This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Review

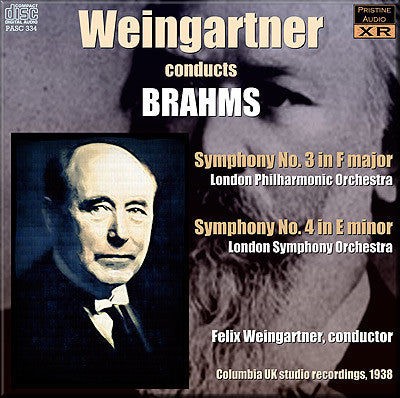

Weingartner's 1938 London recordings of Brahms' Third and Fourth Symphonies

Superb clarity and definition in these new XR-remastered transfers

After sampling a number of possible sources and making a variety of test transfers of these symphonies over a year ago I decided to admit defeat - temporarily at least. There is something about a number of symphonic recordings made in the late 1930s at Abbey Road's Studio 1 which make them particularly tricky to work on. The sound is often congested, there's a lot of what I term "rubbish" between the actual musical content that has been intermittently captured in the upper treble, and they can take a lot of unravelling. No source seems ideal in this respect, but after putting the project to one side I returned to it, both with my original options still open, and also with some 1960s Columbia LP transfers I'd previously dismissed when tackling Weingartner's recordings of the first two Brahms symphonies (PASC281).

This time around the LPs proved far more successful, and I was able to lift from their dimness some fine orchestral tone and detail. Sonically the Third Symphony has perhaps the edge, with slightly more of real value to be found in those vital upper reaches, and less crackle to content with. It also seems to be better recorded in the louder sections - where the Fourth too often seems about to coagulate into a rather heavy mush the Third retains clarity and good instrumental separation.

Andrew Rose

-

BRAHMS Symphony No. 3 in F major, Op. 90

Recorded 6 October 1938

Issued as Columbia LX.748-51

Matrix numbers CAX.8335-42

London Philharmonic Orchestra

Felix Weingartner conductor

-

BRAHMS Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Op. 98

Recorded 14 February 1938

Issued as Columbia LX.705-09

Matrix numbers CAX.8174-83

London Symphony Orchestra

Felix Weingartner conductor

Recording producer: Lawrance Collingwood

Recorded at Abbey Road Studio 1, London

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, April 2012

Cover artwork based on photographs of Weingartner and Brahms

Total duration: 67:28

Review (Symphony No. 3)

The first impression the recording gives is of sweetness and light; the weight is on the slight side, which suits the nature of the streaming music, and the pronounced all-through, unsentimental treatment by the conductor. It may be that the gentle glow in such places as the end of side 1 is thereby a little thinned on the other hand, the lightening helps to carry the music along, and to resolve some of the tonal problems; values can easily be muddied. I like the recording, therefore, because of this element, and also for the way in which the wood-wind falls into place and play, it really sounds like play, not work. The unity that the recording conveys is, too, enhanced by the strings' force being so nearly of the kind that transports one to the concert-room, not the foundry. Firmness and the bread-and-butter qualities of attack are always fine qualities under Weingartner's hand (he has, of course, written on this work in The Symphony since Beethoven). "Brahms's Eroica," said Richter. One does not minutely compare the two; simply, here is the high heart and high humanity which (without accepting all Carlyle's thoughts about the Hero) he seems to have well defined as "the divine relation which unites a great man to other men." The hero is not a superman, nor a man apart; always, he is the essence of the best of ourselves. In the expression of that, Weingartner's spirit, and the recording, seem united.

Second movement (sides 3 and 4). It swells and waves with earnest but not dark power. We may care to note the lift that the figure E, G, upper E gives to it (cf. the " motto" of the first movement, those three ascending-arpeggio notes—there, F, A flat, F—the A flat giving an additional lift. The steady motion rules out some of the emotional stresses that some may prefer, in other readings. You will mark, though, the broadening and quietening, towards the end, which comes all the more warmingly because the rest has been a little lacking in emphasis possibly, even slightly prosaic. Of this mellowing coda no other composer, to my mind, was so sure a master as Brahms. Others exhilarate, pulse with new life, even amaze: does anyone quite reconcile like Brahms ?

