This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Review

Bronislaw Huberman's complete Bach and Mozart Concerto Recordings

Special 25th anniversary* transfers by Mark Obert-Thorn

This release brings together for the first time in a single place all of Huberman’s Bach and Mozart concerto recordings. The sources for the transfers of the commercially-issued discs were American Columbia pressings: a “Royal Blue” shellac set for the Bach A minor concerto; a large label, post-“Viva-Tonal” black shellac album for the Bach E major (except for the first side, which came from a late-1930s “microphone” label copy); and a small label “Master Works” set for the Mozart.

The original recordings were not state-of-the-art for their time. The hall is over-reverberant, obscuring detail; and the sound is inherently fuzzy and occasionally distorted. (The opening of the Bach E major is gritty on every copy I’ve heard, both European and American.) However, the U.S. Columbia pressings are probably the quietest available for these discs.

For the present remastering of an existing transfer of the Mozart D major broadcast, almost all clicks and pops have been eliminated, pitch variances have been corrected, and as much warmth as possible brought to the originally strident recorded sound. While still far from perfect, I believe it to be a significant improvement over how this performance has been heard until now.

Mark Obert-Thorn

* "Twenty-five years ago this month, I was hard at work on my first releases as a professional transfer engineer ... This month we come full-circle, and I begin my silver anniversary as a reissue producer with a new transfer of the first CD of the three I did for Pearl in October, 1988 to be issued: Bronislaw Huberman’s recordings of Bach and Mozart Violin Concertos, now expanded to include his broadcast performance of Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 4 with Bruno Walter conducting."

Excerpt from Pristine Newsletter article, 25 October 2013, by Mark Obert-Thorn

BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, BWV 1041

Recorded 13 June 1934, Mittlerer Konzerthaussaal, Vienna

Matrix nos.: WHAX 20-2, 21-1, 22-2 and 23-1

First issued on Columbia LX 329 and 330

BACH Violin Concerto No. 2 in E major, BWV 1042

Recorded 13 June 1934, Mittlerer Konzerthaussaal, Vienna

Matrix nos.: WHAX 15-5, 16-2, 17-2, 18-2 and 19-4

First issued on Columbia LX 408 through 410

MOZART Violin Concerto No. 3 in G major, K.216

Recorded 13 - 14 June 1934, Mittlerer Konzerthaussaal, Vienna

Matrix nos.: WHAX 24-5, 25-5, 26-3, 27-2, 28-3 and 29-3

First issued on Columbia LX 494 through 496

MOZART Violin Concerto No. 4 in F major, K.218

From the CBS broadcast of 16 December 1945

Carnegie Hall, New York

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra - Issay Dobrowen (Bach, Mozart Concerto No. 3)

Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York - Bruno Walter (Mozart Concerto No. 4)

Bronislaw Huberman - violin

Producer and audio restoration engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

Further XR processing for Tracks 10 – 12: Andrew Rose

Special thanks to Nathan Brown, Frederick J. Maroth and Charles Niss for providing source material

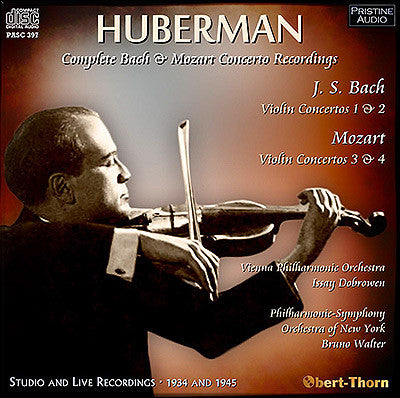

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Bronislaw Huberman

Total duration: 76:12

There is room for much useful discussion about the definition of “classical,” especially as over against “romantic”; but if an example of classical style in the first half of the eighteenth century is wanted, the E major is a splendid one, and it affords excellent opportunity for the exhibition of classical style in fiddling: a fine, nervous sensibility is wanted, with a strong, upstanding, no-finicking clarity. There are easy distinctions to be noticed between the styles of admired players. Huberman, we expect, will not play this work quite like Busch, any more than Szigeti and Menges will give us the same Brahms in the Concerto; but whereas in the modem work there is a world of difference in the degree of romanticism possible in the outlook of various players, in the older work the difference chiefly lies in varieties of bowing and phrasing. Hence we are more likely to agree about the good qualities of any able performance than we are about the interpretation of the Brahms. And an able performance, of course, we are sure to get from Huberman—one that nobody need hesitate to recommend.

