This album is included in the following sets:

This set contains the following albums:

- Producer's Note

- Full Track Listing

- Cover Art

Carl Schuricht’s late-fifties Paris Conservatoire Beethoven symphony cycle is perhaps one of the more unusual recordings both of its era and, more generally, of Beethoven cycles. To begin with there is the question of the recordings themselves.

Made in the Salle Wagram in Paris between 1957 and 1959 at a time when just about everyone was embracing the idea of stereo in classical music recordings, the Schuricht series was made and released in defiant mono. Or was it? For many years this appeared to be the case – certainly the vinyl releases at the time were all mono, and often very competitively priced – in the UK at least.

When EMI reissued the complete cycle in the late 1980s, once again the nine symphonies were released in mono. It was not until the 21st century that a stereo recording from this set emerged, in the shape of the Ninth ‘Choral’ Symphony – why this had been overlooked for so many years is hard to understand. Nevertheless the rest of the series remains mono or – in the case of these Pristine XR remasters – with a very pleasing Ambient Stereo ambience.

What was also unusual was the French orchestra, which to some contemporary ears outside of the country sounded all wrong: for some it was the playing style, for others the sound of some rather unique instruments in the brass and woodwind were off-putting. But in the fullness of time opinions have been revised and some have come around to the view that this is a very special Beethoven cycle indeed:

“My immediate impression was that I had never heard Beethoven conducted in quite this way. That is not the same as saying I had never heard Beethoven played this way. By certain string quartets, for example. I was reminded of Serkin playing the piano sonatas, even more, perhaps, of late Backhaus. The first symphony immediately created an impression of gut conviction and great vitality. As with late Backhaus, technical perfection is not an essential, phrasing can be a bit rough and breathless, but you get a sense of contact with the music that you more often get from hands-on performers than from conductors whose vision has to be realised by others: namely the orchestra. This generally translates into brisk, spinning tempi that are not driven, or goaded onward, by a conductor with a whip, but have a vitality that seems to arise from the music. In the second movement of this same symphony there is a warm songfulness rather than an attempt to wrest a prayer for humanity from every phrase. It is here, too, that the French woodwind are at their most piquant.

I must record a curious sensation over this. While it is true that the Historically Informed brigade would run a mile from such vibrato, modern performances on period-style instruments have rediscovered a factor which was still available in Paris in the 1950s. Each instrument has its own personality, makes its own contribution to the argument, instead of being blended so that the wind band might as well be a harmonium. With the wind forwardly balanced into the bargain, these performances contain elements that were scarcely heard again until the HIP movement got going two decades later.

This sense of vital contact with the music crescendos through the first three symphonies. The “Eroica” slow movement is an interesting case. Schuricht starts out at a fairly flowing, but expressive tempo. Most conductors start slower, but have to move forward later. Schuricht holds his tempo, but not in the sense of dogmatically ploughing on regardless. He simply doesn’t seem to find it necessary to make any adjustment, for his tempo fits every part of the movement beautifully. The proof of this is heard as the initial march theme returns after the climax and sails in without the conductor having to put on the brakes. The final disintegration has rarely been so moving – it emerges so inevitably from what came before. In spite of a not very slow initial tempo this is one of the longer versions on record: at 15:40 it is exceeded by Toscanini’s 16:06 in 1939 but is expansive compared with Klemperer’s 14:43 in 1956 – and no, I haven’t got these the wrong way round…

…The time has now come to take it seriously. Heaven forbid that any critic should recommend a “best version” of such multifarious works, or even a “best version” of each single symphony. We can try to distinguish between the ones that count and those that don’t. This cycle counts. It explores avenues of Beethoven interpretation, areas of Beethovenian truth, not touched upon elsewhere.” - Christopher Howell, MusicWeb International, 2013

Andrew Rose

Carl Schuricht’s late-fifties Paris Conservatoire Beethoven symphony

cycle is perhaps one of the more unusual recordings both of its era and,

more generally, of Beethoven cycles. To begin with there is the

question of the recordings themselves.

