This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Cast Listing

- Cover Art

- Contemporary Reviews

Stokowski's trimphant debut - aged 78 - at the New York Metropolitan Opera

Nilsson and Corelli fabulous in this knockout performance of Turandot!

As I was writing the editorial for our newsletter of 6th January,

2012, I was listening through to the work-in-progess version of

Stokowski's 1961 Met Opera Turandot. It was going on quite nicely in the background and, to be honest, my concentration was elsewhere.

Then the famous opening bars of Nessun Dorma

began to play, and Franco Corelli began to sing. It was the first time

I'd heard him sing this aria, and the performance completely overwhelmed

me. My eyes filled with tears and the lump in my throat threatened to

choke me. I had to stop what I was doing and leave the room to gather

myself back together. Clearly the audience were also moved - to such

adulation that Stokowski was forced to stop the orchestra and calm them

down, before going back a line or two and picking up again.

I'm

relieved that this hasn't happened to me before when remastering

recordings for Pristine. It's a terrible handicap! When it came to

working closely on that particular section I had to stop and start a

good number of times, trying my best to tune out of the music and listen

to the noise of clumping feet I was aiming to remove.

It is of

course an aria that I know well - there can be few British males over

the age of 30 who don't associate it equally with the Football World Cup

of 1990, which took place in Italy and meant we heard Pavarotti singing

it before every match on TV. But it's not the memory of yet another

painful moment on the pitch for the England players which causes this

reaction - other performances don't seem to have the same effect. But

the magical combination of singer, conductor, orchestra and occasion in

that Met Opera performance just seems to push the big button marked

"blub" in me, and I don't know why.

How can a few lines of music be so immediately emotionally powerful?

Andrew Rose

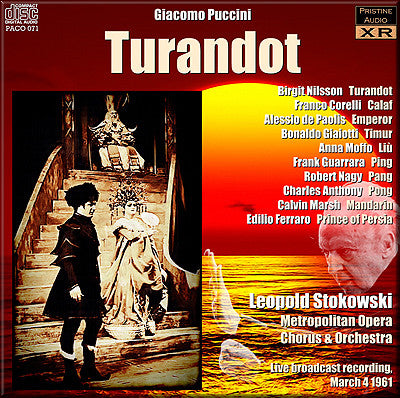

PUCCINI Turandot

Broadcast performance, March 4, 1961, with announcements by Milton Cross

THE CAST

(in order of vocal appearance)

A Mandarin (baritone) - Calvin Marsh

Liù, a young slave girl (soprano) - Anna Moffo

Calaf, the Unknown Prince (tenor) - Franco Corelli

Timur, his aged father, exiled king of Tartary (bass) - Bonaldo Giaiotti

Prince of Persia (non-singing role) - Edilio Ferraro

Ping, the Grand Chancellor (baritone) - Frank Guarrara

Pang, the General Purveyor (tenor) - Robert Nagy

Pong, the Chief Cook (tenor) - Charles Anthony

Emperor Altoum of China (tenor) - Alessio de Paolis

Princess Turandot, his daughter (soprano) - Birgit Nilsson

Choir and Orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera, New York

Production designed by Cecil Beaton

Metropolitan Opera Chorus Master Kurt Adler

Associate Chorus Master Thomas P Martin

Leopold Stokowski conductor

Broadcast performance, 1961

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, January 2012

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Corelli, Nilsson & de Paolis in Turandot at the Metropolitan Opera

Total duration: 1hr 58:41

"For Stokowski (the musical saviour of a situation jeopardized by Dimitri Mitropoulos's death last fall), this was more than the crown of his long musical career in New York - it was the corona. Because of a back injury sustained some weeks ago, he was barely able to reach the conductor's desk on crutches - a slow trek made to a rising clamor of applause and bravos - but, once in place, he was all authority and impulse, dominating the scene with the assurance that comes from complete command.

It should be emphasized that the sonorities Stokowski achieved, whether ear-pounding or gossamer, were always sonorities, not noise, which supported and blended with the strong voices at his command rather than opposing them. There was aural drama in Birgit Nilsson's deployment of her jet-like sound to cope with the inhumane range and power Puccini demands of Turandot.

