This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

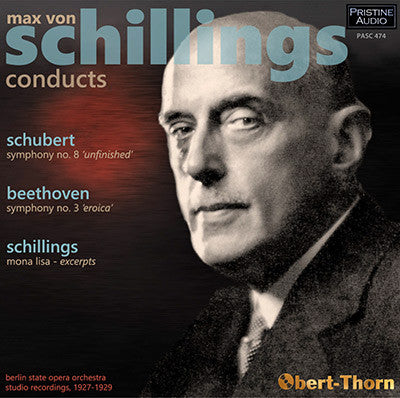

Max von Schillings conducts Beethoven and Schubert symphonies

"Schillings

elicits fine clarity in Beethoven’s contrapuntal filigree ... The

Schillings rendition stands on its own substantial merits" - Audiophile

Audition

Conductor and composer Max von Schillings (1868-1933) has been called a leading figure in late German Romanticism. Born in Düren, he studied at the University of Munich along with Richard Strauss, whose operas he was later to champion. His conducting career began with an appointment as an assistant at the Bayreuth Festival in 1892, where he was named chief choral director in 1902. The following year, he was appointed professor of conducting at the University of Munich, where among his students were Wilhelm Furtwängler and Robert Heger.

Schillings first achieved success as a composer with his monodrama, Das Hexenlied, in 1904. He composed several operas, the most successful of which was Mona Lisa (1915), a La Gioconda-like tale of love and intrigue in Renaissance Florence. It proved to be an international success, being performed at the Metropolitan Opera in New York with Schillings’ wife, soprano Barbara Kemp.

In 1919, Schillings was appointed chief conductor of the Berlin State Opera, where he led the premières of Strauss’ Die Frau ohne Schatten, Pfitzner’s Palestrina and Busoni’s Arlecchino. His removal from that post by the Weimar Republic’s Minister of Culture in 1925 precipitated the anti-Semitic Schillings’ turn toward ultra-right wing positions regarding “foreign” elements and Modernism in German culture. He was courted over the next few years by the rising Nazi party, which appointed him president of the Prussian Academy of Arts in 1932. In that position, he oversaw the removal from their posts of such “decadent” artists as Arnold Schoenberg, Franz Schrecker and Thomas Mann, a purge cut short by his death the following year.

Those willing to consider Schillings the musician

apart from the flawed man will discover an interpreter whose conducting

seems almost modern. Like others of his generation – notably

Weingartner (b.1863), Schalk (b.1863) and Strauss (b.1864) – his

approach favored swift, flowing tempi with a minimum of string

portamenti and willful effects (although he tended to slow down at the

ends of recording sides, as many older musicians did). A 1932 film of

him conducting Rossini’s William Tell Overture, currently on

YouTube, shows an aristocratic figure coolly leading a white-hot

performance. Schillings’ discography is heavy on Wagner; indeed,

between this and the previous Pristine release devoted to him (PASC

228), all but one of his non-Wagner recordings for German Parlophon has

been reissued.

The sources for the transfers were laminated English Parlophones for the Schubert; a German Parlophon for the Mona Lisa

excerpts; and “Viva-Tonal” label American Columbias for the Beethoven.

The last is a particularly problematic recording, made in a small

studio with a shrill midrange, hardly any bass, and an obtrusive hum in

the first movement (which has been removed here). It was set down after

Parlophon had abandoned the Western Electric recording system in favor

of its own proprietary technology in order to avoid paying royalties.

Those willing to listen past its defects will be rewarded with one of

the most propulsive Eroicas of the 78 rpm era.

Mark Obert-Thorn

SCHUBERT Symphony No. 8 in B minor, D.759, "Unfinished"

Recorded 30 November 1927 in Berlin

Matrix nos.: 2-20486/91 (All Take 1)

First issued on Parlophon P-9800/02

SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa, Op. 15 (1915)

Recorded 26 April 1929 in Berlin

Matrix nos.: 2-21383/84 (Both Take 1)

First issued on Parlophon P-9462

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 3 in E flat, Op. 55, "Eroica"

Recorded 24 May, 13 June and 27 June 1929 in Berlin

Matrix nos.: 2-21435/38, 2-21492/95 & 2-21519/22 (All Take 1)

First issued on Parlophon P-9434/39

Berlin State Opera Orchestra

Max von Schillings, conductor

Reviews: Fanfare & Audiophile Audition

Have you ever been so taken with a performance that you enjoyed every minute of it but couldn’t quite find the words to describe it?