Made in the Salle Wagram

in Paris between 1957 and 1959 at a time when just about everyone was

embracing the idea of stereo in classical music recordings, the

Schuricht series was made and released in defiant mono. Or was it? For

many years this appeared to be the case – certainly the vinyl releases

at the time were all mono, and often very competitively priced – in the

UK at least.

When EMI reissued the complete cycle in the late

1980s, once again the nine symphonies were released in mono. It was not

until the 21st century that a stereo recording from this set emerged, in

the shape of the Ninth ‘Choral’ Symphony – why this had been

overlooked for so many years is hard to understand. Nevertheless the

rest of the series remains mono or – in the case of these Pristine XR

remasters – with a very pleasing Ambient Stereo ambience.

What

was also unusual was the French orchestra, which to some contemporary

ears outside of the country sounded all wrong: for some it was the

playing style, for others the sound of some rather unique instruments in

the brass and woodwind were off-putting. But in the fullness of time

opinions have been revised and some have come around to the view that

this is a very special Beethoven cycle indeed:

“My

immediate impression was that I had never heard Beethoven conducted in

quite this way. That is not the same as saying I had never heard

Beethoven played this way. By certain string quartets, for example. I

was reminded of Serkin playing the piano sonatas, even more, perhaps, of

late Backhaus. The first symphony immediately created an impression of

gut conviction and great vitality. As with late Backhaus, technical

perfection is not an essential, phrasing can be a bit rough and

breathless, but you get a sense of contact with the music that you more

often get from hands-on performers than from conductors whose vision has

to be realised by others: namely the orchestra. This generally

translates into brisk, spinning tempi that are not driven, or goaded

onward, by a conductor with a whip, but have a vitality that seems to

arise from the music. In the second movement of this same symphony there

is a warm songfulness rather than an attempt to wrest a prayer for

humanity from every phrase. It is here, too, that the French woodwind

are at their most piquant.

I must record a curious sensation over

this. While it is true that the Historically Informed brigade would run

a mile from such vibrato, modern performances on period-style

instruments have rediscovered a factor which was still available in

Paris in the 1950s. Each instrument has its own personality, makes its

own contribution to the argument, instead of being blended so that the

wind band might as well be a harmonium. With the wind forwardly balanced

into the bargain, these performances contain elements that were

scarcely heard again until the HIP movement got going two decades later.

This

sense of vital contact with the music crescendos through the first

three symphonies. The “Eroica” slow movement is an interesting case.

Schuricht starts out at a fairly flowing, but expressive tempo. Most

conductors start slower, but have to move forward later. Schuricht holds

his tempo, but not in the sense of dogmatically ploughing on

regardless. He simply doesn’t seem to find it necessary to make any

adjustment, for his tempo fits every part of the movement beautifully.

The proof of this is heard as the initial march theme returns after the

climax and sails in without the conductor having to put on the brakes.

The final disintegration has rarely been so moving – it emerges so

inevitably from what came before. In spite of a not very slow initial

tempo this is one of the longer versions on record: at 15:40 it is

exceeded by Toscanini’s 16:06 in 1939 but is expansive compared with

Klemperer’s 14:43 in 1956 – and no, I haven’t got these the wrong way

round…

…The time has now come to take it seriously. Heaven forbid

that any critic should recommend a “best version” of such multifarious

works, or even a “best version” of each single symphony. We can try to

distinguish between the ones that count and those that don’t. This cycle

counts. It explores avenues of Beethoven interpretation, areas of

Beethovenian truth, not touched upon elsewhere.” - Christopher Howell, MusicWeb International, 2013

Andrew Rose

Carl Schuricht’s late-fifties Paris Conservatoire Beethoven symphony

cycle is perhaps one of the more unusual recordings both of its era and,

more generally, of Beethoven cycles. To begin with there is the

question of the recordings themselves.

Made in the Salle Wagram

in Paris between 1957 and 1959 at a time when just about everyone was

embracing the idea of stereo in classical music recordings, the

Schuricht series was made and released in defiant mono. Or was it? For

many years this appeared to be the case – certainly the vinyl releases

at the time were all mono, and often very competitively priced – in the

UK at least.

