This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

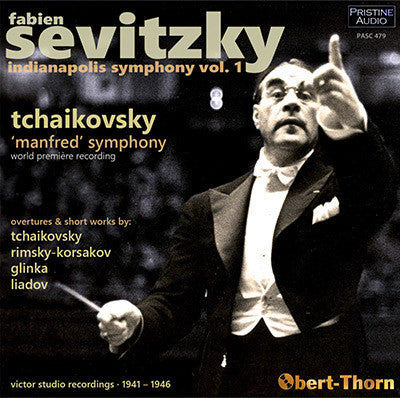

- Cover Art

Fabien Sevitzky conducts the Indianapolis Symphony

"An excellent conductor, eminently deserving of renewed attention" - Fanfare

Fabien Sevitzky was born in Vishny Volochyok, Russia on 29

September 1891 (not 1893, as other sources list). A nephew of Serge

Koussevitzky’s, his original last name was the same, but later shortened

at his uncle’s request to avoid confusion. Like him, Sevitzky took up

the double bass in order to win a conservatory scholarship. After

playing in orchestras in Russia and Poland, Sevitzky joined Stokowski’s

Philadelphia Orchestra in 1923. Two years later, he organized members

of the ensemble’s string section into the Philadelphia Chamber String

Simfonietta. (Their complete recordings have been reissued on Pristine

PASC 375.) He left the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1930, although he

continued to conduct the chamber ensemble until 1941.

Sevitzky was appointed conductor of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra in 1937, a post he held until 1955. He retired to Florida, where he became a faculty member at the University of Miami, leading the school’s orchestra and continuing to guest conduct internationally. It was during one such appearance in Athens that Sevitzky died on 3 February 1967.

Between 1941 and 1946, Sevitzky and the Indianapolis Symphony made a series of 78 rpm recordings for RCA Victor. His final recordings were made for Capitol LPs in 1953. The present program is the first in a series which aims to reissue them all, some for the first time since their initial release. None of them have ever received an “official” CD reissue.

The first two selections come from Sevitzky’s earliest Indianapolis sessions. The Russlan Overture comes on like gangbusters, showing off the exuberance and virtuosity of the ensemble and conductor in sound that was state-of-the-art for its time; and its discmate, Rimsky’s setting of the revolutionary folksong “Dubinushka”, builds to a tremendous climax. It is worth noting that Sevitzky studied under both Rimsky and Liadov at the St. Petersburg Conservatory; and in the latter’s Baba Yaga, he paints a vivid tonal characterization of the same mythical witch who inspired “The Hut on Fowl’s Legs” section of Mussorgky’s Pictures.

Sevitzky’s recording of the Tchaikovsky Manfred Symphony was the first complete version made of the work (Albert Coates had previously recorded the second movement alone), and would remain the only one until Toscanini’s 1949 recording, with a cut of some 100 bars in the finale, appeared on LP. It is dramatically paced, with much excitement in the faster sections. However, some parts are played much more slowly than we are used to. The third movement’s “Andante con moto” is here more of an “Adagio molto”; and the second movement’s trio is not “l’istesso tempo” as marked by Tchaikovsky, but something considerably slower.

Even more curious is Sevitzky’s substitution of a snare drum

(side drum) for the tambourine in the bacchanal which opens the fourth

movement. The conductor could have interpreted the “tamb.” marked in

the score as referring to a “tamburo piccolo” or snare drum. However,

the first page of the score spells out “tambourine”, so there should

have been no confusion. Its presence here remains a mysterious

precedent that no other known conductor has followed. (I am indebted to

writer Edward Johnson for pointing this out.)

The sources for the transfers were American Victor 78 rpm shellacs: late pre-war “Gold” label pressings for the Glinka and Rimsky items; postwar copies for the Liadov and Onegin Waltz; and “Silver” label wartime pressings for the Manfred. Multiple copies of the records were sourced, with the best sides from each used. Some portions of the Manfred were problematic, owing to suboptimal wartime shellac and processing.

