This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

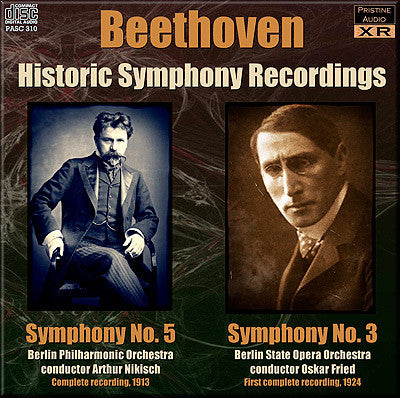

- Cover Art

Two major milestones in the history of recorded music

"These

two recordings offer an important — and in Nikisch’s case, fundamental —

insight into performance and recording practice at the time" - MusicWeb

International

I was tempted to title this release "Historic Gramophone Premières" - after all, it's regularly stated that Arthur Nikisch's 1913 recording of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony was the first complete recording of any symphony to be made. I've heard it introduced as such on BBC Radio Three, and I've read it in erudite biographies. Yet it's not true - it wasn't even the first recording of this symphony. For that we have to turn the clock back a further three years, and dig out a recording made by Friedrich Kark and the Odeon Symphony Orchestra in 1910, issued on the Odeon label. Perhaps it is better suggested that Nikisch's was the first by a "proper", named and highly regarded profesisonal orchestra, under a conductor still rated today as one of the greatest of all time.

Meanwhile Oskar Fried's Eroica was indeed the work's first full recording (though, as often, not all the repeats are there), though in the UK Henry Wood had already recorded an abridged version on six sides some two years earlier, as was his wont at the time - you can find his 1923 Schubert Unfinished Symphony also in a condensed version on Pristine Audio (PASC 041). In that case Wood used four shortish sides, the entire recording running to a mere 12'43". Given a little more space, one might thus usefully explore what exactly constitutes a première recording...

Niggling questions aside, both of these recordings are indeed major historical events in the history of recorded music. Despite the primitive nature of the recording technology used, both offer serious, excellent interpretations by two of the finest exponents of Beethoven of their era. Whilst neither conductor dates back to the era of Beethoven himself, both were firmly grounded in the Romantic musical tradition which began with the composer. Nikisch was regarded by Brahms as having given the finest interpretation possible of his Fourth Symphony, whilst Fried's closeness to Mahler resulted in him giving the second performance of the Ninth Symphony in 1913, together with the first recording of a Mahler Symphony, his Second, also made in 1924 with the Berlin State Opera Orchestra.

To modern ears these acoustic recordings can seem particularly dim and distant, with their orchestras necessarily cut down and their instruments adapted to recordings made tightly gathered around a single horn. Trying to unlock the sound of these performances from their faint, hissy, crackly and, at times, distorted origins, is going to be a tricky business for any remastering engineer. Dynamic range is very limited, even more severely their frequency range.

And yet there is perhaps far more to be heard and appreciated than first meets the ear when hearing the records "raw", and these XR restorations have unearthed a remarkable level of depth and detail. The dynamic range of these recordings has been pushed to the limit, and a far fuller re-equalised sound, bringing out the (albeit limited) bass, allied to a far more rounded lower midrange, helps convey the true sound of the instruments to a degree few will have appreciated or even noticed before, and hopefully opened the drama of these performances up to some who might otherwise havc dismissed them as too archaic to be worthwhile. If this is the case then I would judge this venture to be a success - when given a minute or so to attune my ears it certainly works for me.