When EMI reissued the complete cycle in the late

1980s, once again the nine symphonies were released in mono. It was not

until the 21st century that a stereo recording from this set emerged, in

the shape of the Ninth ‘Choral’ Symphony – why this had been

overlooked for so many years is hard to understand. Nevertheless the

rest of the series remains mono or – in the case of these Pristine XR

remasters – with a very pleasing Ambient Stereo ambience.

What

was also unusual was the French orchestra, which to some contemporary

ears outside of the country sounded all wrong: for some it was the

playing style, for others the sound of some rather unique instruments in

the brass and woodwind were off-putting. But in the fullness of time

opinions have been revised and some have come around to the view that

this is a very special Beethoven cycle indeed:

“My

immediate impression was that I had never heard Beethoven conducted in

quite this way. That is not the same as saying I had never heard

Beethoven played this way. By certain string quartets, for example. I

was reminded of Serkin playing the piano sonatas, even more, perhaps, of

late Backhaus. The first symphony immediately created an impression of

gut conviction and great vitality. As with late Backhaus, technical

perfection is not an essential, phrasing can be a bit rough and

breathless, but you get a sense of contact with the music that you more

often get from hands-on performers than from conductors whose vision has

to be realised by others: namely the orchestra. This generally

translates into brisk, spinning tempi that are not driven, or goaded

onward, by a conductor with a whip, but have a vitality that seems to

arise from the music. In the second movement of this same symphony there

is a warm songfulness rather than an attempt to wrest a prayer for

humanity from every phrase. It is here, too, that the French woodwind

are at their most piquant.

I must record a curious sensation over

this. While it is true that the Historically Informed brigade would run

a mile from such vibrato, modern performances on period-style

instruments have rediscovered a factor which was still available in

Paris in the 1950s. Each instrument has its own personality, makes its

own contribution to the argument, instead of being blended so that the

wind band might as well be a harmonium. With the wind forwardly balanced

into the bargain, these performances contain elements that were

scarcely heard again until the HIP movement got going two decades later.

This

sense of vital contact with the music crescendos through the first

three symphonies. The “Eroica” slow movement is an interesting case.

Schuricht starts out at a fairly flowing, but expressive tempo. Most

conductors start slower, but have to move forward later. Schuricht holds

his tempo, but not in the sense of dogmatically ploughing on

regardless. He simply doesn’t seem to find it necessary to make any

adjustment, for his tempo fits every part of the movement beautifully.

The proof of this is heard as the initial march theme returns after the

climax and sails in without the conductor having to put on the brakes.

The final disintegration has rarely been so moving – it emerges so

inevitably from what came before. In spite of a not very slow initial

tempo this is one of the longer versions on record: at 15:40 it is

exceeded by Toscanini’s 16:06 in 1939 but is expansive compared with

Klemperer’s 14:43 in 1956 – and no, I haven’t got these the wrong way

round…

…The time has now come to take it seriously. Heaven forbid

that any critic should recommend a “best version” of such multifarious

works, or even a “best version” of each single symphony. We can try to

distinguish between the ones that count and those that don’t. This cycle

counts. It explores avenues of Beethoven interpretation, areas of

Beethovenian truth, not touched upon elsewhere.”

- Christopher Howell, MusicWeb International, 2013

Andrew Rose

“My immediate impression was that I had never heard Beethoven conducted in quite this way. That is not the same as saying I had never heard Beethoven played this way. By certain string quartets, for example. I was reminded of Serkin playing the piano sonatas, even more, perhaps, of late Backhaus. The first symphony immediately created an impression of gut conviction and great vitality. As with late Backhaus, technical perfection is not an essential, phrasing can be a bit rough and breathless, but you get a sense of contact with the music that you more often get from hands-on performers than from conductors whose vision has to be realised by others: namely the orchestra. This generally translates into brisk, spinning tempi that are not driven, or goaded onward, by a conductor with a whip, but have a vitality that seems to arise from the music. In the second movement of this same symphony there is a warm songfulness rather than an attempt to wrest a prayer for humanity from every phrase. It is here, too, that the French woodwind are at their most piquant.