Third movement, side 5 and half of 6. It would not, I think, be easy to find a better recorded account of the rich scoring of this - not that the richness floods over you, but that the never very easily-reproduced wind choir blends so well with the strings, and the whole maintains a feeling so elevated yet not aloof. There is a world of interest in the scoring alone, and the instrumental timbre and life are beautifully made moving in this recording.

Deepest pleasure of all is the Finale it begins in the middle of side 6. The flexibility of the handling is apparent at once. Cf. the dark theme, half an inch from the end, with the one, of similar motion, in the second subject of the Andante. The drama: I wonder if it might a little lack power? Yet, though the tone is never aggressive, every note tells. You can hear the parts, even in the occasional dangerously scored sections. Is it tragedy ? The end points a philosophy. Without reading too much into non-programmatic music, one may modestly find, perhaps, some comfort in the end of the work: maybe even hope for some such assurance, after the evil upthrusts of to-day, of—what ? Each to his own heart's hope. I can only testify to the good that I think these records have wrought upon me, this overcast November day in the murky year 1938; and so commend them and their comfort to all who may be inclined to feel and think likewise.

The Gramophone, December 1938

Fanfare Review

Weingartner may be the definitive Brahms interpreter. A mandatory acquisition.

This is the second half of Felix Weingartner’s London Brahms symphony cycle. The First and Second symphonies were reviewed in Fanfare 35: 1. Those performances date from 1939 and 1940, respectively, and were also split between the London Symphony Orchestra and the London Philharmonic. Pristine’s Andrew Rose did the remastering from U.K. Columbia 78s, and reviewing that disc in 35:1, I was so bowled over by Rose’s restorations and by Weingartner’s electrifying readings that when I saw this companion CD advertised, I had to have it.

Weingartner made these in-studio recordings of the Brahms symphonies in almost reverse order. He began with No. 4 on February 14, 1938, and followed it with No. 3 on October 6, 1938. Nos. 1 and 2, in that order, came a year apart, in February 1939 and February 1940, completing the project before the German bombing blitz on London began in September of that year.

Like the First and Second symphonies, the Third and Fourth are also taken from U.K. Columbia 78s, and even though they’re of slightly earlier vintage, whatever Rose has done to achieve such astonishingly vivid sound is nothing short of miraculous.

Everything I said in my review of Weingartner’s Brahms First and Second could be repeated here. His tempo for the first movement of the Third Symphony is a good deal faster than we tend to hear it in modern performances. But the kinetic energy and dramatic drive Weingartner generates leads to massively powerful climaxes. It’s only part of the story, however, to single out the first movement. Tempos across the board tend to be swift and informed by some sort of primordial, premonitory force. Listen, for example, to the last movement. Weingartner finds a demonic fury in this music I’ve heard no other conductor match.

With this kind of dark and violent message in the Third Symphony, where does Weingartner go in the Fourth? Curiously, not where you might think, at least not at first. His tempo for the opening movement is quite moderate, no faster really than what we hear in most modern performances, and while the music isn’t exactly what I’d call playful, Weingartner keeps it mostly light and transparent, emphasizing the lyrical elements of the score and interpreting Brahms’s non troppo marking to apply not just to the Allegro tempo but to the general character of the movement.

Even the funeral, Phrygian-based second movement avoids a leaden tread and mournful mien. The first entry of the bowed strings at bar 30, for example, immerses you in a flood of caressing, sensuous warmth. Devastation and desolation are saved for the last movement, that shattering chaconne/passacaglia, which gains enormously in its implacable malevolent determination as a result of the previous movements downplaying the hint of catastrophe to come.

Once again, Andrew Rose should be credited for having accomplished nothing short of a miracle in remastering these recordings. There are truly moments when you forget you’re listening to anything other than a brand-new, modern recording. But beyond Rose’s contribution, if you care at all about Brahms, these recordings are obligatory for your collection. Felix Weingartner is one of the closest and most important direct links to the composer who lived long enough into the age of recording technology to have recorded Brahms’s symphonies at a time when 78s had reached state-of-the-art conditions. It’s not a word I often use, but Weingartner may be the definitive Brahms interpreter. A mandatory acquisition.

Jerry Dubins

This article originally appeared in Issue 36:2 (Nov/Dec 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.