was an absolute triumph, and this one is nearly as good.

McDonald grew up in the American West during the early years of the last

century, and his musical personality exhibits the warmth and

openheartedness one associates with such an upbringing. That is not to

say McDonald lacked technique; he possessed all the compositional

apparatus one expects from a student at the Leipzig Conservatory. In

particular, he was an exceptionally resourceful orchestrator, and gets a

sound that seems as natural to him as breathing. Although he spent most

of his career at the University of Pennsylvania, McDonald was no mere

academic composer. He absorbed influences from many cultures and

different strata of music, from the arcane to the popular. His

compositions are affecting without ever being sentimental. I listen to

McDonald’s music the way I listen to Alexander Glazunov’s symphonies,

relishing his ease of expression, his good nature, and a mastery of form

that picks you up in one place and drops you off comfortably in

another. As with Glazunov’s symphonies, McDonald’s tunes are not

especially memorable in themselves, yet they are of a piece with the

artfulness of his total concept. McDonald is a composer who convinces

you that you are better off for having known him and his oeuvre.

In

the opening movement of the concerto for two pianos and orchestra,

soloists Jeanne Behrend and Alexander Kelberine play with rhythmic

urgency, while Stokowski and the Philadelphians send waves of color

drifting over them. The next movement, a theme and variations, has a

deftness in orchestration underlying pianistic elegance that recalls

Saint-Saëns’s piano concertos. The work concludes with a dance of

northern Mexico called a juarezca, a real toe-tapper which subsides only

for a pianistic interlude that is pure Latin sensual reflectiveness.

Recording two pianos with orchestra is difficult with the best

equipment, so to do it ably in 1937 is a tribute to this recording’s

original producer, who I would guess was Charles O’Connell.

McDonald’s

suite My Country at War seems to me as successful as a more celebrated

work of the Second World War, George Antheil’s Symphony No. 4, “1942.”

The opening movement, “1941,” is a song of foreboding over the events

prior to Pearl Harbor. In the next movement, Ormandy draws haunting

playing from the Philadelphia first chairs in a beautifully subdued

study of American heroism in the failed defense of Bataan. An “Elegy”

follows, with a reflective cello solo, and the work ends with a “Hymn of

the People,” which is a sturdy confection of marches and chorales

leading to a populist gesture, McDonald’s introduction of “The Battle

Hymn of the Republic.”

Songs of Conquest is a choral work set to

poems by Phelps Putnum (texts are not given). It basically is a

celebration of the pioneer spirit, with a sound recalling William

Billings. The composer draws stirring, even rousing singing from his

university’s choral society. The second song, “A complaint against the

bitterness of solitude,” is a rare moment of angst in McDonald. John

Christopher Smith: Miniature Suite is a selection of works by a protégé

of Handel, “freely transcribed” by McDonald. The piece has at least as

much charm as Hamilton Harty’s arrangements of Handel. Arthur Fiedler’s

Sinfonietta play it with style and panache. The composer conducts the

Philadelphians in an alert and enthusiastic performance of his

Children’s Symphony, a largely pedagogical work. It uses children’s

songs to introduce kids to the orchestra and symphonic form. It has

tender moments and raucous ones, like the noisy treatment of Jingle

Bells. I doubt kids today, in the era of Radio Disney, would be drawn to

the Victorian world of innocent melodies McDonald draws upon. Still, it

is an exuberant composition and worth hearing, though it lacks the

staying power of McDonald’s From Childhood—Suite for Harp and Orchestra,

which appears on volume one of Pristine’s series.

Restoration

engineer Mark Obert-Thorn appears to have done a sane and conscientious

job of transferring the various source materials. It is well to ponder

the role of fashion in taking a composer like Harl McDonald out of the

repertoire. Even the revival in the recording studio of American

Romantic music from the middle of the last century largely has passed

him by. Surely American conductors such as Gerard Schwarz and Leonard

Slatkin would have something valuable to say about his music. In the

meantime, we are fortunate to have Pristine’s reissues of the historic

recordings of McDonald’s work. I am not an expert on contemporary music,

but I can think of no living American composer who surpasses McDonald

at his best. It’s time he was rediscovered.

Dave Saemann

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:5 (May/June 2015) of Fanfare Magazine.