I must record a curious sensation over this. While it is true that the Historically Informed brigade would run a mile from such vibrato, modern performances on period-style instruments have rediscovered a factor which was still available in Paris in the 1950s. Each instrument has its own personality, makes its own contribution to the argument, instead of being blended so that the wind band might as well be a harmonium. With the wind forwardly balanced into the bargain, these performances contain elements that were scarcely heard again until the HIP movement got going two decades later.

This sense of vital contact with the music crescendos through the first three symphonies. The “Eroica” slow movement is an interesting case. Schuricht starts out at a fairly flowing, but expressive tempo. Most conductors start slower, but have to move forward later. Schuricht holds his tempo, but not in the sense of dogmatically ploughing on regardless. He simply doesn’t seem to find it necessary to make any adjustment, for his tempo fits every part of the movement beautifully. The proof of this is heard as the initial march theme returns after the climax and sails in without the conductor having to put on the brakes. The final disintegration has rarely been so moving – it emerges so inevitably from what came before. In spite of a not very slow initial tempo this is one of the longer versions on record: at 15:40 it is exceeded by Toscanini’s 16:06 in 1939 but is expansive compared with Klemperer’s 14:43 in 1956 – and no, I haven’t got these the wrong way round…

…The time has now come to take it seriously. Heaven forbid that any critic should recommend a “best version” of such multifarious works, or even a “best version” of each single symphony. We can try to distinguish between the ones that count and those that don’t. This cycle counts. It explores avenues of Beethoven interpretation, areas of Beethovenian truth, not touched upon elsewhere.”

- Christopher Howell, MusicWeb International, 2013

This fourth volume in this series - "an exceptionally fine but neglected Beethoven symphony cycle" (Fanfare magazine) includes not only the Seventh and Eighth Symphonies, given "a clarity, a vitality and an absence of traditional dogma which Schuricht could hardly have obtained except with an orchestra supposedly extraneous to the Beethoven tradition" (MusicWeb International), but also brings you the product of an interesting and unexpected discovery.

Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, recorded by Schuricht at the end of May 1958, was the only symphony to be issued in both mono and stereo versions, and whilst the second, third and fourth movements of the Ninth are taken from the same takes in both instances - the durations and performances are identical - this was not the case for the opening movement, not even remotely! If one times from the start of the opening note to the very end of the final note, Schuricht's mono take runs to 14:59, whilst his stereo version clocks in some 48 seconds longer, at 15:47 - a significant difference in pacing and approach from the conductor.

In the interests of completion we have therefore included both mono and stereo versions of the Ninth Symphony's first movement in this series. CD duration requires that the mono take is here, on the Fourth Volume as a taster for what is to come, rather than as an addendum to the fifth volume, which brings you the full, stereo version of Beethoven's Ninth, "Choral" Symphony.

Andrew Rose

Originally released in its mono version only, both in France and the UK - with a different, swifter recording of the opening movement (heard on Volume 4 of this series) - here we present the full, very wide stereo version of Schuricht's Beethoven 9, XR remastered in dramatic style. We managed to find two historic reviews of the release - first this, of the original mono LPs:

"This is a hearty performance of the 9th, in speeds alone and apart from its general conception. Put on a few bars of Klemperer conducting the first movement after hearing Schuricht and he seems an old tortoise; but what he gets out of it and the experience he makes it for the listener is plain if you go all the way with him. Schuricht’s performance does sound as if he is doing it on the B.B.C’s Home Service and must get it finished before the 9 o’clock News. [n.b. this refers to the faster, mono take]

The slow movement begins with strings that are nothing like mezza voce and when, later, they run into semiquavers, their line is most unusually emphatic. The whole movement lacks inward feeling and it utterly failed to move this listener.

As you would expect, the scherzo and finale come off far more successfully and the former is very deftly played. (The repeat of its second part is omitted, as often, and the orchestration is emended at bars 93 and 330 onwards, horns being turned over to the woodwind theme). The finale is good indeed, with an impressive team of soloists and a chorus that sings with energy and attack. And one point that immediately puts me on Schuricht’s side, the main theme is started at a real allegro right away.

