This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

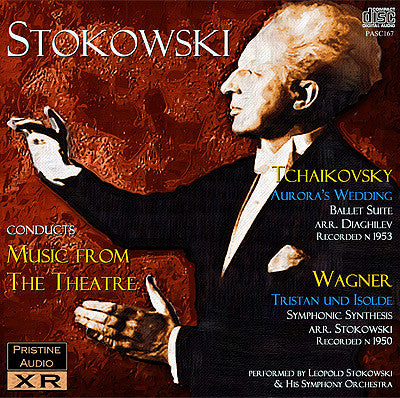

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

- Additional Notes

Two rarely-heard arrangements of famous works

Superb sound quality and fabulous playing - with Stokowski at his best

This remastering was drawn from two excellent transfers of early 1950s RCA Victor LPs. Of the two, the Wagner shows its age slightly more than the Tchaikovsky, though both have come up remarkably well.

In order to construct an accurate tonal reference for Aurora's Wedding it was necessary to attempt to 'do a Diaghilev' on a complete recording of Sleeping Beauty, and in doing so it became clear how little he actually changed the music. Aurora's Wedding is almost entirely a cut-and-paste collection of highlights from the full ballet, engineered by Diaghilev into something he could stage with his existing resources and sets - the degree to which it has been 'arranged' in the traditional musical sense is perhaps debatable: the music and scoring appears to be 99.9% Tchaikovsky, with the intervention being almost entirely confined to cutting and re-ordering.

This is not in any way to denigrate Aurora's Wedding - it is delightful and at a very digestible 40 minutes a great listen - and this XR remastering has brought out an amazing palette of orchestral colour and depth, something barely hinted at in the original LP incarnation, but always waiting to be released from the confines of those early fifties grooves.

Put together this is something like an orchestral highlights release of both of these otherwise very lengthy works. Stokowski draws on the finest musicians in New York at the time, with excellent results - the LP covers note the following:

Tchaikovsky:

First players for this recording:

|

Violin: Louis Gabowitz |

English Horn: Richard Nass Clarinet: Robert McGinnis Basson: Wlliam Polisi Horn: James Chambers Trumpet: William Vacchiano Harp: Lucille Lawrence |

Wagner:

"This performance was recorded in New York City with an orchestra that included the following instrumentalists:

W. Lincer, viola; Leonard Rose, Frank Miller, cello; Robert Bloom, oboe; Julius Baker, flute; J. De Angelius, bass; E. Brenner, W. Criss, English Horn; R. McGinnis, Clarinet; William Polisi, bassoon; J. Chambers, W. Namen, M. Fischer, J. Singer, J. Barrows, Horns; William Vacchiano, Trumpet; G. Pulis, Trombone; W. Bell, Tuba; S. Goodman, Timpani; L. Lawrence, harp."

TCHAIKOVSKY Aurora's Wedding - Ballet Suite (arr. Diaghilev from Sleeping Beauty)

WAGNER Tristan und Isolde - Symphonic Synthesis (arr. Stokowski)

Recorded 1950 & 1953

Total duration: 75:49

Leopold Stokowski and his Symphony Orchestra

Recorded 8/9 April 1953 and 17 October, 9 November 1950

Issued as RCA victor LPs LM 1774 and LM 1174

LP transfers from the collection of Edward Johnson

XR remastering by Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio, June 2009

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Leopold Stokowski

Total duration: 75:49

The Music

based on notes by Edward Johnson

Aurora's Wedding was devised by Diaghilev when a lavish 1921 London production of Tchaikovsky's complete Sleeping Beauty was a costly failure. He salvaged what he could from the production by putting together a single one-act sequence of dances taken from the ballet and called it Aurora's Wedding. It has often been performed that way in the theatre, and Stokowski first recorded it in 1953.

Stokowski was the first conductor in the USA to record a substantial selection of music from The Sleeping Beauty

(over 50 minutes of music taken from all the acts) as opposed to the

usual Suite, and he did that on RCA 78s in 1947. These were later issued

on an early RCA LP and also an HMV LP in the UK.

