This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Historic Review

Bruno Walter's Mahler 5: "First class in every way" (The Gramophone)

A new XR remastering that sounds truly incredible - for any recording of this vintage!

This recording, made at the end of the 78rpm direct-to-disc era, both benefits and suffers as a result, as has been clear from previous issues. The Philips LP referred to in our Gramophone review struggled with a lack of clarity, especially at the top end, whilst later CD issues have suffered a surfeit of surface noise. No previous issue has successfully tackled the somewhat constricted sonics of the original recordings in the manner that this new 32-bit XR remastering has succeeded in doing, unlocking the broad sweep both of Mahler and Walter's collective visions. Rebalancing the orchestral tone has revealed a fuller and more glorious sound than I had dared to anticipate in a remastering process that has taken on numerous incarnations since I began it eight months ago.

Andrew Rose

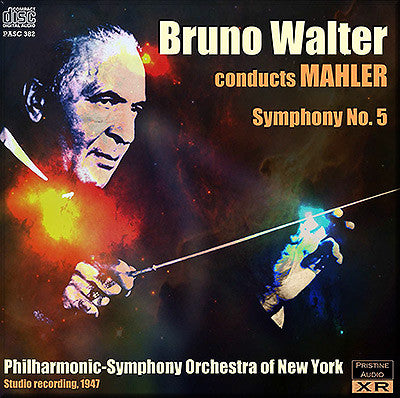

MAHLER Symphony No. 5

Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York

Bruno Walter conductor

Recorded 10 February 1947

Carnegie Hall, New York

First issued as Columbia 78rpm album MM 718

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, July 2012-March 2013

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Bruno Walter

Total duration: 61:29

REVIEW Symphony No. 5, 1957 UK LP issue

In THE GRAMOPHONE for November, 1953, I wrote about this

symphony at some length, expressing in general a degree of doubt as to

its total coherence. The enormous structure, however, could scarcely be

given a better chance of making its multitudinous points than on this

new set of discs, which are first class in every way.

Walter

takes very great care, in particular, over accentuation, over the

shaping of every one of Mahler's phrases. The result is often to propel

the music when it stands most in need of propulsion: not all

performances disclose a rhythmic shape to a cloud of notes as clearly as

this one. Particularly does the Scherzo benefit; and the alert reading

results not merely in a winning effect but also in a practical advantage

- the Adagietto can then be accommodated on the same side, leaving the

whole third side of the set available for the Finale, with obvious

engineering advantages.

Throughout the players respond readily

not only to Walter's forward urge, but also to all the other demands of

the music. The brass are on top of their form, with superbly confident

trumpets and rich-sounding trombones; so are the strings, with dash,

unanimity, and, particularly in the Adagietto, a very full quality of

tone. This movement does to some extent lack a clear reproduction of the

important harp part; but the previous Scherzo always makes clear the at

least equally important solo horn part, here most beautifully played.

The recording is sonorous, even in the severest of Mahler's climaxes,

which it approaches without flinching. The sonority does not, save

exceptionally, exclude clarity; and it establishes beyond a doubt the

superiority of this version of the symphony to the earlier Nixa set.

That was very clearly recorded (again, curiously, except as to that

elusive harp part), but the overall sound was not as warm as that of the

new Philips; nor did Scherchen achieve quite the felicities of

phrasing, or, In places, the forward urge of Walter.

M.M., The Gramophone, December 1957 , excerpt

Fanfare Review

With his transfer of the Fifth Symphony, Rose finally reaps sonic gold

Here we have a brace of remasterings by Andrew Rose of several of Bruno Walter’s legendary Mahler symphony recordings; only the monaural New York Philharmonic versions of the First and Fourth symphonies are not included. The results are mixed, with no clear pattern of superiority or deficiency emerging.

In the case of the First and the Ninth symphonies, I compared this Pristine issue against Sony’s 1994 “Bruno Walter Edition” issue; the recent 24 bit remasterings in the seven-CD set of all of Walter’s Mahler recordings for Columbia (see the Classical Hall of Fame review by Christopher Abbott in 35:6), and Japanese Blu-spec issues (once again kindly lent to me by friend and Fanfare subscriber Bob Alps). In the case of the First, I had two different Blu-spec discs available to me, one pressed on gold rather than aluminum, with the more expensive metallic base advertised as providing more enhanced sound. I found virtually no difference between the two domestic issues on the one hand, and the two Japanese issues on the other. Between those two pairs, the preference is probably more subjective than objective. The Japanese versions are mastered at a higher level, so that they have a more immediate presence; however, that brings with it more background noise (particularly hiss in the high treble frequencies) and a slightly less well defined (albeit more powerful) bass register. The domestic versions have a bit less punch, but have whisper-quiet backgrounds and crisper (if less thunderous) bass. Where the Japanese versions score points are in passages such as the opening of the scherzo of the First, in which the unison lower strings have more oomph and color without sacrificing clarity.

How do the Pristine remasterings stack up against this competition? Given that Rose works from LP copies instead of master tapes, remarkably well, but in the end his issue of the First takes a very honorable third place. His sound palette falls about midway between the domestic and Japanese Sony issues. He manages to create a sense of slightly more body than in the domestic Sony discs, but not as much as in the Japanese ones; but in so doing he loses some of the clarity of the bass lines in the domestic versions without gaining all the compensating power of the Japanese ones. It also simply sounds too artificial at times; the opening of the scherzo is again a key indicator, as the lower strings have an unnatural ambience that makes them sound both more distant and less distinct. Furthermore, there is a slight but audible low-frequency rumble from the LP present in the Pristine remastering that afflicts none of its rivals. Rather than striking a happy medium between two extremes, he gets only part of the strengths of each side, along with part of the weaknesses as well. I for one would prefer either end of the spectrum to the middle. I wish that Rose had devoted his attentions instead to Walter’s monaural 1954 New York Philharmonic recording, which might well have yielded far more promising results.