But whatever one may find to commend, the conductor’s idea of the first and slow movements fails so greatly to give the experience we know this music can give that the performance as a whole cannot be recommended—and this, by the way, in spite of a very good recording indeed. And in spite, of a really first-class perfor¬mance of the 5th Symphony thrown in.

The discs are issued in H.M.V’s Concert Classics series and are very inexpensive. There is no doubt that if you care more about good sound than the expression of the music, this cheap 2-disc version is better than the 1-disc issues available. And for all I know, you may find the performance bracing!"

- T.H., The Gramophone, December 1959 (mono HMV LP release, c/w Symphony No. 5)

This second review of a stereo reissue dates from some 48 years later, when it appeared in Fanfare magazine:

"Schuricht’s interpretation is lively without usually feeling rushed, a matter of tempos on the quick side of standard, and firmly established rhythms from which he doesn’t greatly deviate. Attacks are sharp and contrapuntal lines, well-defined, notably so in the first movement. The Scherzo is especially successful, with the French horns, which simply don’t blend into the orchestral mix, making a virtue of their aggressively distinctive sound. Some other interesting touches include a rattenuto right before he cuts loose with the theme under full percussion barrage at 3:40; and a delightfully scampering trio.

The slow movement will not please those looking for “heavenly length.” I find it too lacking in atmosphere and span, given the long-breathed melodic lines that Beethoven spins so very well. The finale is similar in this respect, but Schuricht’s jaunty, incisive rhythms and quick tempos are better suited to the material. Frick’s entrance is nothing short of majestic, with his exemplary breath control, legato singing and enunciation. Dickie is slightly nasal, but there’s a nice bloom to his vibrato, and both Lipp and Höngen [sic] are strong. The Elisabeth Brasseur Chorale is splendid, and the entire effect by the conclusion is almost operatic in its joyful, maintained intensity.

The orchestra is not without obvious flaws, though. Poor blending between the sections, bad enough in itself, also means that bobbles are more obvious when they occur, and they occur more often than one could wish, despite some otherwise virtuosic playing. If there was time set aside for a touchup session on the four days in which this Ninth was recorded, it was unsuccessful in the main. Still, drive, focus, and clarity are there, in spades."

- Barry Brenesal, Fanfare magazine, Sept/Oct 2007 (Testament CD)

SCHURICHT Beethoven Symphonies, Volume One

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 1 in C major, Op. 21

1. 1st mvt. - Adagio molto - Allegro con brio (8:17)

2. 2nd mvt. - Andante cantabile con moto (6:03)

3. 3rd mvt. - Minuet. Allegro molto e vivace - Trio (3:30)

4. 4th mvt. - Finale. Adagio - Allegro molto e vivace (6:10)

Recorded 27 & 29 September, 1958

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 6 in F major, Op. 68, 'Pastoral'

5. 1st mvt. - Erwachen heiterer Empfindungen bei der Ankunft auf dem Lande (9:24)

6. 2nd mvt. - Scene am Bach (12:36)

7. 3rd mvt. - Lustiges Zusammensein der Landleute (4:57)

8. 4th mvt. - Gewitter. Sturm (3:34)

9. 5th mvt. - Hirtengesang. Frohe und dankbare Gefühle nach dem Sturm (8:39)

Recorded 30 April, 2 & 6 May, 1957

Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire

conducted by Carl Schuricht

XR Remastered by Andrew Rose

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Carl Schuricht

Recorded at Salle Wagram, Paris

Producer: Victor Olof

Engineer: Paul Vavasseur

Total duration: 63:10

SCHURICHT Beethoven Symphonies Volume Two

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 36

1. 1st mvt. - Adagio molto - Allegro con brio (10:00)

2. 2nd mvt. - Larghetto (12:06)

3.3rd mvt. - Scherzo. Allegro - Trio (3:21)

4. 4th mvt. - Allegro molto (6:57)

Recorded 26 & 27 September, 1958

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 3 in E flat major, Op. 55, 'Eroica'