Then in April 1953 he recorded the Diaghilev one-act selection under it's Aurora's Wedding

title - though that didn't appear on HMV or indeed anywhere else

outside the USA. Some of the numbers are inevitably common to each

recording. The 1947 Sleeping Beauty set was reissued on Cala Records in 1998. The 1953 Aurora's Wedding

LP appeared some years ago on a Rediscovery CD, its only other release

since its LP days, and allegedly not a very good-sounding transfer.

Stokowski later re-recorded Aurora's Wedding in 1976 for Sony

and that too has come out on Cala. It is slightly more complete than the

1953 LP, which omitted one or two short numbers.

Tristan and Isolde was given the "Symphonic Synthesis" treatment by Stokowski, so that between the Prelude and Liebstod he interpolated the Liebesnacht in which the voices are transferred to solo instruments or full string sections.

Stokowski made three recordings of what is known as the "long version" of his Symphonic Synthesis of Tristan and Isolde - two Philadelphia sets in the 1930s and this 1950 LP. The sequence starts with the complete Act 1 Prelude of about 10 minutes. String temolos herald more music from Act 1 and then it moves to Acts 2 and 3 for the so-called Liebesnacht and, for the last 5 minutes or so, the Leibestod. (Stokowski also made what he called "Love Music from Acts 2 and 3" which is a sequence of about 25 minutes that omits the Act 1 Prelude entirely.)

Stokowski never recorded the complete "long version" in stereo but his two assistant conductors did: Matthias Bamert and Jose Serebrier have both recorded it.

Fanfare Review

It’s an addiction, and Stokowski was the chief pusher

In November 1921, the impresario Serge Diaghilev and his Ballets Russes presented a nearly full-length production of the Tchaikovsky-Petipa Sleeping Beauty (retitled The Sleeping Princess by Diaghilev) at the Alhambra Theater in London. As Richard Shead wrote in his history of the company, “He was taking an enormous risk, as he must have known. Neither London nor Paris had taken greatly to Giselle or Le Lac des Cygnes [“Swan Lake”]. He had accustomed audiences to barbarously sophisticated (or sophisticatedly barbarous) spectacles such as Igor, Schéhérazade, and Thamar, and to witty character ballets such as La Boutique fantasque and Le Tricorne [“The Three-Cornered Hat”]. Would they accept the pure, unadulterated classicism of Petipa? Nowadays, of course, the great 19th-century ballets provide the safest way to fill a house . . . but this was by no means the case in the early 1920s.” He also suggests that, because they had become accustomed to dancing to Leonid Massine’s choreography, some of the dancers may have even lost touch with their classical roots. The Sleeping Princess was not The Sleeping Beauty as we know it. Some numbers were cut. A few excerpts from The Nutcracker were interpolated. Some numbers were choreographed by Bronislava Nijinska. Some were reorchestrated by Stravinsky. The sets and costumes of Leon Bakst, if one may judge by illustrations, were spectacular (and expensive). Much of the audience, accustomed to clever novelties, got bored seeing the same characters on stage all evening. “Sophisticated” listeners found Tchaikovsky’s music cloying and passé. Some found the ballet to be an empty spectacle. In any event, despite the fact that the production produced a group of impassioned enthusiasts who returned night after night (and sat in the cheap seats), it got lousy reviews and bombed at the box office, by far the biggest failure of Diaghilev’s career. The presenter who had put up the money to hire the company kept the lavish sets and wouldn’t part with them unless Diaghilev came up with the money to meet his losses. Trying to salvage something from the disaster, Diaghilev (with help from someone like Stravinsky?) took about 45 minutes worth of music from the full score, juggled the sequence a bit, and arranged a one-act ballet called Aurora’s Wedding. Although it deals with the events of the last act, it uses some music from earlier ones. It was first presented in Monte Carlo, using sets from another ballet. Since it is a brilliant divertissement, it eventually took on a life of its own outside of the complete work.

Leopold Stokowski recorded extensive excerpts from The Sleeping Beauty on 78s in 1947, which found their way onto an early RCA Victor LP and, much later, to a Cala CD. He then recorded Aurora’s Wedding, or most of it, in 1953. He re-recorded it in stereo for Sony in 1976, including two numbers that were not on the 1953 recording. This, of course, doesn’t prove that the 1976 recording is complete, either, but I am sure both recordings include, at least, almost all the music. I also cannot say if the various cuts are by Diaghilev or Stokowski, and there are quite a few of them throughout. Musically, the performance, if rather fast for balletic purposes, is brilliant, featuring the superb playing and detail one is accustomed to from “his” symphony orchestra and his post-production manipulations. The CD transfer is, likewise, superb—except for the single channel, it sounds like it might have been done last year.