By contrast, the Pristine transfer of the Ninth is far more competitive, and arguably even the one of choice. Once again, Sony’s domestic and Japanese issues present contrasting polarities of remastering philosophies. In this instance, however, the Japanese effort is a major miscalculation, with overbearing high frequency tape hiss and extremely unpleasant harshness in the upper registers. (Did the folks at Opus Kura temporarily hijack Sony in Japan?) By contrast, the domestic issues in the 1994 Bruno Walter Edition and the 2012 24-bit remastering (again, no real difference between them) present an honest, clear sound portrait with minimal tape hiss, and just a touch of the clinically antiseptic lack of definition that sometimes has been the disadvantage of the digital medium. Happily, Rose here manages to go more or less toe-to-toe with the domestic Sony issues for clarity and presence of sound, while retaining the greater warmth of analog LP issues and beefing up the bass. While the rival versions are more or less of equal worth in the two outer movements, Pristine has a slight but clear advantage in the two middle movements. However, given that the seven-CD Sony set can be had for the same price or less than the two-CD Pristine set, its purchase will commend itself to avid Mahlerians and Walterians rather than to more general collectors.

As for the Second symphony, here Rose went up against three different Sony remasterings: the original 1994 Bruno Walter Edition, a 1999 Japanese Sony DSD version, and a 2009 Japanese Sony Blu-spec edition. The 1994 release was my one serious disappointment in Sony’s BW Edition series; while a significant improvement over the Odyssey CD issue and various preceding LP incarnations, it has a somewhat dry and underpowered bass register that does not faithfully reflect either Walter’s sonic palette or the acoustics of Carnegie Hall. It also still had the feeling of the sound being confined inside a cramped sonic box that needed to be opened up and aired out. The DSD version was the first to overcome that to some extent and do this recording a degree of justice, opening up the entire frequency range in general and beefing up the bass in particular, but still having an intangible but real sense of constriction remaining. That edition is still in print and can be ordered from Japan through HMV Japan and similar outlets.

Thankfully, these limitations are abolished at last by the 2009 Blu-spec version—and how! The results of that remastering are simply mind-boggling in their transformative scope; were it not for some residual background tape hiss, one could easily be fooled into thinking it to be a new SACD digital recording, with the soloists, chorus, and orchestra at last bursting forth in unrestrained splendor, grounded in a positively earth-shaking bass register. Alas, that edition appears to be already out of print, though as I type these lines used copies still can be had from Japan for about $60-$100 through Amazon.

Not surprisingly, this Pristine remastering is not competitive with either the DSD or Blu-spec versions from Japan—but then, it is in print and costs considerably less as well. When compared to the 1994 Bruno Walter Edition, it holds its own. The sound is fuller, the bass register stronger, and the boxiness partially opened up. However, I think that Rose slightly miscalculated here and added one degree too much of resonance throughout the entire frequency range, creating a noticeably artificial effect of a bit too much equalization. Taking the exact same approach, but slightly toned down, would have yielded superior results with no drawbacks. Still, if I did not have the two Japanese issues of this recording in my collection, I would want to have this one as an alternative—or should I say antidote?—to the BW Edition release. Rose does score two additional positive points with his version: He puts the entire performance on one CD (Sony’s failure to do so in any of its releases is positively maddening), and he inserts an extra track partway through the finale, so that one does not have to scroll through a single track lasting over half an hour in order to get to the mighty final climax.

With his transfer of the Fifth Symphony, Rose finally reaps sonic gold. According to booklet notes by producer Dennis D. Rooney in the 1994 Sony Bruno Walter Edition release, the performance was originally recorded at 33 1/3 rpm on 16-inch lacquer masters. It was then dubbed for commercial release first onto 78 rpm acetate discs and later onto a master tape. The latter was, Rooney states, used for all LP and CD issues of the performance prior to the BW Edition, which returned to the lacquer masters. Unfortunately, those had suffered abrasive damage in the intervening years, so that the new issue was afflicted at points with patches of loud scratches. Despite some improvement in the sound (though rather less than touted in those booklet notes), I found the extraneous noise so painful that my preference remained with the 1991 digital remastering in the preceding “Masterworks Portrait” series. It was only with the appearance last year of the aforementioned seven-CD set by Sony that a truly listenable edition of this recording finally appeared, that did some justice to the performance. Even so, that release retains a very dry acoustic, flat and lacking in sheen, with an overly subdued bass register.

Rose has managed to correct and compensate for that to a surprising degree. While no one will mistake this for a high-fidelity recording, the orchestral sound now has far more presence and color, with a greatly strengthened bass register. At a few points—most noticeably, the opening trumpet fanfare of the first movement—the sonic retouching is overly apparent and the added ambience draws undue attention to itself, but such moments are few and readily acceptable for the acoustic wizardry worked throughout the whole. For the first time, I can listen to this performance with real pleasure, rather than a somewhat grudging sense of obligation, and for that I am incalculably in Rose’s debt.

As always with Pristine, the packaging is bare bones, and notes must be downloaded from Pristine’s website. This issue of the Fifth belongs in the collection of every Mahlerite; the Ninth is also well recommended, and the Second is quite respectable, leaving only the First as a relative disappointment. Now, on for Pristine to the Fourth Symphony and Das Lied von der Erde! James A. Altena