My only previous experience with Max von Schillings’s conducting was some of his Wagner performances, which I certainly enjoyed but which left me unprepared for his accomplishment in these two much-recorded symphonies; but back in the late 1920s, when the electrical process was only a few years old, and into the 1930s, there was a lot less competition than nowadays, and it would not surprise me if these were the recordings of choice of the “Unfinished” and the “Eroica” for a decade. Of course, if only for technical reasons, they can’t match the best we have nowadays. They are justly but not rigidly paced, full of relevant detail, and I, at least, get a sense that the music is headed somewhere. Have you ever been so taken with a performance that you enjoyed every minute of it but couldn’t quite find the words to describe it? This month I had a similar reaction to a 1959 “Eroica” by Georg Solti. As for Schillings’s own music, he apparently wrote in the highly chromatic, richly-scored style of the Hollywood composers of the day, ironic because they ended up in California because of anti-Semites like Max von Schillngs who, as head of the Prussian Academy, dismissed such “decadents” as Arnold Schoenberg and Franz Schrecker. He himself might well have ended up churning out movie scores for UFA. He was obviously a good conductor and his death in 1933 deprived him of the honors that the Nazis probably would have heaped on him. If you’re curious, there is a film of him conducting the William Tell Overture that is easily viewable on YouTube.

James Miller

This article originally appeared in Issue 40:3 (Jan/Feb 2017) of Fanfare Magazine.

It has been quipped of composer and conductor Max von Schillings (1868-1933) that “his untimely death saved him from gross infamy, relegating him instead to relative obscurity.” An ardent Nazi, Schillings had begun purging many Jewish musicians from posts associated with the Prussian Academy of Arts. He was featured in the film documentary Great Conductors of the Third Reich. As a teacher of both Frieder Weissmann, Robert Heger, and Wilhelm Furtwaengler, Schillings may have achieved his real immortality. Procucer and recording engineer Mark Obert-Thorn, in collaboration with Andrew Rose and Richard Kaplan, provides us a substantial document of Schillings’ capacities as an interpretative artist.

The Schubert Unfinished Symphony (30 November 1927) exhibits many fine qualities in the course of the reading: the responsive breadth of the musical line stands foremost among a litany of impressive effects. Schillings has a potent sense of musical drama as well, following Schubert’s caesuras to impel the dramatic line toward muscular cadences. The singing line of the main melody proves lyric and virile, nostalgic without cloying. Schillings’ musical culture embraced much in the Romantic tradition that inspired his near contemporary Willem Mengelberg, though Schillings does not attempt a glossy heroism in this performance. Schillings urges the Andante con moto in a solemn but lyrically active tempo, given the often noble tragedy’s being played out. The individual woodwind parts – and French horn – enjoy a resonant, alert shape, along with a finely honed air of mystery. The occasional rubato and portamento effects appear relatively unobtrusively, allowing a palpable breathing space for selected phrase lengths. The performance concludes impressively, a controlled fading into a refined ether.

Schillings’ gothic opera Mona Lisa (1915) explores – as do we all – the secret of the sitter’s smile in the Da Vinci portrait, possibly accountable to the mantra that “sin is the source of all delight.” To a certain extent the opera’s libretto superimposes the Francesca da Rimini tale upon the principals in this opera. The post-Wagnerian Prelude to Mona Lisa (from Parlophone, 26 April 1929) offers a richly orchestrated score, easily compatible with sounds from Richard Strauss or Reger. Arrigo’s Serenade displays the composer’s gift for deft, snappy Italianate lyricism, likely attributable what Richard Strauss accomplished in his own Op. 16 Aus Italien.

After strained, somewhat shrill opening chords, the Beethoven Eroica (from American Columbia, rec. 24 May and 27 June 1929) proceeds in a driven, linear style, much akin to contemporary Felix Weingartner in style. Schillings applies some idiosyncratic touches in terms of pace, slowing down prior to crescendo but allowing his brass to ring prominently as the melodic line surges forward. The bass notes prove hard to discern, though the power of the first music gains a cumulative, impressive momentum.

Schillings makes the Marche funebre the heart of the occasion; and his performance reveals many qualities Liszt would imbibe into his symphonic poems. Again, unfortunately, the bass tones suffer poor acoustics, due, claims Obert-Thorn, to Parlophone’s own technology that eschewed the more felicitous Western Electric process. A light touch informs the middle section, but the haunted march returns with a mournful inexorability. The last pages reveal a decisive, mournful countenance. Good, brisk pacing marks the Scherzo and Trio, with a solid oboe and responsive, fleet strings and tympani. The “hunting” choir of French horns resonates well. When the sonority remains a bit hollow, the sound reminds me of acoustic-process records. After having just auditioned the 1930 Mengelberg Eroica on Opus Kura, with its last movement penchant for colored variations in the last movement, I found Schillings comparatively staid and certainly more metrically conventional. Nevertheless, aside from the restrictions of the acoustic sound process, the performance has girth and stylistic conviction, and Schillings elicits fine clarity in Beethoven’s contrapuntal filigree. If not “heroically opulent” in the manner of Mengelberg, the Schillings rendition stands on its own substantial merits.

—Gary Lemco

Audiophile Audition