This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Reviews

"Heifetz is really in a class of his own" - Gramophone

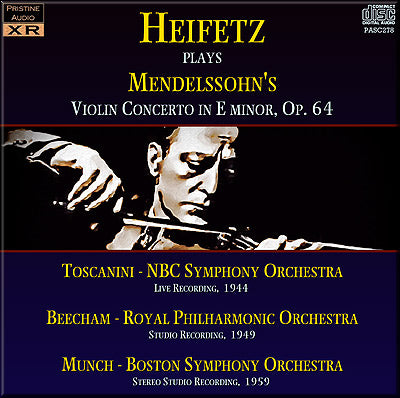

Two studio and one live - three contrasting, superb performances, XR remastered

This release allows the listener to hear not only the great Heifetz at his virtuoso best, but also to compare and contrast the three complete recordings of Mendelssohn's concerto which are listed in Beecham's main discography (which predates Pristine's issue of the Cantelli recording of 1954,. PASC094). In terms of pacing there's little between the 1944 and 1959 recordings - the Toscanini is marginally faster than the Munch - but it is in the Beecham second movement, as highlighted in the Gramophone review above, where the music is given the greatest room to breathe, a full 23s longer than the relatively swift Munch recording.

Each recording was XR remastered using the same modern reference recording, yet each retains its own distinct sound and style - and obviously sound quality improves with time, though each has shown considerable improvement over the original source recordings.

Andrew Rose

-

MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64

Recording No. 1 (mono/Ambient Stereo):

NBC Symphony Orchestra

conductor Arturo Toscanini

recorded 9th April, 1944

Recording No. 2 (mono/Ambient Stereo):

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

conductor Sir Thomas Beecham

recorded 10th June, 1949

Recording No. 3 (Stereo):

Boston Symphony Orchestra

conductor Charles Munch

recorded 23rd February, 1959

Jascha Heifetz, violin

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, March 2011

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Jascha Heifetz

Total duration: 73:01

"There's no doubt about it, Heifetz is really in a class of his own; it's an insult to him to make comparisons, as though he were just another fine violinist. One feels exactly the same as with Horowitz: once you put the needle down, you're confronted. There's great fire and passion in the playing, and a lovely relaxed lyricism in the gentler passages, which is carried over into the Andante (as pure and sweet and unsentimental as anyone could wish) and into the pensive introduction of the finale. The finale itself is of course taken at top speed, and provides a feast of breathtaking virtuosity."

from The Gramophone, March 1960 (review of Munch/BSO recording)

"It is, I think, safe to say that the sweetness and calm of the slow movement theme has won as many adherents for the work as anything; and, as some people may try out this set at the dealer's by sampling this movement, it should be said that Heifetz is here at his best, producing a beautifully shaped line of simple and at the same time warm quality, hut never allowing it to become cloying. Knowing how other soloists have found this movement a pitfall, I count this a very definite point in favour of this recording."

from The Gramophone, November 1949 (review of Beecham/RPO recording)

"...the incandescent Heifetz-Toscanini Mendelssohn Violin Concerto of 1944..."

from Gramophone, December 1998 (roundup of historic reissues)

Fanfare Review

Irresistible. Strongly recommended

Jascha Heifetz recorded Felix Mendelssohn’s concerto twice in the studio: on June 10, 1949, with Thomas Beecham and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and on February 23 and 25, 1959, with Charles Munch and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. In addition, two live performances have circulated (also, coincidentally, 10 years apart): from April 9, 1944, with Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra, and from March 14, 1954, with Guido Cantelli and the New York Philharmonic. Pristine brings together the two studio readings with the live recording made with Toscanini; the performance with Cantelli appeared on Pristine 094.

The first reading on the program, with Toscanini, sounds vibrant (despite some perhaps unavoidable noise) in Pristine’s rerelease, which conveys Heifetz’s fiery electricity and tonal splendor in the first movement. In the cadenza, it sounds as though the violinist is standing behind the speakers and reveals the snap of Heifetz’s bow and the full range of his tonal nuances when the orchestra reenters after the cadenza (still, the transfer in Guild’s set of Toscanini recordings of Mendelssohn’s works—2358/9—sounds more full-bodied in the tuttis). There’s more noise in the slow movement, a small price to pay, however, for the rich recorded sound that allows pizzicato accompaniments to reverberate. As in the first movement, that recorded sound again allows listeners to hear Heifetz’s brilliance close up.

In the second reading, with Beecham, the engineers seem to have placed Heifetz further away, but overall, everything seems cleaner, although the cleanliness doesn’t reveal Heifetz’s technical and tonal command any more transparently. Those who believe that Heifetz rethought his interpretations very seldom (which may, on the whole, tend to be true) should note his inflections in the cadenza. His relative relaxation in the slow movement and the purity of his intonation in the finale, a tribute to the performance on the one hand, and the recorded sound on the other, also help make this reading well worth hearing.

The engineers in the third reading, with Munch, seem also to have placed Heifetz further back; approaching the end of his 50s, Heifetz still plays with considerable drive in the first movement, but the difference of 23 seconds that the booklet notes mention in the slow movement between this performance and that with Beecham may strike many listeners less forcefully than the difference whatever polish (over-polishing?) his reading had accumulated over the years may have imparted. Those who consider such things (as we all, on occasion, do) will like to note the timings of the three recordings (Toscanini: 10:50, 7:17, and 6:13; Beecham: 11:05, 7:27; and 6:05; and Munch: 11:03, 7:04, and 5: 57), which may reveal a great similarity but also show how abstract resemblance can mask many differences in energy.

Those seeking Heifetz’s readings of this concerto in thoughtfully restored recorded sound will find Pristine’s release irresistible. Strongly recommended to more general listeners as well.

Robert Maxham

This article originally appeared in Issue 35:1 (Sept/Oct 2011) of Fanfare Magazine.