Mark Obert-Thorn

GLINKA: Russlan and Ludmilla – Overture

Recorded 8 January 1941

Matrix No. CS 057573-2

Victor 17731

RIMSKY-KORSAKOV: Dubinushka, Op. 69

Recorded 7 January 1941

Matrix No. CS 057574-1

Victor 17731

LIADOV: Baba Yaga, Op. 56

Recorded 9 February 1945

Matrix No. D5-RC-827-1

RCA Victor 11-9247 in album M-1066

TCHAIKOVSKY: Waltz from Eugene Onegin Recorded 19 March 1946

Matrix No. D6-RC-5259-1A

RCA Victor 12-0044 in album M-1189

TCHAIKOVSKY: Manfred, Op. 58

Recorded 27-28 January 1942

Matrix Nos. CS 071331-1,

071332-1A, 071333-2, 071334-2, 071335-1, 071336-1, 071337-1, 071338-1,

071339-1A, 071340-1, 071341-1, 071342-1, 071343-1A & 071344-1

Victor 11-8331/7 in album M-940

Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra ∙ Fabien Sevitzky

All works recorded in the Murat Theatre, Indianapolis, Indiana

Reviews: Fanfare & Audiophile Audition

A real ballet tour de force in fine sound

Fabien Sevitzky (1891–1967) was a nephew of Serge Koussevitzky. He shortened his name at the behest of his famous uncle, who apparently did not relish competition from another Koussevitzky. (I have to mention, however, that when I was a kid in the 1950s and heard references to Koussevitzky on the radio, I at first thought that his last name was Sevitzky and that his first name was “Sergekou.” I had also heard of Fabien Sevitzky, so Uncle Serge’s effort to avoid “confusion” didn’t work with me.) As producer Mark Obert-Thorn recounts in his note for this release, Sevitzky, like his uncle, was a double bass player, and he played in the Philadelphia Orchestra from 1923 through 1930. After taking up conducting, he headed the Indianapolis Symphony from 1937 through 1955 and recorded with that orchestra for RCA Victor and Capitol. This release, containing performances recorded 1941–46, is the first installment in a series that is projected to reissue all of his recordings with the Indianapolis Symphony. (Pristine has already released Sevitzky’s earlier recordings with the Philadelphia Simfonietta, an ensemble he founded before his appointment to the Indianapolis position.) Obert-Thorn, rather than Pristine proprietor Andrew Rose, is responsible for the audio restorations on the present release, and there is no indication that Rose’s own techniques, XR and Ambient Stereo, have been applied. Obert-Thorn, of course, has been a renowned practitioner in the refurbishment of historical recordings for decades. His efforts here are eminently successful, and very worthwhile, since the performances on this release are uniformly excellent.

The opening pages of Glinka’s Overture to Ruslan and Liudmila, with their rapid runs, are a test for the violin section of any orchestra. Here and in the recurrence of this passage later in the piece, the Indianapolis players acquit themselves well. It helps that Sevitzky sets a less breakneck tempo than does Evgeny Mravinsky in several live performances from the 1960s. That is all for the better, for where Mravinsky sometimes sounds too frenetic, and his orchestra a bit pressed, Sevitzky’s ensemble executes these passages smoothly, maintaining poise and discipline and not seeming to scramble. (Mravinsky himself adopts a similar tempo in a 1981 performance issued by Erato.) Sevitzky’s treatment is amply energetic and kinetic, with strong rhythmic definition and precise phrasing.

Sevitzky’s tempo for Rimsky-Korsakov’s Dubinushka is less quick than that of Gerard Schwarz (Naxos), but with more powerful stresses and incisive phrasing he generates an urgent momentum, and his performance is the grander and more triumphant of the two. Evgeny Svetlanov (Warner) adopts a still more expansive tempo but shares Sevitzky’s penchant for strong accents and heightened grandeur. If forced to choose among these three performances, I would takes Sevitzky’s tightly disciplined and rhythmically incisive one, which sounds amazingly good in Obert-Thorn’s restoration of the 1941 recording.