My first acquaintance with music from Tristan and Isolde came from Franz Waxman’s short fantasia for violin, piano, and orchestra, played in the movie Humoresque by Isaac Stern (John Garfield) and Oscar Levant with Waxman leading the orchestra. It subsequently appeared on a 10-inch LP (if you remember them, you’re old) featuring Stern playing various pieces that were heard in the movie. Later, it must have turned up in one of those multi-CD tributes to Stern that Sony issued. I have it now on a Pearl CD. It left me with a taste for orchestrated Wagner, whether authentic or not. In this corrupt state, my discovery of RCA Victor LM-1174 was a major step down the road to decadence. It was innocently titled “Music from Tristan and Isolde” and had a deceptively plain lavender and white cover. How many hours were wasted as I lounged on a couch, smoking something, and letting the erotic music wash over me? It turned out to be Stokowski’s second recording of what was called a “Symphonic Synthesis” (a term invented by Charles O’Connell, Victor’s A& R man in the 78 days) of the opera. He used themes from scenes 4 and 5 of act I, the “Liebesnacht” from act II and Tristan’s delirium from act III, framing them with the Prelude and “Love Death.” He had recorded the same arrangement in 1932, but those 78s were long gone by 1950 when the LP was recorded. Not content with inflicting this narcotic on the musical world, he did another “synthesis” with the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1935, this time including music from act II only, framing the love duet with the Prelude to act II and its abrupt conclusion, when Melot wounds Tristan. Later, he recorded the same arrangement with the All-American Orchestra, but left out the Prelude to act II and, instead of using the end of act II, he segued into the “Liebestod.” This arrangement was simply called “Love Music from acts II and III.” He retained that title when he recorded this same arrangement (restoring the act II Prelude) with the Philadelphia Orchestra in luscious stereo in 1960. If I had to use one recording to convince someone of Stokowski’s unique powers, the ones that caused Mitch Miller to refer to him as a “magic” conductor, I would choose that 1960 recording. Returning to earlier times, I was so taken with Stokowski’s 1950 “synthesis” that I actually own three copies of it (in case of LP damage). I suppose that I can now dispose of them, since this Pristine Audio CD sounds far better than any of my LPs. It’s amazingly quiet and vivid. Stokowski ravishes the music and certainly stretches the “Liebesnacht” to its limit.

Too bad he never recorded a stereo version, but happily, two of his ex-assistants, Matthias Bamert (Chandos) and José Serebrier (Naxos) have done so. Serebrier stretches the music to almost Stokowskian breadth, but brings it off successfully and, in the vein of the master, actually makes a few changes in the orchestration. Bamert is more tight-fisted in his approach (many may prefer it this way—it’s “tighter” and less sprawling), but I think that he, too, emerges with honor and both he and Serebrier use full string sections; Stokowski’s seems to be the usual cut-down one that he used with “his” symphony orchestra. You would not go wrong with any of them. Check out the couplings and decide. The Bamert and Serebrier CDs include other Stokowski Wagner transcriptions. I don’t know if they are still available, but Gerard Schwarz and Edo de Waart recorded their own Tristan takes. Schwarz’s is not a transcription, since he orchestrated nothing, and simply arranged a sequence featuring the Prelude to act I, Brangaene’s Warning, the act III Prelude, and the “Liebestod” with Alessandra Marc providing the vocals. If Stokowski’s 38 minutes isn’t enough for you, de Waart recorded a 64-minute chunk of music from the opera, using an arrangement by Henk de Vlieger. Don’t be frightened by the awful cover art—if you really want to wallow in decadent, sensuous Wagner, go for it. I own them all, plus Ormandy’s 27-minute go at the Prelude-“Liebesnacht”-“Liebestod” from 1953. What can I say? It’s an addiction, and Stokowski was the chief pusher.

James Miller