W.R.A. - The Gramophone, November 1935

Excerpt from review of Bach Violin Concerto No. 2 in E

Fanfare Review

Huberman deserves be reckoned among great violinists, not only among great humanitarians. Urgently recommended.

Mark Obert-Thorn, who produced Pristine’s release of Bronislaw Huberman’s studio recordings of violin concertos by Bach and Mozart (No. 3) as well as a live performance of Mozart’s Concerto No. 4, notes that the original studio recordings weren’t particularly well made, even for their vintage (the recording sessions took place in June 1934). Henry Roth doesn’t include these performances among Huberman’s best, considering his version of Mozart’s Third Concerto ponderous and Bach’s E-Major Concerto (No. 2) only “marginally better.” But, to begin at the beginning, Huberman and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra bring springiness rather than solemnity to the first movement of Bach’s A-Minor First Concerto, with the ensemble introducing many slight crescendos and decrescendos into the tuttis and the violinist making passagework dance off the string. If Huberman has acquired the reputation for being old-fashioned, this performance doesn’t entirely bear out that impression. In the slow movement, however, he connects notes with portamentos that most modern violinists couldn’t bring themselves to duplicate, yet he keeps Bach’s rhetoric soaring. Neither the soloist nor the orchestra seem inclined to drive the Finale forward, but Huberman nevertheless discharges a strong current of electricity in it, once again combining lightweight articulation with portamentos in an anomalous mixture of old and new.

Huberman sounds highly individual in the first movement of Bach’s E-Major Second Concerto, tonally and conceptually, setting a more recognizable seal on every passage than did violinists such as Jascha Heifetz, Mischa Elman, and Nathan Milstein—or even, later, David Oistrakh. Issay Dobrowen imparts a pronounced character to, and traces the dialogue buried in, the tutti sections. The effect here will perhaps seem as disfiguring to some as it will transcendent to others. No one able to accept the anachronisms (such as the piano continuo’s prominence when the textures thin) even grudgingly should be able to deny the violinist’s (or the conductor’s) penetration, however musical manners may have changed in the last 75 years. Listeners may also react differently to the portamentos that Huberman introduces so lavishly into the slow movement (Roth dismissed them out of hand). And if Huberman never sounds like what Roth described as a “tonalist” (like Heifetz and Elman)—and even if his timbral palette takes some getting used to—the most hostile listeners should be able to hear through it to the music’s core, which Huberman penetrates. The engineers have allowed him to disappear behind an orchestral veil toward the end of the movement. In the Finale, though his passagework sounds abrasive at times, it’s always light and vibrant.

Roth thought Huberman’s recording of Mozart’s Third Concerto to be ponderous, but that can’t be because of heavy-handed bowing or sluggish tempos (in fact, his energy in the first movement recalls Isaac Stern’s); only the cadenza sounds at all perfunctory. If the slow movement doesn’t seem to waft down from violinistic heaven (the accompanying triplets not so downy as angels’ feathers), it still provides a moment of sweet respite (despite its high level of activity) from the surrounding Allegro and Rondo. In the Rondo, he races at a tempo that might have earned a speeding ticket in another time (remember Eugène Ysaÿe’s dash through the Finale of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto), reminding listeners along the way of Mozart’s wit as well as of his elegance.

The recorded sound from the live performance of the composer’s Fourth Concerto 11 years later places Huberman far to the front of the orchestra—this time the New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra conducted by Bruno Walter—allowing listeners to hear all the better the sparkle of his off-the-string bowings. The Concerto’s slow movement provides contrast after such a vivid performance of the Allegro, with Huberman taking advantage of his instrument’s lower registers in its cantabile subsidiary theme; his walk up and down the scale at the movement’s end sounds highly individual. Huberman and Walter endow the Finale with flinty wit. (Ruggiero Ricci once answered a question about the hardest violin concerto of all by citing the Finale of this work, with its tricky bowings—perhaps a surprising answer from one who has tackled finger-twisters that others avoid—or at least, did avoid until he attempted them). Though some of the passages in this performance sound rough-hewn (exhibiting occasional ax-like articulation), they all bubble.

For the second and third Book of Lists, Isaac Stern and Yehudi Menuhin, respectively, compiled rankings of the 10 best violinists, with Stern including Huberman and Menuhin not. It’s clear from the older violinist’s performances of this non-Romantic literature alone, not perhaps his specialty, that Huberman deserves be reckoned among great violinists, not only among great humanitarians. Pace Roth, urgently recommended.

Robert Maxham

This article originally appeared in Issue 37:5 (May/June 2014) of Fanfare Magazine.