Sevitzky’s timing for Anatoly Liadov’s miniature tone poem Baba-Yaga, depicting the fearsome witch of Russian folklore, is once again a bit longer than in the performances I have for comparison, by Svetlanov (Melodiya), Valery Gergiev (Philips), and Mikhail Pletnev (DG). (The timings are Svetlanov 3:25, Gergiev 3:12, Pletnev 3:24, Sevitzky 3:44.) None of the faster performances sound rushed, and Sevitzky’s doesn’t sound slow. Less overtly violent than Svetlanov, he generates menace by creating a sense of measured but unstoppable forward motion. The orchestra once again plays with precision and incisiveness. The sound is amazingly vivid for a recording made in 1945, although the dynamic range predictably doesn’t match that of the much later recordings cited.

Sevitzky’s 1946 account of the Waltz from Tchaikovsky’s Evgeny Onegin is a grand and celebratory one, with the strong rhythmic backbone the previous selections lead one to expect. He generates stronger tension and momentum than does Gergiev, on another Philips disc, and the orchestra plays crisply and incisively, with precise string phrasing.

The 1942 recording of Tchaikovsky’s stunningly powerful Manfred Symphony, the first ever complete commercial recording of this work, was previously reissued in Britain by the Historic Recordings label and was reviewed enthusiastically by Boyd Pomeroy in 34:3. I concur unreservedly with his favorable assessment. The balance in Sevitzky’s recording appropriately favors winds and brass, unlike that in the modern stereo recordings by Riccardo Chailly (Decca) and Vladimir Jurowski (LPO), which partly for that reason often sound too soft-edged for my taste. (Winds and brass do get their due in recordings by Riccardo Muti, on EMI, and Kurt Masur, on Warner.) Sevitzky’s firm pacing helps to unify this sprawling work. The many tempo shifts built into the piece are well integrated, and transitions are skillfully managed. The performance is at once tightly controlled and deeply felt, with sustained tension and disciplined, incisive playing from the orchestra. The opening Lento lugubre of the first movement is perfectly paced to capture the mood of deep despair. The first climax arrives as a sudden, explosive outburst. The lyrical Andante section, representing a memory of Manfred’s beloved sister and incestuous lover Astarte, is very deliberate but shaped with loving delicacy. The raging coda is taken at a comparatively quick pace and is especially violent and shattering.

In his note for this release, Obert-Thorn comments that “some parts are played much more slowly than we are used to,” specifically, the Trio section of the second movement and the Andante con moto third movement. I would add that the tempo for the scherzo is also more deliberate than usual, although it is quicker in the reprise after the Trio. I find that these tempos work. The Trio, depicting an Alpine fairy, is enchantingly lyrical, and the broader tempo imparts an especially brooding quality to the intrusion of the grim Manfred theme. The pastoral third movement starts off in a rapturous, bucolic vein, but the minor-key episode that soon intrudes has a forceful thrust, and the movement builds to an intense passion. In the finale, the opening Allegro con fuoco section (and the recurrence of this tempo later in the movement) is fast, incisive, and fiery indeed. The evocation of Astarte is once again tenderly lyrical, and the final climax, recapitulating the conclusion of the first movement, is just as raging and violent as in its original appearance. The solemn coda, reflecting Manfred’s redemption in death, is firmly paced and not too slow, celebratory rather than pompous.

On the basis of this release, Fabien Sevitzky appears to have been an excellent conductor, eminently deserving of renewed attention. In these performances he imposes tight orchestral discipline and firm tempos, but he also generates rhythmic vitality, urgent momentum, and dramatic excitement. The Indianapolis Symphony, too, long ensconced as a respected but not renowned member of the second tier of American orchestras, shows itself to have been a very fine ensemble in this era. The sound quality of Obert-Thorn’s restorations is good enough that listeners could contemplate purchasing this release simply for enjoyment of the works included, and not just for its historical value. I look forward with eager anticipation to further releases in this series.

Daniel Morrison

This article originally appeared in Issue 40:3 (Jan/Feb 2017) of Fanfare Magazine.