Andrew Rose

Recorded 10 November, 1913, Berlin

Transfer from Schallplatte Grammophon 78s

Catalogue Nos 69504-69507

Face Nos 040784-040791

Matrix Nos. 1249-1256

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

Arthur Nikisch conductor

Recorded 1924, Berlin

Transfer from Schallplatte Grammophon 78s

Catalogue Nos 69706-69711

Face Nos B20364 - 20375

Matrix Nos. 1600-1611

Berlin State Opera Orchestra

Oskar Fried conductor

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, September-October 2011

Cover artwork based on photographs of Arthur Nikisch and Oskar Fried

Total duration: 76:21

Fanfare Review

The Fifth triumphantly survives the relatively primitive sonics as one of the greatest examples of malleable, expressive romanticism in action

Arthur Nikisch made a series of recordings before the First World War

with the newly formed LSO, as well as the Berlin Philharmonic. Of them

the most famous and discographically pioneering was the Fifth Symphony

of Beethoven. Actually “pioneering” should be qualified because there

was an earlier traversal of the symphony by the Grosses

Odeon-Streich-Orchester directed by Friedrich Kark made in 1910. Kark

was a kind of German Landon Ronald. I’ve seen this announced on Wing, an

exploratory Japanese label, but have never heard it but it has more

recently been released on the Historic Recordings label (review).

Kark was an important figure in the early history of the gramophone and

it would be good if his other large-scale recordings were represented

more fully for us now.

But let’s return to Nikisch (1855-1922)

whose 1913 recording of the Fifth triumphantly survives the relatively

primitive sonics as one of the greatest examples of malleable,

expressive romanticism in action. Trenchant and powerful, it exhibits

the arch-hypnotist’s art and cogently and, one assumes faithfully,

reflects its conductor’s spirited, rich impulses in the canon. There are

many examples of his flexible approach to tempo relations, and he and

his engineers maintain a good balance between the small body of strings

and the (audible) winds and timpani. The performance has been reissued a

number of times on LP and CD. The Dutton transfer [CDBP9784] is very

smooth; maybe for die-hard 78 fantatics too smooth. Noise reduction has

certainly taken off some treble frequencies but has promoted a

homogeneity of sound that, to many, will be very acceptable. Symposium

[1087-88] sounds radically different again, with a more straightforward,

non interventionist approach. As a result, there is a rather tubby

sound, and it’s a bit muddy and distant. Pristine Audio retains some

surface noise, but has boosted the sound spectrum — these extensions

give a greater sense of density. Where the horns are apt to blare in

other transfers, with this latest release they don’t. It’s a far more

radical piece of surgery, that’s for sure.

The Kark recording was coupled by Historic Recordings with Henry Wood’s very, very abridged 1922 recording of the Eroica.

The disc’s title was ´Beethoven — The Premiere Recordings’. Pristine

has taken the same route, coupling the Fifth with the Third, in their

case Oskar Fried’s 1924 Berlin outing. Their disc title is `Beethoven —

Historic Symphony Recordings’. At least they’re both heading in the

right direction. Unlike Wood’s, Fried’s recording was complete. It’s a

very impressive document, and the first complete recording of the work

on disc. He pipped Frieder Weissmann to the wire by about a year or so.

Single movements had also been recorded by such as Leo Blech and Fritz

Busch.

When he was making the epic acoustic recording of his

Second Symphony, Elgar had the use of 50 players from the Royal Albert

Hall Orchestra. Fried would have had fewer, maybe 30-35. That’s not

inappropriate for what is a most compelling, almost chamber-scaled

reading of great intensity, control and nuance. The distinctive Berlin

Opera winds and their trenchantly contributing brass colleagues ensure

that colour is freely distributed. The string players sound emboldened

to vary and increase the speed of their vibratos in the Funeral March.

Fried ensures that an excellent balance is maintained throughout, that

dynamics are apposite, and that rubato, whilst often pronounced, is

expressively justified. The contours of the performance differ little

from Hans Pfitzner’s 1929 electric recording on Polydor, though there

are innumerable points of difference interpretatively. The Fried

performance has been issued by Music & Arts on CD1185, back in 2006

but I’ve not heard it so can’t comment on their transfer.

These

two recordings offer an important — and in Nikisch’s case, fundamental —

insight into performance and recording practice at the time. Fried’s

recording is much less well known, which makes its reinstatement that

much better.

Jonathan Woolf