This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

Fanfare Review

Most strongly recommended.

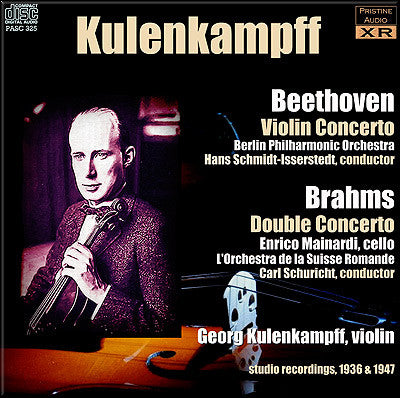

Andrew Rose’s inset notes relate his challenges in remastering Georg Kulenkampff’s 1936 recording of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Violin Concerto: The original recordings, as noted in the Gramophone review he cites from 1954, reached A = 456.57, and he has brought the pitch down to 440. In addition, he had to work around attenuated highs at the ends of the long original Telefunken sides, and accordingly left tape hiss intact in order to preserve Kulenkampff’s tone in the higher registers. He also adjusted the reverberation in Decca’s recording of Johannes Brahms’s Double Concerto from 1947, using the ambiance of Birmingham Symphony Hall in the absence of a “suitably Swiss” one.

Whatever the engineering feats, he didn’t correct the pitch in one of the Beethoven concerto’s early arpeggios, the second note of which seems almost a half-step high. Nevertheless, the first movement makes a strong impression, not least for eschewing devices like portamentos that even some of the later Russians, like Heifetz and Milstein, still included in their expressive arsenal. The first-movement reading, in its general cleanliness and deftness, then, might have been recorded more recently. (Boris Schwarz thought Kulenkampff the most un-German of German violinists.) At about 19:16, a sudden change of timbre intrudes itself, and that may tell the tale of a difficult transition between the original discs. The above-mentioned Gramophone review suggests that Kulenkampff seems labored in the cadenza, but the passagework sounds brilliant nonetheless, with every attack cleanly—even sharply—articulated. On the whole, in fact, Kulenkampff’s general approach, to this concerto in particular and to violin playing in general, reminds me a bit of Leonid Kogan’s (in his 1957 recording with Kiril Kondrashin and the USSR State Symphony Orchestra of the same concerto). The purity of his tone and the chasteness of his trill, more than a simple ornament in his performance of the Larghetto, contribute to a reading generally clean in its style and timbre and serene in its repose (the middle section transcends in profundity the depth that simple relaxation connotes, studded as it is by moments of piercing insight; the Gramophone reviewer simply called it “serenely beautiful”). Kulenkampff may bring more character to the episode than to the rondo theme in the last movement, but the rondo nevertheless develops momentum, due in part to Hans Schmitt-Isserstedt’s and the orchestra’s granite and Kulenkampff’s incisive hammering at that foundation. But Kulenkampff does more than mindlessly hammer, however sharp his pickax, and occasional slight alterations in tempo seem more than usually subtle and expressive.

Whatever disclaimers Rose may make about the adequacy of Telefunken’s recorded sound, Decca’s reproduction of cellist Enrico Mainardi’s tone in his opening solo make it clear how much the decade-and-a-half improved engineers’ technical capabilities; Rose relates that the Brahms concerto represented Kulenkampff’s second-to-last appearance in Decca’s studio. Mainardi sounds almost sweetly relaxed, if not leisurely, in the first movement’s solos; Kulenkampff matches him in Affekt, light years distant from Zino Francescatti’s and Pierre Fournier’s generally edgier reading, which explores vastly different territory. Carl Schuricht and the Suisse Romande Orchestra provide a richly majestic backdrop for Kulenkampff’s and Mainardi’s ruminations. Schuricht and the orchestra provide another meditative backdrop for the soloists’ discursive reflections in the slow movement. Mainardi again establishes a genially relaxed tempo in the finale, with the emphasis on geniality rather than on relaxation. If the recorded sound captures no warts (such as the wrong note in the beginning of Beethoven’s concerto), listeners may feel that the performance itself doesn’t contain so many moments of sheer transport as does that of Beethoven’s concerto. But if it’s movingly consistent, it’s consistently moving as well.

Collectors of all kinds should welcome the unlabored way in which Kulenkampff made substantial statements (consider, by comparison, Anne-Sophie Mutter’s mannered timbral experiments) and celebrate what Pristine has been able to salvage from the recorded sound. Most strongly recommended.

Robert Maxham

Robert Maxham

This article originally appeared in Issue 35:6 (July/Aug 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.