5. 1st mvt. - Allegro con brio (14:15)

6. 2nd mvt. - Marcia funebre. Adagio assai (15:46)

7. 3rd mvt. - Scherzo. Allegro vivace - Trio (5:36)

8. 4th mvt. - Finale. Allegro molto (11:09)

Recorded 18, 20, 23 December, 1957

Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire

conducted by Carl Schuricht

XR Remastered by Andrew Rose

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Carl Schuricht

Recorded at Salle Wagram, Paris

Producers:

Victor Olof (Symphony 2)

Norbert Gamsohn (Symphony 3)

Engineer: Paul Vavasseur

Total duration: 79:10

SCHURICHT Beethoven Symphonies Volume Three

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 4 in B flat major, Op. 60

1. 1st mvt. - Adagio - Allegro vivace (11:44)

2. 2nd mvt. - Adagio (9:21)

3. 3rd mvt. - Allegro vivace (5:28)

4. 4th mvt. - Allegro ma non troppo (7:11)

Recorded 23, 25 & 26 September, 1958

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67

5. 1st mvt. - Allegro con brio (7:35)

6. 2nd mvt. - Allegro con moto (9:45)

7. 3rd mvt. - Scherzo. Allegro (5:12)

8. 4th mvt. - Allegro (8:34)

Recorded 25-27 & 29 April, 1957

Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire

conducted by Carl Schuricht

XR Remastered by Andrew Rose

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Carl Schuricht

Recorded at Salle Wagram, Paris

Producer: Victor Olof

Engineer: Paul Vavasseur

Total duration: 64:50

SCHURICHT Beethoven Symphonies Volume Four

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92

1. 1st mvt. - Poco sostenuto - Vivace (11:34)

2. 2nd mvt. - Allegretto (7:59)

3. 3rd mvt. - Presto (7:25)

4. 4th mvt. - Allegro con brio (7:10)

Recorded 11-12 June, 1957

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 8 in F major, Op. 93

5. 1st mvt. - Allegro vivace e con brio (9:14)

6. 2nd mvt. - Allegretto scherzando (3:52)

7. 3rd mvt. - Tempo di Menuetto (5:00)

8. 4th mvt. - Allegro vivace (8:04)

Recorded 7 & 10 May, 1957

BONUS TRACK - MONO-ONLY TAKE

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125

9. 1st mvt. - Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso (15:05)

Recorded 27-29 & 31 May, 1958

Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire

conducted by Carl Schuricht

XR Remastered by Andrew Rose

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Carl Schuricht

Recorded at Salle Wagram, Paris

Producer: Victor Olof

Engineer: Paul Vavasseur

Total duration: 75:23

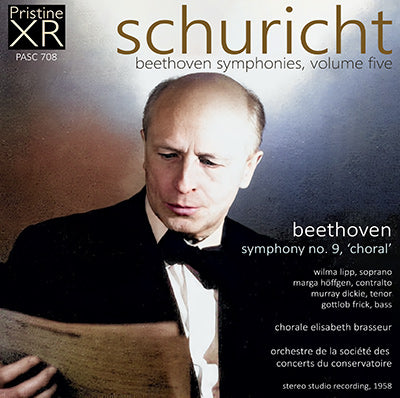

SCHURICHT Beethoven Symphonies Volume Five

BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, 'Choral'

1. 1st mvt. - Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso (15:51)

2. 2nd mvt. - Scherzo. Molto vivace - Presto (11:18)

3. 3rd mvt. - Adagio molto e cantabile (16:15)

4. 4th mvt. - Presto - Allegro (22:27)

Recorded 27-29 & 31 May, 1958

Wilma Lipp, soprano

Marga Höffgen, contralto

Murray Dickie, tenor

Gottlob Frick, bass

Chorale Elisabeth Brasseur

Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire

conducted by Carl Schuricht

XR Remastered by Andrew Rose

Cover artwork based on a photograph of Carl Schuricht

Recorded at Salle Wagram, Paris

Producer: Victor Olof

Engineer: Paul Vavasseur

Total duration: 65:51