In Anna Moffo, Liu had an interpreter of equal, if opposite, qualifications to Nilsson's Turandot, a figure of humility and tenderness whose vocal freshness and artistic response to Stokowski's shaping influence provided a touching balance to the Princess of "fire and ice."

How Franco Corelli might perform under a less resolute maestro than Stokowski may be proved soon enough; but this time his prodigious power was all at the service of the score.

The evening was a memorable theatrical experience ... It became a historic one, musically, through the pulsing splendor of vocalism sustained without flaw to the final ringing climax of Act III, when dawn broke on the scene and on Turandot's emotional life."

Saturday Review (11 March 1961) by Irving Kolodin

"When Turandot is as magnificently performed as it was at the Metropolitan Opera House, it is a breathtaking spectacle. The conducting of Leopold Stokowski, who got to the podium on crutches (he is still recovering from a serious accident to his hip), is extraordinarily dashing and vivid, and the cast is of such high quality that few opera houses in the world could touch it. Birgit Nilsson belts out her powerful tones with rare brilliance. Franco Corelli is an ideal Calaf - handsome, virile and vocally splendid. And Anna Moffo is a perfect Liu, touchingly lyric in voice and very beautiful to look at. The lesser characters are played with individuality and spirit, the chorus sings superbly, and all the trimmings are handled with polished artistry. Though Turandot may not be Puccini's greatest opera, its production at the Met is certainly one of the greatest shows to be seen currently on Broadway."

The New Yorker (4 March 1961) by Winthrop Sargeant

"Turandot is Puccini's most fascinating opera and the new production does it justice. Its master is Leopold Stokowski, who made a brilliant Met debut at 78 and on crutches (he is recovering from a broken hip). Having always been a theatrical conductor in the concert hall, he seemed completely at home in the theatre, drawing all the score's turbulence from the orchestra without trying to make it the star of the show at the singer's expense.

Newcomer Franco Corelli, as the prince who stakes his life on winning the cold Turandot, is as handsome as any tenor who ever walked the Met stage and has a big, bronze voice that he can fling forth most of the time without strain. Anna Moffo, as Liu, makes the part far more than the usual sweet rag doll: singing with impeccable beauty of tone but also with surprising force, she gives the character backbone, thus rendering plausible the scene in which she chooses to die rather than to betray Calaf. Beyond a doubt, it is soprano Nilsson who dominates the production. The famed second act aria, In questa reggia, and the whole scene that follows, is one of the most difficult half-hours in all opera. Nilsson's voice was unshakable. She was never shrill and her crystal voice was hard without harshness, cutting without hurting, thus embodying the ultimate paradox of Turandot."

Time (3 March 1961)

"As he slowly made his way on crutches down in the pit, the Metropolitan Opera House exploded into a standing ovation for Leopold Stokowski who was, at 78, finally making his debut as a Met conductor. As Turandot, Birgit Nilsson poured forth such a flood of soaring, stabbing top notes that the ear rang in disbelief. Franco Corelli, the company's handsome new 36-year-old Italian singer, looked like a prince who might sweep a lady off her feet, and he sang like one, too. When asked after the performance how he felt about the tumultuous evening, Stokowski replied: "Really great music, written from the heart. I felt it went to the hearts of those who were listening." Was he unduly tired after such an exacting ordeal? "No," he said softly, "conducting never tires. You give much, but you receive more.""

Newsweek (6 March 1961)

Fanfare Review

If one wants a souvenir of a great night at the opera, this new Pristine release will do quite nicely; it’s also superior to many of the studio recordings

Although she seems to have fought a losing battle over the issue, Rosa Raisa, Puccini’s personal choice to sing the title role at the premiere of Turandot, insisted that neither Puccini nor Toscanini, who conducted the premiere, pronounced the final “t” in the title. Given how the text is laid out, this makes sense to me. After all, one of the advantages of Italian when it comes to singing is all those words that end in vowels. Anyway, I just thought I’d bring this up before I dealt with the recording in question.

