This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

Fritz Reiner's masterful way with Richard Strauss

Celebrating the composer's 150th anniversary year

Fritz Reiner is of course closely associated with the music of Richard Strauss. His first stereo recordings, and the first conducted by RCA for what would become their legendary Living Stereo imprint featured Strauss, and it's from those first sessions that Also Sprach is taken. In fact the programme here was to an extent chosen for me - it mirrors precisely that of my first concert in New York at Carnegie Hall in April 2014, celebrating Strauss's 150th birthday. And how better to become intimately acquainted with the music than by presenting an XR remastering of the maestro at work in sound quality that conveys every fine detail better than ever before?

Andrew Rose

R. STRAUSS Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30

Recorded 8 March 1954, Orchestra Hall, Chicago

A stereo recording

John Weicher violin

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

R. STRAUSS Burleske in D minor, TrV 145

Recorded 4 March 1957, Orchestra Hall, Chicago

A stereo recording

Bryon Janis piano

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

R. STRAUSS Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche, Op.28

Live recording, 19 January 1952, Carnegie Hall, New York

An ambient stereo recording

NBC Symphony Orchestra

Fritz Reiner, conductor

Fanfare Review

Reiner makes such good use of the few extra seconds he takes with the NBC group that I prefer Pristine’s vivid reproduction of it

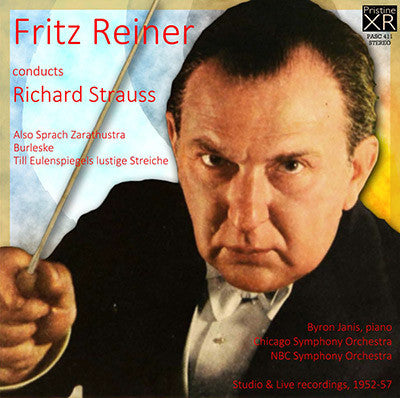

I love the cover on this Pristine release. Imagine yourself as a “fright-palsied oboist” (to borrow a phrase from Oscar Levant) and Fritz Reiner is scowling at you the way he glares out of the cover of this release (“Did I hear a C♯ instead of a C♮?”). Is the ax about to fall? Fortunately for them, the oboists on this recording were spared “the look” (at least I hope so). In June of 1950, Decca recorded Also sprach Zarathustra with Clemens Krauss leading the Vienna Philharmonic. The sound was close to the then-current “state-of-the-art” and it still holds up reasonably well in Decca’s recent reissue of Krauss’s Strauss recordings with the Vienna Philharmonic, including even Salome. As a performance, it need not yield to anyone’s, including even this splendid Reiner/CSO made nearly four years later, in March 1954. The biggest advantage Reiner’s has is the magnificent two-channel sound, even though some listeners may be put off by its not sounding like a “real” stereo recording since, at that time, Reiner had his violins divided with the cellos at stage right. The earliest Reiner/Chicago recordings were made that way. For the following season Reiner, convinced that the two violin sections would hear each other better, switched the second violins over to his left and put the cellos to his right, outside the violas, the same seating that Eugene Ormandy used in Philadelphia. Reiner’s early Don Juan was made the same way, and I suspect that that was the main reason that RCA had Reiner record them over again a few years later. What I don’t understand is, having experienced the sonic delights of his Zarathustra, Dance of the Seven Veils, and Ein Heldenleben, why did RCA then record some Mozart pieces monaurally? Reiner’s Beethoven Third was apparently recorded stereophonically but was never issued in that format in the United States. Why? Reiner’s way with Also sprach Zarathustra is, perhaps inevitably, more hard-edged than that of Krauss, but it and the splendid sound (well preserved by Pristine) certainly put the complicated tone poem across.

Although the Burleske was eventually issued stereophonically, I had heard only the original mono issue until I received this welcome Pristine release. I think just about every performance of this early piece that I’ve heard treats it as an over-ripe specimen of late Romanticism. Perhaps that was the intention of Janis and Reiner, but their approach tends to emphasize the piece’s eccentric rhythms and mood-swings, bringing out a heavy-handed wit that, who knows, may have been Strauss’s intention. Janis’s aggressive pianism runs the gamut from brittle brilliance to melting delicacy and the orchestra contributes the expected precision. In any event, it may not be for all tastes but it works.

According to his biographer, Philip Hart, Reiner conducted Till Eulenspiegel at least 35 times with 15 different orchestras, which may even be a modest estimate. Judging by the four Reiner recordings I’ve heard, I’d say that there was probably little difference among them, but my narrow preference is for the two live ones which, though only marginally slower, seem just a little warmer and, perhaps, even a bit more relaxed. One of them was issued by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra years ago and is no longer available, all the more reason why I take pleasure in touting this similar NBC Symphony broadcast from 1952, which has quite vivid mono sound (or “ambient stereo,” as Pristine calls it) and terrific playing. If real stereo is an important consideration, there’s a rich-sounding Reiner/Vienna Philharmonic Till coupled with Tod und Verklärung. In their efficient way they are both splendid performances, but I think Reiner makes such good use of the few extra seconds he takes with the NBC group that I prefer Pristine’s vivid reproduction of it. Odd that he never recorded the two Strauss tone poems with his own orchestra when he did just about everything of any note except Aus Italien, Macbeth, Metamorphosen, and the Alpine Symphony.

James Miller

This article originally appeared in Issue 38:2 (Nov/Dec 2014) of Fanfare Magazine.