This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

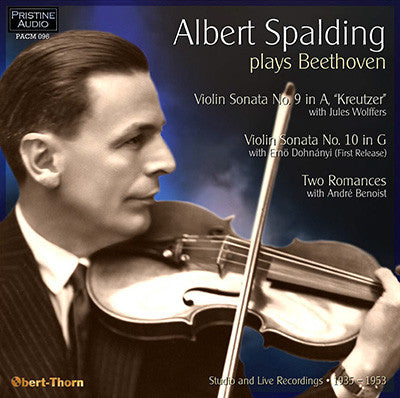

Albert Spalding - the "violinist's violinist" - in rare and unreleased Beethoven

"They call him America’s greatest native-born violinist - Albert Spalding’s tone was as richly expressive as any"

- Gramophone, 2011

After his 1950 retirement from concertizing, Spalding made several LPs for the Remington label, including recordings with Ernö Dohnányi of the three Brahms Violin Sonatas (Pristine PACM 078) and Dohnányi’s own sonata (PASC 381). Following his death, selections from some of his recorded recitals at Boston University were issued on the Allegro and Halo labels. These discs are even scarcer than his Remingtons, with the Allegro LP of the “Kreutzer” (reissued here for the first time) being particularly rare.

The Beethoven Op. 96 sonata, which sees its first release here, comes from a joint recital given with Dohnányi at Florida State University just four months before the violinist’s death. While one might wish that both of the sonatas had been recorded when the violinist was more in his prime, it is valuable to hear, however imperfectly, the conceptions of a legendary artist who was truly a “violinist’s violinist”.

Mark Obert-Thorn

Recorded 11 March & *22 April 1935 in RCA Studio No. 2, New York City

Matrix nos.: BS 89307-3* & 89308-1

First issued on Victor 1788

BEETHOVEN Romance in F major, Op. 50

Recorded 11 March 1935 in RCA Studio No. 2, New York City

Matrix nos.: CS 89309-1 & 89310-1

First issued on Victor 14579

André Benoist, piano

BEETHOVEN Violin Sonata No. 9 in A major, Op 47, “Kreutzer”

Recorded 26 May 1952 at Boston University

First issued on Allegro 1675

Jules Wolffers, piano

BEETHOVEN Violin Sonata No. 10 in G major, Op. 96

Recorded 16 January 1953 at Florida State University, Tallahassee

Previously unissued

Ernö Dohnányi, piano

Albert Spalding, violin

Fanfare Review

Obert-Thorn has captured the raw power of Spalding’s tone production

The aristocratic American-born, though not American-trained, Albert Spalding (of the Spalding sporting-goods family) became the idol for many American violinists in the first third of the 20th century. In addition to his career as a violinist and composer, he wrote interesting and literate memoirs (Rise to Follow) and a biographical novel about the picaresque adventures of Giuseppe Tartini (A Fiddle, a Sword, and a Lady). As Mark Obert-Thorn’s notes point out, he recorded for Brunswick, Victor, and, later in life, Remington. Allegro issued some of his live performances on LP, two of which Pristine has remastered for its tribute to his readings of Beethoven’s violin music (Remington also released his late reading of the Master’s violin concerto).

Spalding recorded Beethoven’s two romances with pianist André Benoist (one of Jascha Heifetz’s early accompanists, though by this time Heifetz had begun working with Emanuel Bay) in 1935; and, like other reissues of recordings from his years with Victor (including a benchmark one of Ludwig Spohr’s Gesangszene), they showcase a more robust violin playing, even though he had reached the age of 46, than do the very late Remington recordings. Obert-Thorn has captured the raw power of Spalding’s tone production, which Victor’s engineers caught close-up. Both romances reveal characteristics which listeners once identified has his personal calling cards—the strong but somewhat raw-boned bowing, but also a pure though somewhat edgy tone, and a straightforward vigor and magisterial authority. He employs portamentos that many will brand as old fashioned; but even purists shouldn’t find these distracting, especially since they never cross the line into exaggeration; and, in any case, they spring from an expressive soil that’s generally more modern than Romantic. In general, his passagework sounded easy and fluent; and the force of his personality makes it clear why his listeners found so much to admire in his playing. Benoist proves a strong-minded accompanist, but he remains in the background.

Spalding and pianist Jules Wolffers gave their live reading of the “Kreutzer” Sonata on May 26, 1952 at Boston University; unfortunately, at 63, Spalding had lost some of the bow control that had characterized his earlier recordings. It sounds as though he had difficulty balancing the bow on both strings in double-stops and as though he occasionally failed to keep noise from disfiguring the tone he once produced so confidently. The first movement sounds fiery if a bit insecure technically. The second is heavy-handed in moments to which he would probably have brought a lighter elegance in earlier years (I’ve noted that older violinists often produce a progressively more glutinous tone as they age); the repeated-note variation, which I’ve heard even students make sound intriguingly springy, plods almost leadenly. The rapid passagework in the finale still crackles in Spalding’s reading, although the double-stops now pose significant difficulties for him. The engineers at the recital came close, capturing lots of extraneous sound; and, at times, it’s not completely clear whether what sounds like faulty tone production might not be instead an artifact of the recording process. On the other hand, the performance itself offers enough glimpses of the earlier Spalding to make it worthwhile hearing.

Spalding’s live reading of Beethoven’s 10th Sonata with pianist Ernő Dohnányi on January 16, 1953 at Florida State University during the last months of his life achieves a more even balance between the violin and the piano. The microphones seem farther away from both instruments, and though occasionally the sound booms, in general the impurities that the recording process introduced into his tone a year earlier seem rarer. And, both Dohnányi and Spalding take a more nuanced approach than the violinist seemed to do with Wolffers. Perhaps Dohnányi inspired Spalding, for the performance seems more invigorated as well as subtler. The nuances turn out to be dynamic as well as rhythmic. Spalding, of course, still displays the general state of technical deterioration that can be heard in his reading of the “Kreutzer” Sonata, but the combination of the collaboration and the engineering help tame its unruly tendencies. The opening of the second movement can be sheer magic, and it comes close here, especially at the end of the piano’s initial statement of the theme. The Duo makes a thrilling sudden shift of tempo in the scherzo, one of many especially felicitous touches in an overall felicitous performance. Several technical slips in the finale, not adding up to much, don’t figure in the evaluative equation. Finally, Dohnányi and Spalding sound boffo in the last big climax before the sonata’s end. The two also recorded all three of Johannes Brahms’s violin sonatas for Remington.

Did Spalding belong in the same category as Heifetz or Spalding’s near-contemporary, Joseph Szigeti? Perhaps technically not the equal of Heifetz and interpretively not so penetrating as Szigeti, he nevertheless spoke with a voice of great authority, identifiable in almost every measure. How does he compare to violinists of the early 21st century? I’d hazard a guess, a partially baked idea, that if he couldn’t compete technically, he rose above many of the young violinists who have only recently completed their long conservatory training in possessing the authority imparted by a strong personal voice. That’s why this recording should appeal to those who love the violin literature as much today as his recordings did several generations ago. Strongly recommended generally, and urgently to violinists. Robert Maxham