I was prepared to be disappointed by this 1961 Met broadcast, which was the next performance after the production’s acclaimed premiere. I had not heard the broadcast but I did attend several of the subsequent performances and found them sloppy and sluggish a good bit of the time. The Met’s original choice to conduct its new production of Turandot was Dimitri Mitropoulos, but his death in 1960 forced general manager Rudolf Bing to cast about for another conductor, preferably a famous one. Fortunately Leopold Stokowski was available and amenable, but several weeks before the first performance, the conductor broke his hip playing with his sons. Determined to meet his commitment, Stokowski made his way to the podium on crutches and, seated, conducted all the performances at the house; with the exception of those in Boston, tour audiences heard the opera conducted by Kurt Adler, the Met’s chorus master. Claiming that none of the orchestration of Turandot was in Puccini’s hand, Stokowski said that he had to hold down the volume as much as he could because the orchestration was too thick when accompanying the singers (but too thin when it wasn’t). He even wrote to Puccini’s publisher, Ricordi, asking for a duplicate of the original autograph score so he could “correct” all the “mistakes” in his. In any event, whatever he may have done, I heard orchestral colors and details that I did not remember hearing before, to the opera’s advantage.

Some choristers and soloists (including Nilsson) later claimed that they had difficulty following him (my impression at the performances I attended), but he and Corelli apparently got along fine and the tenor reputedly considered Stokowski, along with Herbert von Karajan and Antonino Votto, to be one of his three favorite conductors. Calaf was, more or less, Corelli’s signature role, one in which his dashing appearance and ringing high notes really counted for something. Although Stokowski praised Franco Alfano’s completion of the opera, he still makes the “authorized” (by whom?) cut in the duet because “we do not come to the final dénouement soon enough. With the cut we come straight to it, and after that there is wonderful music right to the end of the third act.” He also makes all three standard cuts in the Ping/Pang/Pong scene of act II. Some tempos might have gone a bit faster but there’s enough animation for me and some impressive, majestic moments. I wonder if he actually did make “adjustments.” In his case, there’s ample precedent for it. Some things, to be sure, would have been cleaned up if this had been a studio recording. In the love duet, for example, Corelli and Stokowski are simply not on the same page, and this could be the tenor’s congenital sloppiness—there’s ample precedent for that, too. The passage near the end of act II when Nilsson’s voice cuts through the full chorus and orchestra is impressive here, but in the house it was simply stunning, a truly great operatic thrill. Anna Moffo is an almost ideal Liù. Is it possible to have a voice that might be described as “silvery” and yet “meltingly beautiful”? Soft, floating pianissimos and smooth volume control were part of her vocal arsenal then, too. If only she could have sounded like this for another dozen years! Timur is a passive role and a good one for Bonaldo Giaiotti, the unimaginative possessor of a deep, mellow bass voice. The Ping, Pang, and Pong are ably handled by Frank Guarrera, Robert Nagy, and Charles Anthony; too bad Stokowski didn’t let them do their entire act II scene.

It was inevitable that Nilsson and Corelli would make a studio recording of the opera and they finally did, but even that one was beset by problems. The original choice to conduct the recording, John Barbirolli, refused to work with Corelli. His substitute, Francesco Molinari-Pradelli, was hardly a Corelli favorite and reputedly had disputes with other singers, including Renata Scotto, a last-minute substitute for Mirella Freni, who was ill and unable to sing Liù. Nilsson, who had been appearing at Bayreuth, showed up just as the aggravated Corelli was ready to bug out of the recording sessions early, which he, in fact, did. As a result, the final duet was recorded with Turandot and everyone else in Milan and Calaf, on headphones, in London. Nilsson later complained that “he mastered the dynamics the way he wanted. And that is why you can’t hear my big notes there, because his are way too overpowering.” Ah, singers! Nevertheless, if I had to choose between the two recordings, my choice would be the EMI because I think Nilsson and (especially) Corelli sing a bit better for Molinari-Pradelli (whether they liked him or not) than they did for Stokowski, and Scotto, if she can’t melt like Moffo, is, nevertheless, an outstanding Liù. It’s a tighter performance than Stokowski’s and there is, after all, stereo, less gain-riding, and no audience or stage noise. On the other hand, if one wants a souvenir of a great night at the opera, this new Pristine release will do quite nicely; it’s also superior to many of the studio recordings but not to those of Molinari-Pradelli, Leinsdorf, Mehta, and Serafin.

James Miller

This article originally appeared in Issue 35:6 (July/Aug 2012) of Fanfare Magazine.