The restoration of the Fabien Sevitzky (nee Koussevitzky) reading of the Tchaikovsky Manfred Symphony (27-28 January 1942) at the Mural Theatre, Indianapolis by audio engineer and annotator Mark Obert-Thorn is not the first CD incarnation of this performance: it had been issued on the Historic-Recordings.co.uk label in 2009 (HRCD 00017) in a transfer by Damien Rogan. Under that aegis, the gloomy, dramatic symphony inspired by Lord Byron’s 1816 epic poem stands alone; here, Obert-Thorn adds – in the first two selections from 1941 – the earliest of the conductor’s sessions at RCA Victor. Sevitzky (1891-1967) – nephew of his more illustrious uncle Serge Koussevitzky – had studied both with Liadov and Rimsky-Korsakov in St. Petersburg, so he had imbibed the Russian style naturally. An avid collector of neckwear, Sevitzky claimed to possess the second largest assortment of neckties, after that of the actor Adolf Menjou. The boast came as part of the Indianapolis Orchestra’s appearance at Cornell University, 2 December 1940.

The Manfred Symphony (1886) evolved from the efforts of Mily Balakirev to convince Tchaikovsky that the latter could write a programmatic work after Byron without having become overwhelmed by the Berlioz influence. Tchaikovsky balked a number of times, but he finally conceded to his own imagination, which had been thwarted for two years by his own admiration of the Schumann treatment of the poem as an incidental melodrama. Typically, Tchaikovsky utilizes a series of leitmotifs to follow the course of his protagonist, who suffers an acute form of Romantic Agony. Manfred pines for his lost beloved Astarte, and the various fits of passion enjoy throes worthy of Poe as well as Byron.

Given the modern popularity of the score among such conductors as Markevitch, Maazel, Rachlin, and Louis Lane, some of Sevitzky’s tempos seem unconventional. Leonard Bernstein loathed the music, calling it “trash.” Toscanini in 1949 performed the work, even extolling its form – and then cut well over 100 bars from the last movement. The outer movements from Sevitzky unfold quite sympathetically, and the Indianapolis string tone can be elegant. The second movement Vivace con spirito – Manfred’s meeting with an Alpine fairy – moves from b minor to D Major, and its secondary theme must be counted among Tchaikovsky’s most lovely tunes, soon in counterpoint with the “Manfred” motif. The second movement received the attention of Albert Coates who, unfortunately, recorded no more of the work. Sevitzky slows down the romantic theme considerably, while the outer sections – somewhat in the “flighty” style of Mendelssohn – move briskly.

Sevitzky’s Andante con moto third movement – a G Major siciliana much in the bucolic, Berlioz style – moves at a dangerously slow pace, threatening at moments to lose the melodic thread. Still, the winds and strings preserve a redolent, spatial sensibility, quite effective. The last movement means to convey subterranean bacchantes in the presence of Astarte’s shade, and we soon hear Sevitzky’s substitution of a side drum for the composer’s designated tambourine. The fugal writing cedes more to German academics than to musically dramatic logic. The cymbal crashes prove jarring, as required. The Manichean progression from dark to light, b minor to B Major, ends with an exalted chorale, Manfred’s transfiguration. For a first complete rendition of this ambitious and ungainly score, the Sevitzky holds up well.

The other Russian items reveal an energetic, fiery personality before the music. The Glinka Russlan and Ludmilla Overture (8 January 1941) bursts forth furiously, well in the manner of Yevgeny Mravinsky, with a vibrato-rich string tone. The 1905 political-campaign song Dubinishka (7 January 1941) savors the marcato approach, militant and somber. The Indianapolis brass shines here, as well it should. The Op. 56 symphonic character-piece Baba-Yaga by Liadov revives the folk-lore witch-figure, more recently embodied in Keanu Reeves’ film John Wick. The little demon snarls, hops and skips with adequate malevolence in a resonant RCA record from 9 February 1945. Tchaikovsky’s Waltz from Eugene Onegin first impressed me when Beecham’s Royal Philharmonic played it. Then, I heard the Waltz with the vocal accompaniment in the opera, led by Mitropoulos. Here (19 March 1946), Sevitzky keeps the lithe, somewhat breathless, momentum primary, a real ballet tour de force in fine sound.

—Gary Lemco