This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Full Cast Listing

- Cover Art

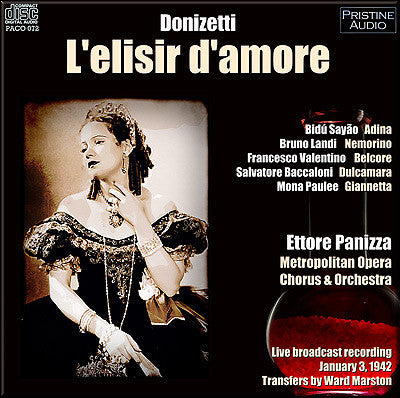

DONIZETTI L'elisir d'amore

Broadcast performance, January 3, 1942, with announcements by Milton Cross

THE CAST

Bidú Sayão Adina

Bruno Landi Nemorino

Francesco Valentino Belcore

Salvatore Baccaloni Dulcamara

Mona Paulee Giannetta

Choir and Orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera, New York

Ettore Panizza conductor

Transfers

by Ward Marston from a set of 5 double-faced 16 inch glass base lacquer

coated discs taken off the air in Providence, Rhode Island.

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Bidú Sayão

Fanfare Review

The Nemorino of this 1942 Met broadcast is Bruno Landi; his is just the kind of voice I want to hear in this role

Unless I am misunderstanding my source, this broadcast of L’elisir d’amore was hurriedly substituted for the scheduled Madama Butterfly (which disappeared until 1946) after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Featuring singers who knew how to sell a song to an audience, the performance unfortunately (but not literally!) suffers “the death of a thousand cuts.” I don’t understand the perceived necessity of making cuts in an opera that has just a little over two hours of music. To be sure, some of what is cut consists of repeated passages, but some of these are fast, tricky ensembles that are Rossinian in their cleverness. It’s still a good show, but cutting them makes Elisir seem blander than it already is. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose department: Here we are in 2012, 70 years later, and the Met is still making almost all the same cuts!

The plot is simple enough: Nemorino, a naïve rustic (one of the dumbest opera characters in history, which is saying something), is in love with Adina, a young woman who owns a farm, but she’s indifferent toward him. She flirts with a conceited Sergeant (Belcore), which fills Nemorino with such desperation that a traveling con man, Dr. Dulcamara, convinces him that he can win her with a magic elixir, which is actually nothing more than a bottle of wine. When the girls in the village find out that Nemorino has inherited his late uncle’s wealth, they start flirting with him. Not knowing about his inheritance yet, he assumes that the elixir is working its magic—even Dr. Dulcamara is convinced. Eventually touched by Nemorino’s devotion (he even joins the army to get money to buy more of the magic elixir), Adina realizes she’s in love with him and they, presumably, live happily ever after. At least we can safely infer who’s going to be the brains of the family.

For the sake of context, I compared this 1942 broadcast with 1967 and 1968 ones (Gianandrea Gavazzeni and Thomas Schippers) and four studio recordings (Richard Bonynge, James Levine, Francesco Molinari-Pradelli, John Pritchard). If I had to live with one of those recordings, it would be Bonynge’s, if only because it’s nearly complete—toward the end of act II, he cuts an ensemble and substitutes an elaborate aria for Adina that Donizetti probably added to appease some demanding prima donna. As is too often the case, the annotator was probably not told of this so there’s no information about the substitution in the booklet, although the libretto does reflect the change. Those who do not find all the cuts objectionable might well prefer the 1967 Gavazzeni, an atmospheric stereo recording that often sounds like it’s a very good in-house pirate job.

The Nemorino of this1942 Met broadcast is Bruno Landi, a tenorino whose soft caress of some of his melodic lines is quite beguiling; his is just the kind of voice I want to hear in this role. How well he was heard in the vast Met I can only guess, but I had no difficulty hearing such smoothies as Leopold Simoneau and Ferruccio Tagliavini there. When he wanders off mike, he virtually disappears during ensembles. Like his fellow male singers, he handles the fioriture decently as long as Donizetti doesn’t throw him any tricky stuff, and he’s at least as good as the formidable competition—Carlo Bergonzi (Gavazzeni and Schippers), Plácido Domingo (Pritchard), Nicolai Gedda (Molinari-Pradelli), and Luciano Pavarotti (Bonynge and Levine). The women, especially technicians like Kathleen Battle (Levine), Roberta Peters (Schippers), and Joan Sutherland (Bonynge), toss most of the elaborate stuff off with such aplomb that I’m surprised when I catch them simplifying some passages. For that matter, Bidu Sayão (Panizza), Ileana Cotrubas (Pritchard), Renata Scotto (Gavazzeni), and Mirella Freni (Molinari Pradelli) all handle the complications reasonably well. I think the most vivid characterization is Scotto’s. The various Belcores sing with the requisite bluster; I particularly like Dominic Cossa (Bonynge) and Giuseppe Taddei (Gavazzeni) but have no complaints about the others—it’s a thankless part in the sense that he’s almost inevitably overshadowed by the other principals, who have meatier roles.

The second scene gets off to a bad start because the offstage trumpet call announcing Dr. Dulcamara’s approach is a half-tone flat; I had thought it was standard operating procedure for offstage instruments to be tuned a bit sharp (the score says the trumpet is supposed to be on stage). Salvatore Baccaloni doesn’t actually sing his part better than the other Dulcamaras I heard—Spiro Malas (Bonynge), Carlo Cava (Gavazzeni), Enzo Dara (Levine), Renato Cappecchi (Molinari-Pradelli), Geraint Evans (Pritchard), and Fernando Corena (Schippers), but he’s a vivid presence and must have been something to savor in person. He was still singing Dulcamara when I began going to the opera, but I only saw him as Geronte (Manon Lescaut), which is hardly a buffo role. One of the things that always seems to be required of buffo basses is that they be able to spit out Italian at a rapid-fire rate, and he could certainly do it, and does it as Dulcamara. With him, as with Fernando Corena, you’re only getting half of his performance when you can’t see him—it was much better, and surely more amusing, to be there. In case you’re wondering, the small role of Gianetta is sung by Mona Paulee. Record buffs may remember her as a recitalist on the old budget Remington label. More nostalgia: Pristine has left a good bit of Milton Cross’s original announcements at the beginning and end of the broadcast. “A blast from the past,” as they say. I like this performance because Sayão, Landi, Valentino, and Baccaloni capture so much of the music’s simple, unpretentious charm, but it’s the most heavily cut Elisir I have ever heard and those cuts drive me nuts.

James Miller

This article originally appeared in Issue 35:6 (July/Aug 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.